Given the choice, I will almost always choose to drive from my home in California to Las Vegas rather than fly for the sake of the journey.

This has nothing to do with my appreciation for Hunter S. Thompson — in part because I have never consumed the type of mind-altering substances that prompted the renowned journalist to hallucinate seeing giant bats invade Barstow.

The actual flight from San Diego International to Harry Reid International is about an hour on the dot from gate-to-gate. The drive, meanwhile, is four hours — if one is so lucky as to avoid traffic for any prolonged stretches.

Yet, despite the potential time saved, there’s a palpable anxiety inherent with flying — and especially navigating LAS airport, which is sometimes a hellscape more terrifying than any bad trip Hunter Thompson experienced — that stands in stark contrast to the peacefulness of the drive.

It’s a journey marked with natural beauty: from the snow-capped peaks around Cajon Pass if you’re traveling at the right time of the year; to the vast expanse of uninhabited desert that rolls like dry ocean waves; and even the manmade peculiarities that could only exist in such a part of the country, like the abandoned water park that now serves as a mural for street art.

Then, driving up the gradual incline from the California-Nevada border, the Las Vegas skyline emerges from the horizon like the Emerald City of Oz.

Perhaps the Oz comparison is a double entendre; the Wizard’s Great & Powerful reputation was as fugazi as much of the glitz and allure of riches Vegas leverages to beckon in millions of visitors each year.

But Oz’s story is so much less about the destination than it is about the journey, hence the Yellow Brick Road being so much more iconic in the near-century since the film1 first wowed audiences.

Hunter S. Thompson ain’t Dorothy of Kansas, and Interstate 15 is no Yellow Brick Road. Still, as I drove that stretch leaving Las Vegas at the end of a week immersed in March college basketball, themes of their respective tales intersected as the words of Long Beach State coach Dan Monson echoed in my mind.

“My wife said that she's never had drugs in her life, but it's gotta be a similar feeling,” an emotional Monson said following his team’s 74-70 defeat of UC Davis in the Big West Conference Championship.

Certainly there’s an indescribale euphoria that comes from reaching a milestone — whether it’s earning an exclusive place in history by claiming back-to-back national championships, like UConn; advancing to a program’s first-ever Final Four, like Alabama; ending a long NCAA Tournament drought like New Mexico or even simply making the field at all, like Long Beach Beach State.

Winning can feel a drug in other ways. A taste can mutate into addiction that leaves the consumer chasing an initial high they’ll never be able to recreate.

That’s not a lament, just a statement of fact. Sports are competition, of course, so winning is the ultimate pursuit. But it is indeed a pursuit, a destination at the end of a much longer journey.

LBSU administration announced before the Big West Tournament that Monson will not return beyond this season, a decision described as a mutual parting and which I went into in my feature for The Arizona Daily Star.

The way in which Monson and Beach players discussed the move suggests otherwise.

Particulars of the decision aside, Aboubacar Traore — who, while fasting for Ramadan, recorded a triple-double in LBSU’s quarterfinal win over UC Riverside — said the Beach went into the Big West Tournament with clear motivation: Send Monson out with a conference championship and NCAA Tournament appearance.

Beach players chanted the coach’s name and cheered as Monson climbed the ladder to deliver the final snaps of the net at The Dollar Loan Center.

His tenure at Long Beach State, and perhaps his career as a head coach, ending with March Madness is an appropriate instance of life coming full circle.

March Madness catapulted Dan Monson into the basketball stratosphere 25 years ago when, as head coach of Gonzaga, he guided the West Coast Conference champion Bulldogs to the 1999 Elite Eight.

A time when Gonzaga basketball was so obscure, TV commentators frequently pronounced it “Gone-ZAW-ga” feels foreign in 2024 when the program has qualified for every NCAA Tournament since, advanced to the Sweet 16 nine consecutive years, and twice played in the National Championship Game.

It’s fair to call Gonzaga a true basketball powerhouse, which has been the case for awhile. Its staying power as a program in part explains why the Monson-coached Bulldogs’ 1999 run remains a Cinderella story still cited as quintessential March Madness.

Each of the 68 teams in every NCAA Tournament aspire for a postseason like Gonzaga’s, but the Bulldogs accomplished more than one magical run: As a program, they parlayed their One Shining Moment into a lasting identity.

Gonzaga is more the exception than the rule, of course. With being an outlier comes a shift in expectations, and simply reaching the Big Dance no longer generates a high with regards to Gonzaga.

Hell, the Bulldogs winning multiple games in the NCAA Tournament — something that was once and even still does stand as an avatar of March Madness’ unpredictability — is seemingly met with as much disdain as celebration.

That this is not an uncommon position about a Jesuit school in Spokane, which had been to exactly one NCAA Tournament before Monson’s 1999 teamfeels like a fever dream.

Maybe I really am hallucinating on some of Hunter Thompson’s secret stash.

Antagonism generates attention, though, and attention is quite literally currency at a time when fractured media struggles desperately to gain whatever audience it can in hope of survival.

I made the parallel to drug use and chasing an ever-diminishing high in my eulogy for Sports Illustrated, so it feels appropriate to mention it here in the context of the column title.

MAD Magazine, Sports Illustrated and The Importance of Physical Media

My nine-year-old son joined me on a run to our neighborhood CVS recently to pick up a prescription. While in the pharmacy line, a special edition MAD caught his eye. He didn’t know MAD nor the type of content it produced, but something about that iconic artwork — in this compilation of greatest hits, depicting Alfred E. Newman shredding copies of the ma…

Debate-driven coverage is hardly new and ascribing it to social media specifically or the internet in general is factually incorrect. The Associated Press College Football Poll was born in 1936 as a device to sell newspapers, after all.

There’s just something…meaner to it nowadays. More cynical yet less informed. Case in point, after I listened to Long Beach State’s Traore describe recording his historic triple-double amid his Ramadan observance, I remembered the time recently when an NBA talking head infamously dismissed playing elite-level basketball while fasting as “not difficult.”

I fear that in focusing only on the high that comes from winning, we in the sports community are conditioned to either not appreciate or not acknowledge the journey. It feels especially ridiculous in the context of an event as volatile as the NCAA Tournament.

Apologies for belaboring a point, as this was a central theme to a commentary last week on Purdue reaching its first Final Four since 1980.

Every Dog Has His Day: Purdue Basketball & The Rough Road to The Final Four

With all due respect to Tim Duncan, Juan Dixon, Blake Griffin, Jimmer Fredette, or even Shaq, the single consistently greatest college basketball player I ever watched through my many years following the game was Glenn Robinson. There’s a part of me that wants to chalk this belief up to childhood nostalgia. Big Dog played at Purdue during the earliest y…

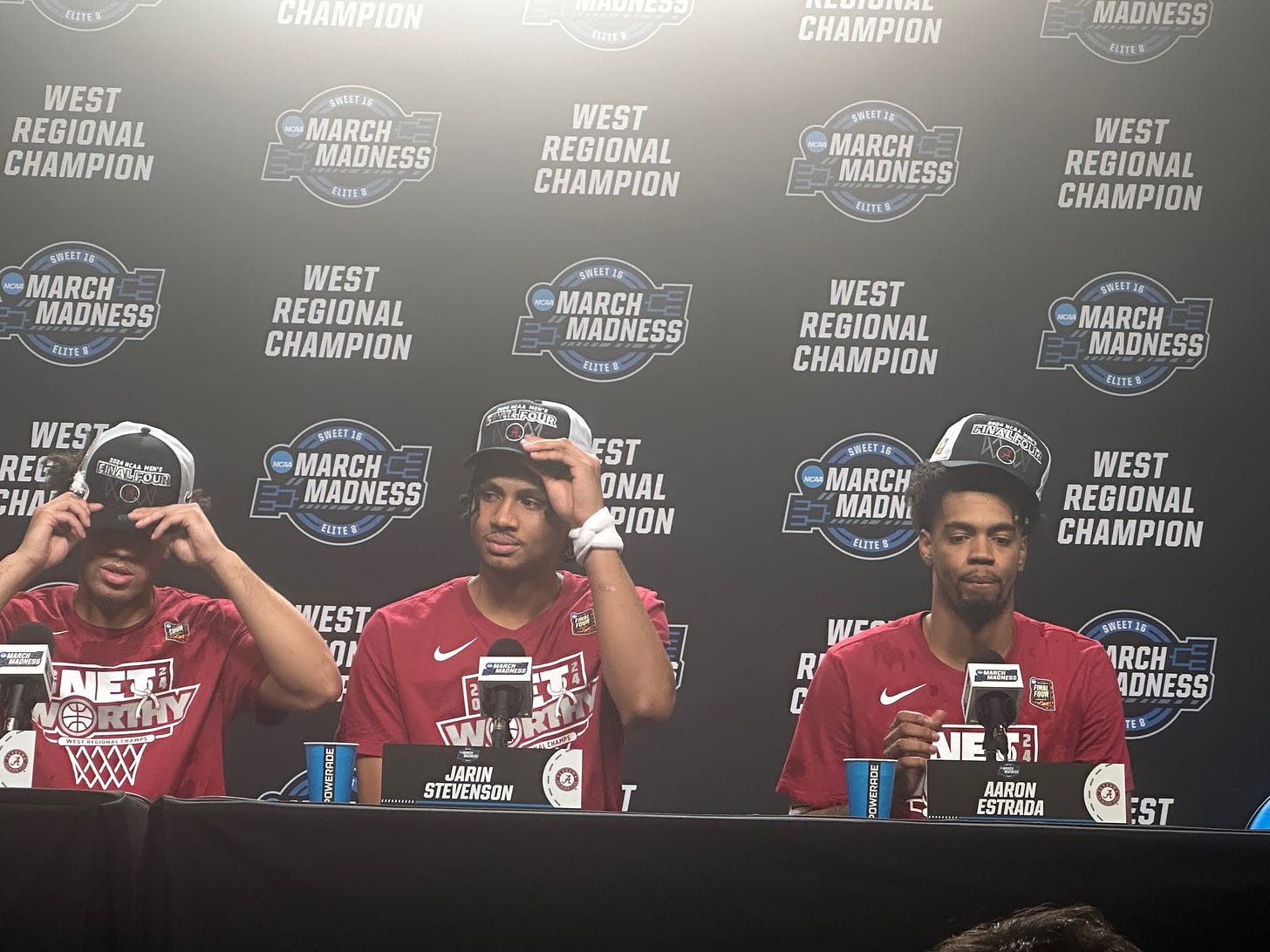

Alabama coach Nate Oats touched on it following the Crimson Tide sealing their first-ever trip to the Final Four, noting that a year prior, he had a squad expected to advance.

“The best team doesn't always win because it's a one-game elimination tournament,” Oats said following his team’s West Regional-sealing win over Clemson in Los Angeles. “You've got to be hot at the right time. And we looked like we were not hot at the right time losing, what, four of our last six going into this tournament?”

In getting to Glendale, Alabama turned to Grant Nelson in a Sweet 16 win over No. 1 seed North Carolina — the Tide in a role reversal from their Tournament exit a year prior against San Diego State.

Nelson scored just six points combined in the first two rounds, but delivered a performance for the ages against UNC.

While Mark Sears struggled to get going in the Elite Eight vs. Clemson, it was Aaron Estrada who steadied Alabama until its All-American got cooking in the second half.

The journeys that led Nelson, Estrada and Sears each to Tuscaloosa are all fascinating in their own right. Estrada had been at Oregon and Saint Peter’s before finding himself as a player at Hofstra.

Nelson came from a tiny town in North Dakota — Devil’s Lake, population 7,200 — and Sears is a local product who got a chance to elevate his home-state basketball program.

The 2024 NCAA Tournament is unique in that the National Championship Game featured what were pretty clearly the two best teams in the country throughout the season.

Purdue may have fallen short against a uniquely excellent UConn team, but I hope that Zach Edey’s journey to the title game is remembered for being as remarkable as it really was . Even in defeat, he scored 37 points and grabbed 10 rebounds in one of the most individually productive Championship Games of modern times.

And his incredible March is just a fraction of the longer journey, from an awkward freshman coming off the bench who transformed into a two-time Naismith Award winner and one of the best college centers ever.

Yeah, everyone wants to feel that sensation that comes with winning; that intoxicating adrenaline rush. But it should never overshadow the path taken to get there.

Whether the Yellow Brick Road, I-15 through Bat Country or the Road to the Final Four, the journey is the real story.

The beloved 1939 movie starring Judy Garland was an adaption of a popular novel, and not the first cinematic interpretation of the book. The silent film-era Wizard of Oz is terrible, however. And, the book — widely considered a Gilded Age political allegory — is not as ingrained in the zeitgeist.

I just want to figure out how you're making the drive from San Diego to Vegas in 4 hours...🤔