Driving southwest on Interstate 15 as I left Las Vegas following a week of college basketball tournaments, I noticed a billboard approaching The M on the city’s outskirts with the phrase, “Make UNLV Basketball 1990 Again.”

The cringiness of invoking an especially divisive campaign slogan from almost a decade ago notwithstanding, the general sentiment aligns with a few positions I have shared on The Press Break:

Las Vegas is a basketball-crazy city.

Las Vegas: Basketball Town

LAS VEGAS — Asked about the NCAA Tournament’s first-ever venture into Las Vegas on Wednesday, UCLA head coach Mick Cronin smirked. “Long overdue,” he said. Basketball has a long and storied tradition in Las Vegas that truly began to manifest a half-century or so ago. In the 1970s, Jerry Tarkanian’s departure from Long Beach State up the 15 to UNLV trans…

Jerry Tarkanian’s Runnin’ Rebels are fondly remembered decades later not just because they won or for how they won — though the latter doesn’t hurt — but for representing something culturally transcendent.

That the Tark era peaked in the early 1990s, coinciding with the explosion of the West Coast hip-hop scene, gives UNLV basketball resonance today that parallels the rise of Dr. Dre, Eazy E, Snoop Dogg, Ice Cube.

While Ice Cube apparently hooped well enough in his heyday to record triple-doubles in pick-up games, Snoop was apparently the West Coast rapper best-equipped to run with the Rebels.

And, in fact, Snoop (real name Calvin Broadus) said in a 1993 SPIN interview that Tarkanian recruited Broadus to UNLV around the time Snoop recorded his debut on Dr. Dre’s title track for the 1992 film Deep Cover.

Tarkanian debunked the claim not long after, but Snoop choosing UNLV with which to associate his rising-star persona aligns with the theory the Runnin’ Rebels were basketball’s parallel to Miami football of the same era.

From The Archives: "Whammy in Miami," The Rise and Fall of Miami Hurricanes Football

The following originally appeared on Patreon in July 2020. _________ In sports, as in life, nothing lasts forever. Still, inevitable conclusions are no less shocking when that bell tolls — from Michael Jordan's walk-off jumper to cap the Bulls dynasty, to Tom Brady's pick-six thrown against Tennessee that signaled an end to his role spearheading arguably…

But what if UNLV football had been the UNLV basketball of the gridiron? In some ways, Rebels football under the Big West Conference banner showed the potential to evolve into something bigger than the program’s ever been.

The Knap Era

Tony Knap served as head coach for three programs that played in the Big West at various times, though Knap himself never toiled in the league.

He spent time as both an assistant and as head coach of Utah State in a tenure notable for his recruitment of the greatest player in program history, Merlin Olsen.

Knap came to Boise State in 1968, guiding its football transition to four-year college competition after having previously been a junior college; then in 1970, overseeing BSU in the move from NAIA to NCAA membership.

His next move came in 1976, when he took over at UNLV.

Knap’s first two seasons at UNLV coincided with its final at the Div. II level, during which the Rebels went 9-3 and 9-2. At UNLV, Knap was again tabbed to guide an important transition when in 1978, the school’s athletic department made the move to Div. I.

“Our goal for this coming season is to average 400 yards and 21 points a game,” Knap told The Daily Spectrum in Utah ahead of the 1978 campaign. “We met that goal in 1977 and we expect to meet it again this year, despite the great increase in resistance we will be facing from our opponents.”

UNLV fell short of its 400-yard per game offensive goal, posting a little more than 383 a contest. However, the Rebels averaged 22.6 points per game — which, in that era, was good for 41st in the nation.

UNLV employed a multifaceted rushing attack in ‘78, with Leon Walker, Russell Ellis, Michael Morton and Bobby Batton scoring from five to nine rushing touchdowns and averaging between 30 and 90 yards per game.

The Rebels offense also featured Henry Vereen, nicknamed “Vroom,” for his breakaway speed in space. Knap and his staff utilized Vereen’s explosive playmaking as a pass-catcher out of the backfield and on special teams.

His son, Shane Vereen, thrived in a similar capacity for Cal and later in the NFL with the New England Patriots.

The Rebels’ scoring production jumped more than eight points per game in 1979 to a shade less than 31 a contest, 10th in the nation; and another four points in 1980 to 34.9, good for third nationally.

It may not have been quite the football equivalent of Tark’s high-scoring basketball offenses, but the grid Rebels were ahead of the curve.

Making their offensive prowess in the Knap era all the more remarkable, the Rebels shifted from a run-based attack in 1978 to employing one of the most productive passing schemes in the game by 1981.

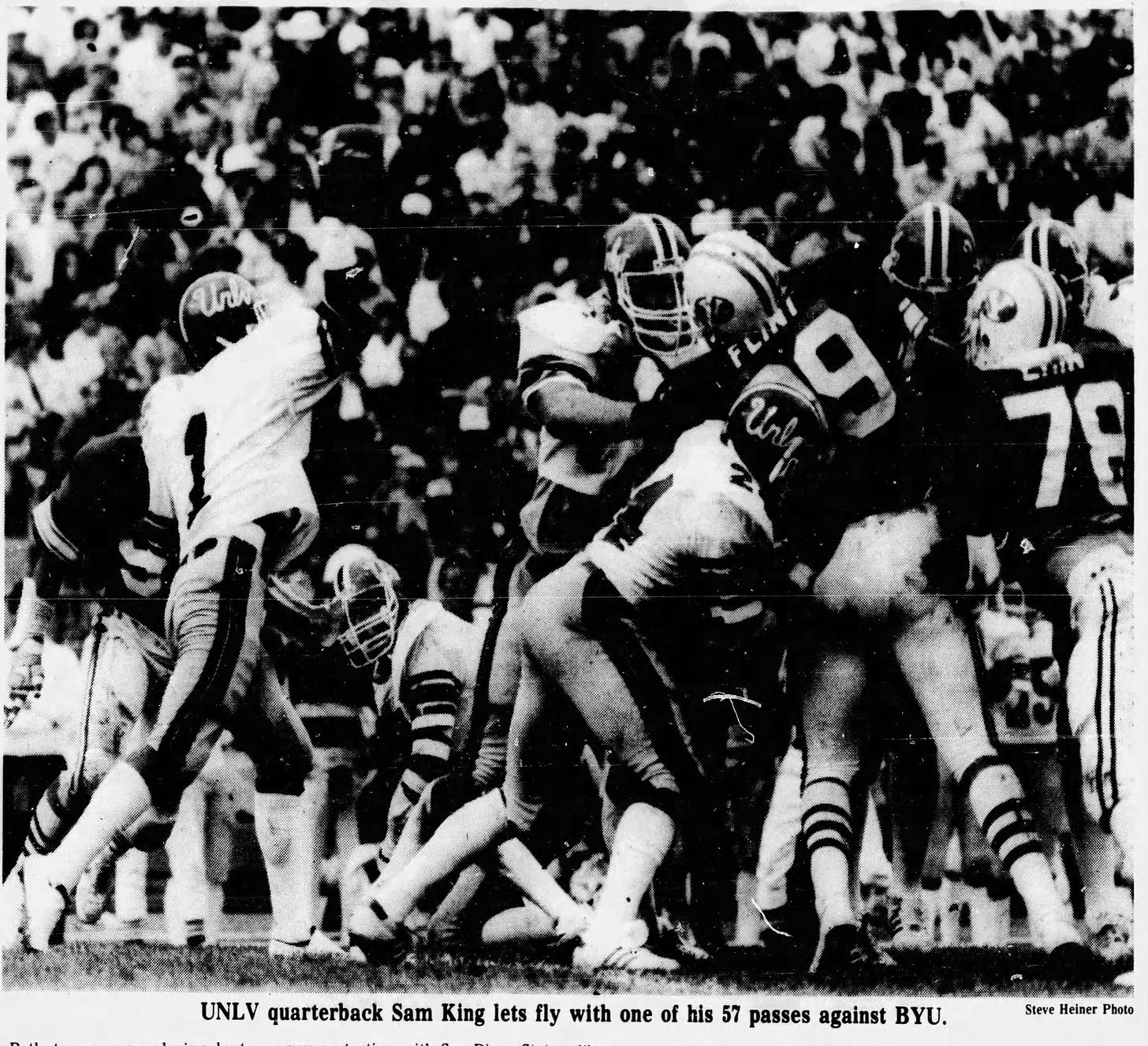

With as much as quarterback Sam King put the ball in the air, another personality who arrived on the Las Vegas scene around the same time as Tony Knap with a similar name — journalist George Knapp1 — would have found plenty of Unidentified Flying Objects zipping around the Silver Bowl.

King’s 433 pass attempts were second-most in the nation that season. His 3,778 yards led Div. I, outpacing the next-most productive passer by more than 200 yards.

No. 2 was Jim McMahon, operating in LaVell Edwards’ offense.

With quarterbacks like McMahon, Steve Young and Ty Detmer putting up eye-popping numbers, Edwards became known as one of the forefathers of the modern passing game — and deservedly so. But on an October day in 1981, Edwards and BYU were bested in their own style of game by a UNLV team with an offensive coordinator who achieved his ultimate coaching success in basketball.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Press Break to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.