The Greatest Days in College Football History: Richard Nixon Becomes The Gridiron Star He Always Wanted to Be

I was the only out-front, openly hostile Peace Freak; the only one wearing old Levis and a ski jacket, the only one (no, there was one other) who’d smoked grass on Nixon’s big Greyhound press bus, and certainly the only one who habitually referred to the candidate as “the Dingbat.”

So I still had to credit the bastard for having the balls to choose me — out of the fiften or twenty straight/heavy press types who’d been pleading for two or three weeks for even a five-minute interview — as the one who should share the back seat with him on this Final Ride through New Hampshire.

But there was, of course, a catch. I had to agree to talk about nothing except football.

-Hunter S. Thompson on his love of football earning him one-on-one interview time with Pres. Richard Nixon, Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ‘72

Political tensions ran high in 1969. Richard Nixon was sworn in as the 37th President of the United States in January of that year, winner of a contentious election ran against the backdrops of the Vietnam war and the Civil Rights Movement.

College campuses were epicenters of public protest to these issues, particularly during the 1969-70 academic year. May 1970 marked the nationwide Student Strike and the shooting of unarmed protestors at Kent State University.

The introductory excerpt to this article comes from Hunter Thompson’s chronicles of the presidential race two years later, but provides some illuminating context for the 1969 college football season: Richard Nixon loved him some football.

Nixon’s gridiron exploits while in office include his calling in a play to Dolphins coach Don Shula in 1971 — famously resulting in a 13-yard loss — and the hours of tapes he recorded in the Oval Office including a tirade about NFL TV blackout rules.

It’s remarkable that one of Nixon’s gripes 50 years ago remains a frustration of football fan a half-century later — and it’s a gripe on which anyone who loves the sport can agree, regardless of political stripe.

Football, in this sense, provides common ground; an avenue to set aside differences and come together for a shared passion. That Hunter S. Thompson was one of the most outspoken anti-Nixonian scribes in political press, yet piqued the president’s interest with his shared knowledge of football enough that Nixon offered up one-on-one interview time, underscores this quality of the game.

But at the same time, sports are not nor have they ever been wholly apolitical. And in the case of Richard Nixon’s love for football, what was perhaps the president’s most famous foray onto the gridiron during his tenure in the White House — which came at the culmination of the 1969 college season in a game between Arkansas and Texas — was calculated political maneuvering.

More on that in a moment. Without the events of Nov. 22, 1969, there is perhaps no presidential input made on a certain Southwest Conference game two weeks later — and thus, college football isn’t the cultural launching pad for a political movement that defined the next half-century and beyond.

The Southern Strategy

Executives at ABC took a risk before the 1969 season in setting up a December meeting between Southwest Conference counterparts Arkansas and Texas. The hope was that both might be in contention for the No. 1 ranking at season’s end, and the a ratings bonanza would ensue. The gamble paid off.

On Dec. 6, No. 1-ranked Texas beat No. 2 Arkansas in a Game of the Century that actually lived up to its billing. In some ways, the Longhorns’ 15-14 win over the Razorbacks in Fayetteville may have been The Game of the Century, ending in a two-touchdown, fourth-quarter rally.

Furthermore, it was the only No. 1 vs. No. 2 matchup in which the President of the United States determined the winner national champion in the immediate aftermath.

Given the national championship was awarded before the bowls in that era, it might not seem on its face that the football-fanatic Nixon was doing anything politically untoward in dictating the title. Maybe using his cachet as Leader of the Free to horn in — no pun intended — on Texas’ spotlight. But politically unsavory?

Well, consider the commonwealth of Pennsylvania went to Nixon’s primary challenger, Hubert Humphrey, by a healthy margin the year before. Keep that in your back pocket for a bit.

Nixon didn’t win Arkansas or Texas, either, but both states underwent electorate demographic changes commensurate with the ‘68 election that made both fertile ground to siphon off voters.

Southern states voted Democratic almost exclusively for more than a century — so much so that another football-mad president, Woodrow Wilson having grown up in Virginia despite living in New Jersey was a cornerstone of his campaign in 1912.

The Johnson administration’s championing of the Civil Rights Act, however, fractured the party’s presence in the South to such a degree that third-party candidate and “Dixiecrat” George Wallace — running on a repugnant segregationist platform — won 46 electoral votes. That includes Arkansas’ six.

Wallace was also competitive in Texas, where Humphrey edged Nixon.

Now, the Southern Strategy existed prior to Richard Nixon’s campaigns of ‘68 and ‘72 — Barry Goldwater’s 1964 campaign is credited with adopting the movement to target Southern-state voters under a states-rights platform.

However, Nixon truly embraced the Southern Strategy in a way that made the South the most reliable voting bloc to his party nationally for generations.

It’s important to note that Nixon’s camp never explicitly embraced George Wallace’s politics. Notably, after Spiro Agnew’s resignation from the vice-presidency, former star Michigan football player Gerald Ford succeeded him as Nixon’s veep, and Ford was a lifelong proponent of progressive racial politics.

Ford famously protested a 1934 game against Georgia Tech when Tech demanded Michigan bench its Black athletes, and the 38th President of the United States championed Affirmative Action later in life.

But then there’s also a litany of coincidences suggesting the Southern Strategy was adopted in a direct appeal to segregationists: the “states rights” cornerstone being touted at a time when federal intervention into Southern policy was primarily the integration of public services and schools; that another future POTUS and aggressive champion of the Southern Strategy, Ronald Reagan, is on the aforementioned Nixon Oval Office tapes going on racist tirades.

Nixon interjecting into the Arkansas-Texas game is another such coincidence.

It’s worth noting from a college football perspective that prior to the 1969 season, only Kentucky and Tennessee had integrated rosters. Auburn, Mississippi State and Florida followed suit in 1969.

Arkansas — then still a member of the Southwest Conference — also first integrated with its first scholarship player in 1969, Jon Richardson. However, with freshmen ineligible for varsity participation in this era, Richardson didn’t play for the ‘69 Razorbacks, and thus this was the last all-white Arkansas team.

The state of Texas saw noteworthy integration of its football programs throughout the 1960s, including West Texas State’s outstanding running back “Pistol” Pete Pedro and North Texas legend Abner Haynes in the early-half of the decade.

However, the Longhorns remained segregated throughout the ‘60s. Julius Whittier joined the team as a freshman in ‘69, but like Arkansas’ Richardson, wasn’t eligible until 1970.

That made the Razorbacks and Longhorns two of the last major-conference programs with segregated rosters.

A chapter in Michael Weinreb’s book A Season of Saturdays focuses on this particular fact — the racial make-up of both rosters — playing directly into the Southern Strategy, the appeal to Wallace voters, and Nixon’s media blitz around the game.

Weinreb also wrote an interesting column for Rolling Stone in 2014 that touches on the game’s political undertones.

As for Arkansas and Texas on Nov. 22 of that year, as a result of the maneuvers ABC made to move their matchup to the first weekend in December, both teams were on a bye while chaos ensued elsewhere in college football.

The Upset That Ignited A War

Reigning national champion Ohio State began the 1969 season ranked No. 1, and with good reason: Leading rushers Jim Otis and Rex Kern returned on offense while All-American defensive back Ted Provost and all-time great Jack Tatum spearheaded a defense that held opponents to 150 combined points the entire campaign.

Overseeing Ohio State’s bid for a repeat national championship and the third of his career was coach Woody Hayes.

Equal legendary and notorious, The Evansville Courier and Press described Hayes in its 1969 season preview as the “volatile football coach from Ohio State” who, at a preseason media event, “elbows his way through press row, reluctantly accepting the top billing” in the Associated Press poll.

At the same time, Hayes made comments suggesting he wasn’t all that reluctant about Ohio State being favored to win a second national championship and become the first Big Ten Conference member with consecutive undefeated seasons since Michigan in 1947 and 1948.

He pointed to his Buckeyes teams of the mid-1950s setting a standard for most consecutive conference wins among highest-division programs with 17 — a mark the 1969 Ohio State did indeed surpass. The Buckeyes won 22 straight games overall dating back to 1967 when, on Nov. 15, they pounded No. 10-ranked Purdue, 42-14.

Ohio State’s utter dominance of Purdue capped an 8-0 mark for the season, during which no opponent came within 27 points of the Buckeyes. While the 1969 campaign concluded famously with Pres. Richard Nixon awarding the national championship to Texas, Nixon could have instead handed Woody Hayes another title two weeks earlier in Ann Arbor, Michigan, with no realistic protest.

And just as presumably, Nixon would have happily done so.

Woody Hayes supported American military action in Vietnam, having done tours to U.S. installations to “go into mess halls and places like that and show movies and talk football,” he told the Columbus Dispatch in 1968.

"Those kids love sports, they're crazy about it," attested the World War II Navy lieutenant-commander. "I hope that I can do a bit to bring them up to date on football-and sports. I'm really delighted at the chance to go. I've wanted to something like this for a long time.”

What’s more, Hayes was a vehement supporter of Nixon and the two became such close friends that the former president gave the eulogy at the coach’s 1987 funeral.

Always known for his tact and his graceful public speaking, Nixon said of Hayes: “I got to know the real Woody Hayes, the man behind the media. I found that he was not the Neanderthal know-nothing that some people thought him1, but that he was a Renaissance man — a man with a great sense of history.”

Nixon never had cause to celebrate a Woody Hayes-won championship, while in office, though. Instead, on Nov. 22, 1969, Ohio State lost in what could be argued is the most famous upset in college football history.

A 7-2 Michigan team welcomed Ohio State to the Big House that Saturday, given little shot of scoring a win that would send the Wolverines to the Rose Bowl — and upend the Buckeyes’ seemingly inevitable national championship “stampede.”

In his first year as Michigan head coach, former Woody Hayes assistant Bo Schembechler led what might still be the most famous installment in the 118-chapter saga of The Game.

The Wolverines didn’t just beat undefeated Ohio State, but dominated in a 24-12 romp.

The upset is marked in the opening salvo of what’s today known as The 10-Year War, designating the series between Schembechler and Hayes before the latter retired in disgrace after punching Clemson’s Charlie Bauman during the 1978 Gator Bowl.

As shameful as Hayes’ final act as Ohio State head coach was, the significance of Michigan’s 1969 upset has a pall cast over it for much more troublesome reasons. I can’t mention the ‘69 season and Schembechler’s celebrated tenure at Michigan without noting the allegations Bo’s son, Matt, publicly shared in 2021 that his father ignored abuse by a university doctor.

Sadly, this is an unavoidable theme of the raucous conclusion to a landmark college football season.

Penn State Makes Its Case

Though Ohio State occupied No. 1 in the Associated Press Top 25 from the beginning of the season all the way until its loss to Michigan, No. 2 changed between three teams on a few occasions.

Arkansas opened the campaign there, and Texas held the post from Week 3 on, while Penn State spent a couple weeks in the second spot.

The Nittany Lions fell from No. 2, which it gained after pounding Navy and Colorado by 23 and 24 points, when it squeaked past Kansas State on the road, 17-14.

The close call in Manhattan was one of two Penn State endured early in 1969; a 15-14 defeat of Syracuse on Oct. 18 was viewed negatively enough among pollsters that the Lions plummeted to No. 8.

No opponent from that point forward came anywhere close to Penn State, which featured Franco Harris, Lydell Mitchell, Mike Reid and Charlie Pittman. The Nittany Lions concluded their regular season on Nov. 29 with a 33-8 blowout of NC State, the last in a string of five consecutive victories decided by no fewer than 20 points.

On Nov. 22, Penn State traveled to Pitt amid that run, and while the Panthers gave the Nittany Lions some trouble — the score was tied 7-7 at halftime — it turned into yet another rout.

Associated Press writer Herschel Nissenson declared in his column, “The king is dead; long live the king!” in reference to Ohio State losing and opening the door for another team to ascend to No. 1.

Penn State was one such team with a case, which Nittany Lions coach Joe Paterno made somewhat passively.

“If Ohio State hadn’t been beaten it would have been tough,” Paterno said of ascending to the national championship, per the AP. “But I think we have the credentials.”

Although the Nittany Lions were dinged in October for close wins, the finishing flourish paired well with a marquee victory earned earlier in the season: Penn State cruised past West Virginia, 20-0, between the wins at Kansas State and Syracuse.

For its part, West Virginia was a more meaningful point on Penn State’s resume than any single opponent Texas had beaten prior to facing Arkansas.

The Longhorns beat Oklahoma in that year’s Red River Shootout when the Sooners were ranked No. 8 in the nation, but the setback in Dallas began a 4-4 finish to a disappointing, 6-4 1969 for OU.

West Virginia, meanwhile, went without another blemish for the rest of the season. The Mountaineers blasted Pitt in the Backyard Brawl, 49-18; edged Kentucky in Lexington, 7-6; then on Nov. 22, visited Syracuse.

Syracuse pounced to a 10-0 halftime lead before the Mountaineers chipped away with a pair of touchdowns. The go-ahead touchdown is incredible: Syracuse tacklers greeted West Virginia quarterback Mike Sherwood, who just before impact lateraled to a streaking Jim Braxton.

Braxton then broke off a spectacular run to the end. The play is at around the 22-minute mark of the highlight reel below:

The win sealed West Virginia’s best record since 1922 and earned an invitation to the Peach Bowl, which the Mountaineers won over South Carolina to complete a 10-1 campaign.

A Once-Forgotten Unbeaten

Ohio State’s loss opened the floor for Paterno, Arkansas’ Frank Broyles and Texas’ Darrell Royal to make cases for No. 1 — though, with all three teams having games remaining, none did so with much force.

Another undefeated and untied team loomed in the poll, however, having capped a perfect regular season on Nov. 22.

Not far from Ohio State’s Columbus campus in Cincinnati, No. 20-ranked Toledo moved to 10-0 with its second shutout victory in as many weeks.

The Rockets held Xavier to 91 total yards in a 35-0 romp, putting an exclamation point on the regular season ahead of a Tangerine Bowl blowout of Davidson.

Chuck Ealey, quarterback of the 1969 Toledo Rockets, was elected into the College Football Hall of Fame just last year.

Wild Out West

College football’s other two teams entering the Nov. 22 slate undefeated — albeit both with ties on their resumes — faced head-to-head in one of the most storied installments of a heated rivalry.

The 1969 Crosstown Showdown between UCLA and USC had a lofty standard to meet, the programs just two years earlier playing in a Game of the Century. USC’s 21-20 win in ‘67 is probably the most famous matchup in the series, but ‘69 might be the most dramatic.

A fourth-down pass interference with UCLA leading 12-7 gave USC a mulligan. The subsequent Trojans touchdown reception by Sam Dickerson (who drew the pass-interference flag) is also in dispute among Bruins faithful a half-century later.

Chris Foster wrote an outstanding retrospective in 2009 for the Los Angeles Times.

Forty years before Foster’s piece, UCLA’s Danny Graham — whistled on the fateful pass interference call — told the Times “it seems like my whole life just went down the drain.”

The two-point win was USC’s third victory of less than a touchdown in 1969, a season that also included a 14-14 against rival Notre Dame.

Among the Trojans nail-biters was a 26-24 defeat of Stanford, the Cardinal’s lone loss in Pac-8 play when it welcomed Cal onto The Farm on Nov. 22.

While Richard Nixon stepped front-and-center into the college football picture in 1969, the former Senator representing California may not have been the most welcomed visitor for The Big Game with the Bay Area serving as the epicenter of political protest.

Violence at People’s Park underscored the boiling point antiwar sentiment reached in 1969, and made Berkeley a symbol of anti-Nixonian sentiment.

According to Stanford University archives, provost Richard W. Lyman criticized sit-ins of the era, but also was against the war to such an extent he directly expressed his opposition to bombing campaigns in Cambodia.

Amid a dramatically different social and political backdrop than the Arkansas-Texas game in Fayetteville, Cal and Stanford played an installment of its rivalry that ranks among the best of the 125 played since 1892.

Jim Plunkett quarterbacked the Cardinal that day and passed for 381 yards — an impressive total by 2023 standards and downright gobsmacking by 1969 — with 71 coming on a touchdown throw to Jack Lasater.

Plunkett threw a pair of touchdowns for Stanford, but was intercepted three times. Meanwhile, Cal quarterback Dave Penhall went toe-to-toe with the future Heisman winner and Hall of Famer, passing for 321 yards and touchdown and rushing for a pair of scores.

Both Penhall’s passing touchdown of 37 yards to Jim Fraser and one of his two rushing scores came in the fourth quarter. The Golden Bears quarterback may well have out-dueled the great Plunkett — if not for four fumbles committed in Cardinal territory.

Stanford won, 29-28, in one of three noteworthy Golden State games that Saturday decided by two points or fewer.

The Poets and the President

On Thanksgiving Day 1932, the 9-1 Whittier Poets completed a fourth-quarter drive against rival Redlands in which “Bill Brock, the Poets’ colored star” — as The Whitter News described it — “on the first play ran 23 yards to the Redlands 25.

“Here Glover, excellent Whittier guard, slipped over to tackle in Bob Gibbs’ place. Keith Wood at that end failed to come onto the line of scrimmage with the signal and Glover was eligible to receive a pass. He cashed in his eligibility to dashing down to the Redlands four-yard mark and there gathered one of Arrambide’s shots for a first down. On the third down Arrambide ran left tackle through a nice hole for the touchdown.”

The score proved to be the game-winner in a 13-7 decision. Whittier completed a 10-1 mark, claimed the Southern California Conference championship for the first time since 1921, and Richard Nixon had absolutely zero on-field contribution.

Still, Nixon is the best known “member” of the title-winning ‘32 Poets. I noted in this feature on California’s pivotal role in transforming football offenses that Whittier boasts an impressive history, having launched the influential coaching career of Don Coryell decades after Nixon served essentially as a scout-team player.

Whittier unfortunately shuttered its program at the conclusion of the 2022 season, another devastating blow in the slow but continuous demise of college football in greater Los Angeles.

The Poets fielded a team consistently from 1907 through last year, their competitive peak lasting from the mid-1950s through the ‘60s. Whittier won 11 conference championships from 1957 through 1969, with its last being perhaps the most improbable.

While the ‘32 Poets went into the Redlands rivalry matchup 9-1 and the conquering heavyweight, the Bulldogs were 7-1 in 1969 ahead of a meeting with 4-5 Whittier. The Poets opened the campaign 0-5, however, showing enough improvement over a late-game winning streak that the San Bernardino County Sun projected “the game rates as a toss-up.”

True to this form, Redlands and Whittier played as close to a toss-up as possible without going to a tie. Redlands quarterback Rob Selway rushed for a two-yard touchdown with 1:02 left that put the Bulldogs ahead, 14-7, and coach Frank Serrao went for a decisive two-point conversion.

It was no good, however, and Whittier instead won on a two-point conversion attempt of its own after scoring a touchdown with 13 seconds remaining.

The conference championship resulting from the 15-14 win marked an unofficial end of the Whittier dynasty, with the Poets winning just one more league title from 1970 through 1980.

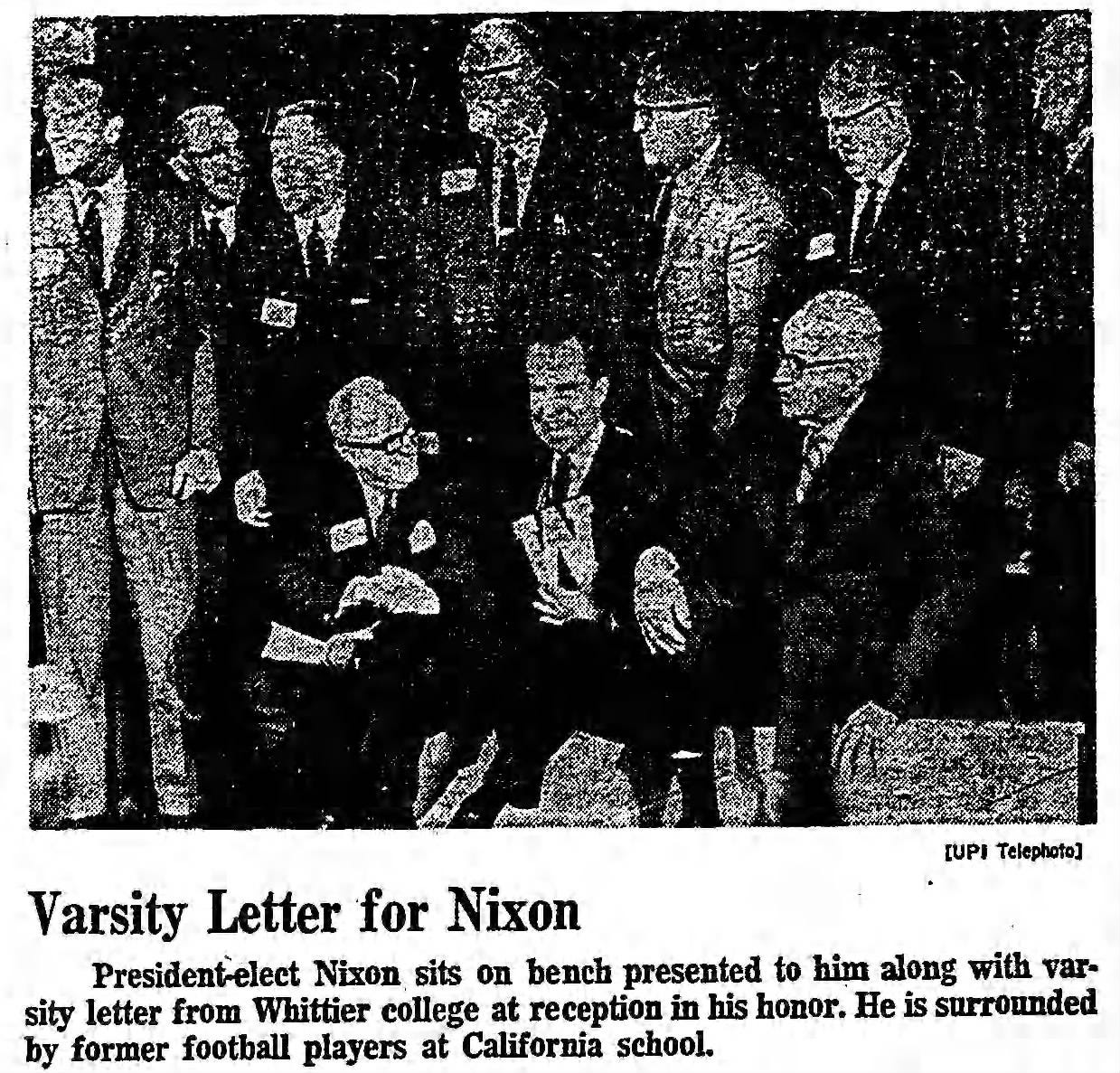

That ‘69 season was also the first in which Richard Nixon could actually be called a Whittier football letterman: The school gave him a letter upon his election to the presidency in a PR move not unlike Nixon naming the 1969 national champion.

If any of you reading this ever are asked to speak of me in any capacity, but especially at my funeral, I beg you do not say that some people thought I was a Neanderthal know-nothing.