On this 247th birthday of the United States of America, it seems an appropriate time to note the unique Americanness of football.

While Major League Baseball dominates the July 4th sports schedule, football long ago usurped baseball’s place as “America’s Pastime.” One can, and certainly others have theorized as to why football experienced a dramatic boom in popularity at the outset of the 21st Century.

But regardless the reasons behind it — access to and the ease of playing in fantasy leagues, gambling, a cheap and affordable group activity during the Great Recession, the more condescended schedule fitting into the modern life — football becoming America’s Game may have been inevitable when looking back on the sport’s history.

It’s fascinating to contrast football’s popularity domestically with the other major team sports, baseball and basketball, and how each has gained traction around the world. The popularity of baseball and basketball in other countries contributes to me deeming football uniquely American.

For as long as I’ve followed basketball, it’s been an international game. Drazen Petrovic, Šarūnas Marčiulionis and Vlade Divac were all in the NBA, and despite the Dream Team’s dominance of the Barcelona Olympics, devouring every moment of those Games that I could as a young boy engrained in me that hoops was the world’s sport.

The baseball of my youth was more nationally homogenous than basketball, but that noticeably changed by the turn of the millennium. That the best players in basketball and baseball hail from Serbia and Japan underscores the global nature of each game.

But with the transcendent talent of Shohei Ohtani taking the prominence of Japanese baseball to new heights comes another interesting point in the thoroughly Americanness of football: Japan is one of the few nations that participates in both baseball and football with organized structures comparable to the U.S.

Both baseball and football were introduced to Japan by Americans: Horace Wilson, a teacher, for baseball; and missionary Paul Rusch, for football.

Japan has professional leagues1 in both sports. And yet, baseball is a sensation in Japan; a national pastime, if you will. Football is a niche interest, a novelty.

Likewise, while conducting interviews for this piece I wrote on international recruits playing for Colonial Athletic Association football programs, a recurring theme for players from Belgium and Sweden was how rare their interest in the gridiron was among their peers.

Even in Canada, the nation other than the U.S. to most closely embrace football, the rules are different enough that it’s its own unique entity in the North.

Beyond the singularly American obsession with all things football, however, it’s a sport woven into the fabric of our history in a unique way right from the jump.

The first-ever college football game between Rutgers and Princeton included George H. Large, who went from Rutgers into a prominent political career.

As the last surviving player from the November 1869 game, Large was alive in 1932 when a future President of the United States, Richard Nixon, uh…”played” football at Whittier.

Alright, so that one’s a bit of stretch — though Nixon was famously football-obsessed. It thus makes sense that the Nixon Administration replaced Spiro Agnew as VP with Gerald Ford, a bona fide college football player and the most successful POTUS to have played the game.

I emphasize played because Woodrow Wilson is credited with coaching a national championship-winning team at Princeton.

The label coach is a bit of a stretch; professional coaches didn’t exist in the sense we know them today, a tradition established closer to the turn of the 20th Century with legends like Walter Camp and Amos Alonzo Stagg.

But in his role as secretary of the Board of Coaches, Wilson played a part in strategy and scheme important enough that one of football’s earliest, prominent historians, Parke H. Davis, credited the president with leading Princeton to the 1878 championship.

And if it’s fair to credit Wilson with coaching Princeton, it’s just as fair to deem Herbert Hoover the first athletic director at Stanford.

As something of a manager for the original Cardinal football team, the National Football Foundation cites Hoover as having spearheaded the first-ever Cal-Stanford “Big Game.”

Wilson and Hoover in the 19th Century led to the 20th Century and Theodore Roosevelt, an ardent football fan, bringing together university presidents in a move widely credited as saving the game from extinction.

Although Teddy’s actual role in preserving football is overblown depending on sources, it’s no less noteworthy that a sitting POTUS took an active hand in ensuring the sport’s existence.

With Teddy Roosevelt having saved football from extinction, it seems especially poetic that his own life was spared thanks in part to the fast actions of a football player, Elbert Martin, 1912.

During Roosevelt’s failed presidential campaign for the short-lived Bull Moose Party — an election won by Woodrow Wilson, coincidentally — gunman John Schrank shot Roosevelt from near-point blank range.

Elbert Martin, a former football player, tackled Schrank in the ensuing chaos.

That same year marked a monumental matchup in college football, pitting Jim Thorpe and the powerhouse team at Carlisle against Army West Point.

West Point’s roster included a young Dwight Eisenhower. Eisenhower’s football career didn’t last long — he was injured during the Carlisle win — but the 1912 contest does make Ike the first of an incredible five presidents from 1952 through 1980 to have had college football experience.

Eisenhower successor John F. Kennedy didn’t letter on Harvard’s varsity team, but he did play for the freshman squad. The linked piece from The Crimson quotes freshman team coach Henry Lamar as writing, “The most adept pass catcher was John Kennedy, but his lack of weight was a drawback.”

If only Harvard had fielded a sprint football team, Kennedy may have been a participant as Jimmy Carter was at Navy.

And speaking of Navy, the role the Army and Navy teams — and the military base teams established during both World War I and II — tell the stories of some of the most important moments of America’s 20th Century.

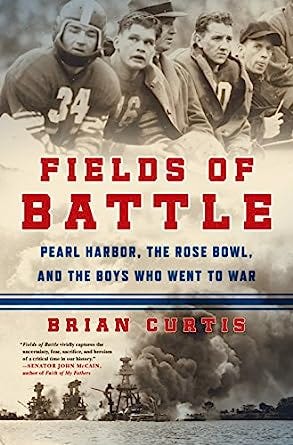

In the same vein, the 1942 Rose Bowl Game stands as one of the most illuminating examples of both the immediate fear that swept through the nation following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, and the country’s resilience.

The game between Oregon State and Duke, the only Rose Bowl played outside of Pasadena until the 2021 COVID-impacted season sent the game to the Dallas area, is a milestone moment in American history completely independent of sports.

In a sense, it’s rather fitting football never took hold outside the United States in a way comparable to our passion for the sport. The game has seeped into the very DNA of society in America in a way that can’t be manufactured.

Highly recommend the linked article via HustleBelt.com on Central Michigan University product Josh Cox’s transition to the Japanese X League.