With all due respect to Tim Duncan, Juan Dixon, Blake Griffin, Jimmer Fredette, or even Shaq, the single consistently greatest college basketball player I ever watched through my many years following the game was Glenn Robinson.

There’s a part of me that wants to chalk this belief up to childhood nostalgia. Big Dog played at Purdue during the earliest years I have vivid memories of actually carving out watching games every night on ESPN and having a real understanding of what I was seeing.

But, with the benefit of statistical backing, I can write confidently 30 years later that Glenn Robinson was the best college player in that time.

With 30.3 points per game in 1993-94, he was the last scorer to average 30 a night until Marcus Keene posted exactly 30 per for Central Michigan in 2016-17. And while Keene attempted nearly 11 3-pointers per game for a Chippewas team that finished 16-16, Robinson put up his numbers with a multifaceted repertoire as the pillar for a top-seeded, Big Ten championship-winning Boilermakers squad.

Robinson also averaged more than 10 rebounds and nearly two steals per game on his way to a variety of National Player of the Year awards.

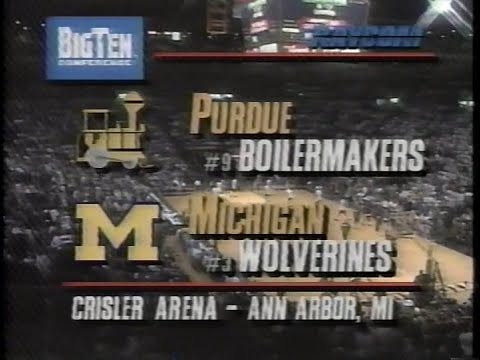

A road win in a top 10 showdown at Michigan late that season ranks among the most impressive individual performances of modern times. Robinson dropped 37 points, 10 in the final five minutes including the game-winner, in an instant classic opposite Jalen Rose, Juwan Howard, and the rest of a Wolverines team that nearly reached a third consecutive Final Four.

The Fab Four-Minus-One lost in the Elite Eight to eventual national champion Arkansas. Perhaps Purdue would have met a similar fate had it run up against the Razorbacks; the 1993-94 season marked the culmination of several years of steadily progressing excellence under coach Nolan Richardson.

A National Championship Game pitting Arkansas star forward Corliss Williamson against Purdue’s Glenn Robinson may have been a blast. Topping the National Championship Game we actually got in 1994 would have been a tall order, however, as Arkansas instead outlasted Duke in an all-timer.

Duke advanced to its fourth title game in five years thanks to an Elite Eight victory over Glenn Robinson and Purdue. The pairing was the stuff of March Madness marketing dreams, featuring two bona fide stars with a bevy of storylines at play — not the least of which was Purdue coach Gene Keady seeking his first trip to the Final Four.

This is a matchup that even decades later leaves me with conflicted emotions, as the Blue Devils were pretty well-established heels by this point.

However, the adolescent fandom of Grant Hill that prompted me to own his original, rookie-year Pistons jersey; the hideous teal update released his third season; his Dream Team ‘96 jersey; and the first two generations of his signature Fila sneakers was already in full swing.

In fact, Grant Hill became one of the first basketball players I remember enjoying back in his freshman season at Duke. His iconic dunk in the 1991 National Championship Game stands out among my earliest basketball memories.

So while I surely got some youthful excitement out of Grant Hill out-dueling Glenn Robinson in a showdown of 1st Team All-Americans, their Elite Eight matchup is not the farewell to college basketball an all-time great like Big Dog deserved.

Robinson recorded a double-double, yes. But his 13 points were less than half his season average, and he shot a woeful 6-of-22 from the floor and 0-of-6 from 3-point range.

Interestingly enough, though, this wasn’t exactly a legacy-making performance for Grant Hill, either. He scored only 11 points shooting 3-of-11 from the floor and committing a team-high four turnovers.

The only player on the court that day with more turnovers was Robinson with six.

Hill rebounded with 25 points in the Final Four win over Florida, and posted a pretty remarkable stat line in the National Championship Game with 12 points, 14 rebounds, six assists, three steals and three blocks.

Hill also committed nine turnovers against Arkansas.

I mention that not as a slight on Hill, whose all-around performance against Arkansas was outstanding. The title tilt would not have come down to Scotty Thurman’s late-game jumper without Hill’s impact for Duke — nor would the Blue Devils have even been there in Charlotte without the All-American forward.

Rather, it’s important to understand there’s complexity to when, how, where, why a team, player or coach’s NCAA Tournament ends.

The sports media content we consume in this era demands that we evaluate greatness through a wholly black-and-white lens. If one’s measure of excellence is determined exclusively by winning championships, or reaching an arbitrary point1 of the postseason bracket, they are missing an awful lot to appreciate.

I thought about this concept as I was writing this story from the Sweet 16 for the Arizona Daily Star. Our current culture of determining success only through championships — or in the case of college basketball, Final Fours — is especially reductive when applied to a sport where a single game that can vary wildly dictates teams’ fates.

Purdue’s first Final Four team of the modern March Madness era is an especially interesting case study into sports-media reductivism.

In an era when stars not staying in college is a regular lament, Zach Edey becoming the first repeat Naismith Award winner since Ralph Sampson never really felt like a topic appreciated with the magnitude of the accomplishment.

I suspect that changes with Edey leading Purdue to the Final Four. But had Edey produced the exact same kind of performance he delivered in the Elite Eight win over Tennessee — 40 points, 16 rebounds — and the Boilermakers lose, is Edey’s impact on the game any less meaningful?

Hell, even while Edey was dominating during one of the most impressive March Madness runs of my time following the sport, I somehow still see reductive nonsense about Edey.

Most notably, Purdue coach Matt Painter was asked at a press conference about critics who dismiss Edey as not good, just tall. While the question makes me cringe, because the premise is so faulty as to not deserve conversation, I’m glad it was asked for the answer it elicited from Painter.

Social media…you know what? It’s call it what it is: The platform formerly known as Twitter has been bad for journalism.

It would be as reductive of me as the mindset I’m decrying here to not mention the platform has its positives — plenty of them! — but I strongly believe it’s been more pervasive than beneficial.

I will spare the tedium of listing the myriad reasons I chose to stop using the app, nor will I write a self-indulgent diary explaining all I learned about myself since quitting several weeks ago.

Matt Painter’s response to a patently stupid mindset that a simplistic hot-take culture, exacerbated by an especially moronic megaphone, fostered summarizes my takeaways more effectively than I could hope to.

As far as Edey powering Purdue to the Final Four, it’s noteworthy that his impending back-to-back Naismith selections match a feat that happened more recently than a Boilermakers team making the national semifinals.

When a program that had the best player of a generation in Glenn Robinson, a Hall of Fame coach in Gene Keady, and plenty of outstanding teams under Painter’s direction before 2024 that all lost earlier in the Tournament, the primary takeaway with regard to Purdue basketball should be this:

It’s really, really freakin’ hard to reach the Final Four.

A friend of mine once noted to me how much differently various coaches and programs would be perceived if the Div. I NCAA Tournament chose the Elite Eight for its premier part of the bracket, which is the case in Div. II, instead of the Final Four.