Less than a full year before the conclusion of the 1942 college football season, America fundamentally changed. The Empire of Japan’s attack of Pearl Harbor forced the United States into growing global conflict and commencing the second World War.

In turn, all facets of American life changed — including sports.

College football continued during wartime, but with countless college-aged men enlisting, the makeup of the sport changed. Army West Point established one of the most dominant dynasties in the sport’s history during World War II, a direct result of enlistment numbers, and base teams that were every bit as good as the top university squads formed.

The War’s influence on the game became more pronounced in 1943, but the first stages of change led to a 1942 season that is one of the most chaotic in the sport’s history.

On the final, full day of the ‘42 regular season, two of today’s most prominent powerhouses claimed their first national championship; the first Heisman Trophy recipient from the SEC stood tall; a tie helped determine the Rose Bowl; and the nation’s No. 1 and No. 2-ranked teams lost by a combined 77 points.

And, sadly, one of the greatest upsets in the sport’s history was overshadowed by one of the greatest tragedies in American history.

This is Nov. 28, 1942.

Champions of the West

When Georgia and Ohio State met last New Year’s Eve in an instant classic Peach Bowl for the right to advance to the College Football Playoff Championship Game, little was made of the programs’ unique, shared history.

The 2022 season marked the 80-year anniversary of Ohio State’s first national championship — at least, if you’re a Buckeye. If you’re a Bulldog, 2022 marked the 80-year anniversary of Georgia’s first national championship.

Indeed, both programs can and do stake claim to the 1942 title. And it wouldn’t have been possible for either to do so without the events of Nov. 28.

The Buckeyes finished that day with a 9-1 record, wrapping up their campaign without a bowl game but an impressive final victory to their credit all the same.

After a Halloween loss to Western Conference1 rival Wisconsin, which dropped the Buckeyes from atop the AP Poll, Ohio State went on a November winning streak that included a 44-20 romp over 13th-ranked Illinois and a 21-7 defeat of rival and No. 4-ranked Michigan.

Beating the Wolverines on Nov. 21 propelled Ohio State from No. 5 to No. 3 in the penultimate Associated Press poll — the ideal place to be should the top two teams slip up on Thanksgiving weekend.

Ideal, anyway, if Ohio State handled its affairs against a multiple-time national title-winning coach and his outstanding Naval team.

The Buckeyes concluded their schedule on Nov. 28 at home against Iowa Pre-Flight. The one-year anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor was a little more than a week away, and the United States’ official entry into World War II drove thousands of college-aged men to enlist.

Iowa Pre-Flight was one of the military teams to emerge commensurate with the surge in enlistment.

The Seahawks 1942 roster was made up of young men enlisted in the Navy and training at the University of Iowa’s campus, with a coaching staff overseeing it that accounts for nine national championships.

Seahawks assistant coaches Bud Wilkinson and Jim Tatum won four of the nine after their tenures with Iowa Pre-Flight: Tatum in 1953 at Maryland and Wilkinson heading one of the most vaunted powerhouses in college football history at Oklahoma, where he won titles in 1950, 1955 and 1956.

Before coming to Iowa Pre-Flight, Seahawks head coach Bernie Bierman claimed five national championships — including the last two awarded before World War II changed the landscape of the sport. Bierman headed up both the repeat 1940 and 1941 champion Minnesota Golden Gophers, as well as the three-peating Minnesota teams of 1934-through-19362.

That’s all to say the service team was no pushover for Ohio State. In fact, the Associated Press deemed the assorted service teams worthy of an end-of-season poll complementing the traditional college poll. Iowa Pre-Flight was ranked No. 2 in this poll at the end of a 1942 campaign that included wins over Bierman’s former team and reigning national champion, Minnesota, and a defeat of Michigan at the Big House.

So, when the Buckeyes rolled to a 41-12 rout behind two touchdowns each from Les Horvath and Paul Sarringhaus, the outcome made an evident impression if the following Monday’s Associated Press poll is any indication.

But more on that later.

The Nov. 28 rout of Iowa Pre-Flight and the two-time reigning national championship-winning head coach completed perhaps the most significant stretch in Ohio State football history to that point, rivaling the 1920 Buckeyes’ wins over Western Conference counterparts Wisconsin, Michigan and Illinois in less than a month.

That spell of success landed Ohio State in the 1921 Rose Bowl Game. And while the Granddaddy of ‘Em All is today associated with the league we know as the Big Ten, the ‘20 Buckeyes were only the second representatives of the conference in Pasadena since Michigan played in the first edition under the Big Nine banner in 1902.

Further, the 1920 Buckeyes were the last Western/Big Ten Conference team in the Rose Bowl Game until Illinois at the conclusion of the 1946 season.

The Granddaddy instead primarily featured a team from the Pacific Coast Conference against an Eastern opponent post-World War I — and often a Southeastern team beginning with Alabama’s matchup against Washington in 1926 and resulting in Oregon State traveling to Durham, North Carolina, to face Duke in January 19423.

That means on the same November 1942 day Ohio State concluded its schedule against Iowa Pre-Flight, Southeastern Conference rivals Georgia and Georgia Tech played for an invitation to Pasadena.

The Bulldogs and The Rose Bowl

Georgia running back Frank Sinkwich rushed for 17 touchdowns in 1942 en route to a lopsided tally in the year’s Heisman Trophy voting.

But on the way to becoming the first Southern player chosen for the Heisman, Sinkwich’s most meaningful contribution to the Bulldogs’ success may have come in the locker room ahead of their Nov. 28 date against second-ranked Georgia Tech.

Writing for the Atlanta Constitution, Johnny Bradberry reported that Sinkwich called the Bulldogs together in the days leading up to Clean Old Fashioned Hate:

“‘I don’t know how you fellas feel,’ [Sinkwich] started, ‘but I personally would like to go to the Rose Bowl. We ain’t going anywhere if we lost to Tech. That’s why we are going to win. How about it?’

“The players road a mighty approval and almost smashed one another getting out the door to the practice field.”

Georgia then took to Sanford Field on the school’s Athens campus a few days later and smashed Georgia Tech, 34-0. DawgSports.com has a nice play-by-play summarizing the action.

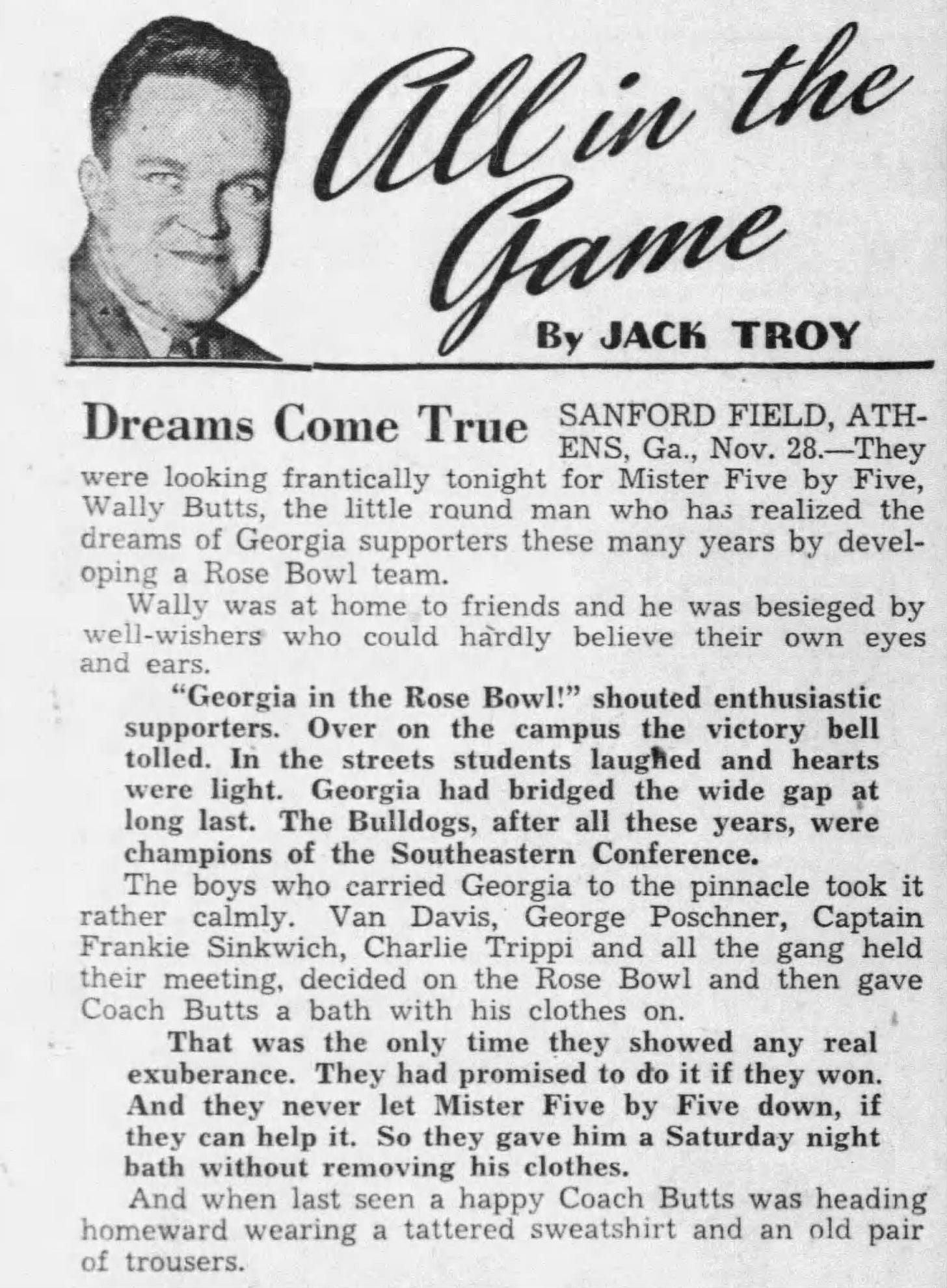

Meanwhile, from Sanford Field on that day, Jack Troy’s Atlanta Constitution column offered the following as the victorious were offered and accepted an invitation to the Rose Bowl:

January 1943 marked Georgia’s last Rose Bowl appearance until January 2018, when the Bulldogs played Oklahoma as part of the 2017 season’s College Football Playoff. I was fortunate enough to cover that game — an all-time classic — and Georgia linebacker Roquan Smith shouted out the ‘42 team specifically when talking about playing in the Granddaddy of ‘Em All.

“It's an honor just to be here … being able to play in this game and represent a lot of people [who] came before us at the university,” he said. “There are so many legends that played in this game way before us, even the Georgia team from 1942.”

Along with the Rose Bowl bid clinched on Nov. 28, the ‘42 Bulldogs would also have an argument to be named national champion.

Because the sport wasn’t founded around the idea of a national title, championships were awarded at different times. Some were bestowed before the bowls, of which there were only a handful in this era.

Media friendly to both Georgia and Ohio State commenced with the politicking, like this from the Dayton (Ohio) Herald:

And then there was poor Bill Cunningham.

A failed head coach in a winless season at SMU and player at Dartmouth when Jesse Hawley — who eventually helped revolutionize the sport as the program’s head coach — first joined the Green as an “adviser,” Cunningham gained fame as a college football columnist.

Writing for the Boston Herald, Cunningham opined Boston College was destined for both a bid to the Sugar Bowl and showdown of undefeateds with Tulsa, as well as a share of the national championship.

Jack Troy’s aforementioned Atlanta Constitution column took a quick shot at Cunningham, “who steamed up a torrid feud between B.C. and Georgia.”

“All the great work of Bill Cunningham,” wrote Troy, “was nullified.”

The Kansas City Star was considerably less charitable in its Dec. 3 edition, exhausting an entire column to mocking Cunningham’s prediction that Boston College would beat Georgia 28-0 in a hypothetical matchup.

The Star went so far as to commission a cartoon mocking Cunningham.

Nov. 28 provided plenty of fodder for sportswriters mocking Boston College’s championship bona fides, as we’ll get into. But a meeting of the Eagles against either Georgia or Ohio State was only a hypothetic; so, too, would be a Georgia-Ohio State meeting, leaving any competition for the national championship between the two for the newspapers.

As for who Georgia would actually play come New Year’s Day and the Rose Bowl, that was nearly its own controversy.

Cougin’ It In The Apple Cup

In-state rivals Washington and Washington State first played in the season-ending classic we now call the Apple Cup on Nov. 30, 1900. The teams played to a 5-5 stalemate, the first of six ties in Apple Cup history.

The sixth and final was on Nov. 28, 1942, and may have been the most consequential.

Washington State headed to Seattle ranked No. 15 in the AP Poll with a 6-1-1 overall record and 5-1 mark in the Pacific Coast Conference. The Cougars were tied atop the league’s loss column with UCLA, which still had two PCC games remaining after Thanksgiving weekend: Dec. 5 vs. Idaho, and Dec. 12 vs. rival USC.

Because of the Bruins’ unusual slate, the Rose Bowl’s invitation from the PCC wasn’t guaranteed to be offered until sometime in December. But finishing the conference season with a win over Washington would ensure Washington State would be in the running.

The Cougars played in the second-ever Rose Bowl, beating Brown in the 1916 edition, 14-0; then were on the wrong end of a shutout in 1931 against Alabama, 24-0.

A third trip to Pasadena was now in reach, evidenced in the full-page headline splashed across page 10 of the Nov. 28 morning edition of the Spokesman-Review (Spokane):

Rose Bowl Bid Hinges on W.S.C.-Washington Game in Seattle Today

The Associated Press tale-of-the-tape declared State “odds-on favorite,” but with a caveat: “Staters Face Jinx.”

“W.S.C. will be up against a Washington eleven that has shown flashes of brilliance during the season, but generally has been an up-and-down ball club. W.S.C. also will be up against a jinx that has deprived them of victory on the Washington field since 1930, when they won, 3 to 0, on their way to the Rose Bowl.”

No, misfortune in marquee spots against the rival Huskies isn’t just a modern-day phenomenon for Washington State.

“Cougin’ It” is a 21st Century meme intended to quickly summarize and invoke Washington State’s heart-wrenching losses — like in 2018 when the Cougars were on the periphery of the Playoff chase and in contention for the program’s first conference title since 2002. A snowstorm blanketed Pullman and the late Mike Leach was unable to make adjustments to overcome the weather or Jimmy Lake’s defense.

But perhaps the first instance of Cougin’ It came on Nov. 28, 1942, when Washington State outgained Washington 119 yard to 76; converted nine first downs to the Huskies’ three; and recovered a UW fumble deep in Huskies territory.

It all amounted to nothing — literally. Washington State held Washington scoreless, but failed to score in its own right, on the way to a 0-0 tie.

Two weeks later after wins over Idaho and USC, the Rose Bowl invited UCLA.

Grounded in The Bronx

College football Hall of Famer and Notre Dame Four Horsemen Jim Crowley coached a North Carolina Pre-Flight team that, in 1942, might very well have played a hand in the top ranking of both the traditional AP Poll and the AP Service Poll if not for the results of Nov. 28.

The Cloudbusters’ impact on the former was already evident going into the final full week of the 1942 regular season, with the opponent responsible for North Carolina Pre-Flight’s sole defeat occupying the No. 1 spot in the AP Poll.

That was Boston College, and the 7-6 final on Oct. 17 at Fenway Park was both the most competitive game BC played in a slate it otherwise dominated; and arguably the strongest bullet-point on the Eagles’ resume to claim a national championship.

Otherwise, North Carolina Pre-Flight was undefeated going into Thanksgiving weekend with wins over nationally ranked opponents Syracuse and William & Mary.

The Cloudbusters wrapped up in a marquee spot, visiting Yankee Stadium to play before “an expected crowd of 20,000” per the United Press.

Playing in The Bronx marked a homecoming for Crowley, who came to North Carolina Pre-Flight from Fordham. In the years prior to World War II he led the Rams to finishes of 7-0-1 and a No. 3 final AP ranking in 1937; 7-2 after a trip to the Cotton Bowl in 1940; and an 8-1 finish with a No. 6 AP ranking and Sugar Bowl defeat of Missouri in 1941.

Crowley’s Cloudbuster roster also featured a number of former Rams from the Sugar Bowl squad. The ‘42 season finale was also a homecoming for them — against a familiar foe.

The turnover at Fordham resulted in what the UP described as a “disappointing season” for the Rams. The program finished ranked in the top 20 the previous six seasons, but losses of 40-14 to Tennessee and 56-6 at Boston College in coach Earl Walsh’s first and only season as Fordham’s head coach guaranteed the streak would end.

But that didn’t mean Fordham had to close the 1942 campaign on a sour note.

From Jack Smith’s article for the New York Daily News:

“The Cloudbusters from North Carolina’s Pre-Flight School ran into something more solid than atmospheric formations at the Yankee Stadium yesterday. They collided with the steamed-up Fordham Rams who nursed an early touchdown into a 6-0 victory. Before a chilled crowd of 24,500, the Rams marched 67 yards in nine players the second time they had the ball and then kept the Pre-Flighters completely grounded except for one dangerous thrust which reached the Fordham 3.”

Steve Filipowicz — who later played both in the NFL and MLB — ran for the game’s sole score, earning the Madow Trophy4 “in the form of a $100 defense bond.”

Spoiling The Boston T-Party

North Carolina Pre-Flight very nearly shaped the title picture for 1942, but it was ultimately instead Holy Cross that carried such distinction.

Yes, a Jesuit school in Worcester, Mass., was central to the football championship landscape in ‘42, as its program visited Fenway Park for a marquee matchup with in-commonwealth counterpart Boston College.

Without Holy Cross, it’s likely neither Georgia nor Ohio State claims its first championship, as Boston College occupied the catbird seat heading into Nov. 28.

BC steadily climbed up the AP Poll that autumn with a series of dominant wins. In the five games preceding Thanksgiving weekend, the Eagles outscored opponents by a combined 195-6 margin.

Over the course of the entire season preceding Nov. 28, Boston College allowed 19 total points, including the six surrendered in its dramatic defeat of North Carolina Pre-Flight.

After shutting out Boston University on Nov. 21, 37-0, Boston College assumed No. 1 in the AP Poll on Nov. 23 thanks to Auburn’s win over Georgia.

BC had reason for cautious optimism about closing out an undefeated slate, which would presumably be enough to ensure staying atop the AP rankings.

Rival Holy Cross was 4-4-1 ahead of their visit to Fenway with losses to Dartmouth, Duquesne, Syracuse and Brown. Holy Cross, to its credit, had started to turn a corner in the final month of the season with wins over Temple and a shutout of Manhattan — but neither opponent was particularly strong; certainly not comparable to Boston College with its thoroughly dominant performance up to that point.

Still, Boston College wasn’t necessarily forecast for a rout. Newspaper columns touted both BC and HC featuring All-America potential tackles George Connor (Holy Cross) and Gil Bouley (Boston College) as offering intrigue.

And, in his nationally syndicated college football column, sports journalism luminary Grantland Rice wrote:

“Outside of the N.C. pre-flight team, Holy Cross is the one B.C. opponent physically equipped to meet Boston College on close to even terms. Holy Cross is usually poison in these annual jamborees. The odds favor Boston College, but there should be no part of an annihilation.”

The great Grantland Rice was partially correct. Holy Cross did indeed prove to be a tough match for Boston College, but the Eagles were in fact part of an annihilation.

The Crusaders won in a 55-12 romp that included Johnny Bezemes scoring one of the most unlikely touchdown trifectas possible: a 15-yard reception, a 23-yard pass and a 67-yard pick-six.

Holy Cross’ 43-point margin of victory is the most lopsided margin for a team beating a top-ranked opponent. Penn State came close to matching Holy Cross’ accomplishment 39 years later — on Nov. 28, no less — but the Nittany Lions’ incredible, 48 straight points to rout No. 1 Pitt 48-14 in 1981 still fell two possessions shy of the Crusaders’ mark.

And it was very nearly a 55-6 final, but BC scored late.

The outcome gave football fans in Athens, Georgia, and Columbus, Ohio, reason to celebrate. Boston College was left to cancel its own celebratory plans, making the upset loss an unforeseeable blessing just a few horrifying hours later.

The Cocoanut Grove Fire

Holy Cross players, coaches and supporters convened for a victory party at Parker House, which still stands today as the oldest continuously active hotel in the United States.

During the Crusaders’ celebration, Dave Anderson wrote in a 1992 New York Times article that Holy Cross running back and Hall of Famer John J. Grigas, "heard the fire engines but we didn't think anything of it."

The engines were part of the fleet called on a five-alarm fire at the Cocoanut Grove nightclub.

In Anderson’s article, Boston College’s All-American running back Mike Holovak said, “losing that game probably saved our lives.

"When we lost, our party at the Cocoanut Grove was called off."

Per the Boston Fire Historical Society, a fire that began in the club’s basement lounge — started when a busboy’s match lit to locate an electrical outlet had burned a fake palm tree — quickly raged out of control.

Boston College football players had gone their separate ways following the game — like co-captain Fred Naumetz, who the United Press wire reported had initially been feared among the victims of the blaze.

However, hundreds packed into the club and 492 were ultimately reported dead.

News brief after news brief in the days that followed reported of confirmed deaths, many of whom attended the Holy Cross-BC game. Among the survivors of the disaster was Bob Shumway, who Boston.com reported last November was one of only two known survivors of the Cocoanut Grove Fire still alive.

Shumway, Boston.com reports, was at Fenway Park for the game with a classmate.

Anderson’s Times article, meanwhile, says that a ticket stub from the football game was discovered in remaining debris three years later.

The league known today as the Big Ten Conference (despite having 16 members beginning in 2024) was the Western Conference at this time — thus Michigan’s fight song declaring the Wolverines, “Champions of the West.”

Bud Wilkinson quarterbacked Minnesota during its three straight national championship seasons of the mid-1930s.

Prior to the COVID-impacted 2020 season and the 2021 Rose Bowl Game being played in Texas to allow for a small crowd, the 1942 Rose Bowl was the only edition played outside of the Los Angeles area. This was in response to a federal moratorium on large gatherings on the West Coast in the weeks following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The Madow Trophy went to the Most Valuable Player of Fordham’s traditional year-end rivalry game against NYU. Filipowicz won the honor in the Rams’ 26-0 rout of the Violets in 1940.