The following originally appeared on Patreon in July 2020.

_________

In sports, as in life, nothing lasts forever. Still, inevitable conclusions are no less shocking when that bell tolls — from Michael Jordan's walk-off jumper to cap the Bulls dynasty, to Tom Brady's pick-six thrown against Tennessee that signaled an end to his role spearheading arguably the most dominant franchise in NFL history.

Miami's 38-20 loss to Washington in September 1994 was no different. The Hurricanes were destined to lose at the Orange Bowl sometime, surviving a handful of close calls before the appropriately named Whammy in Miami.

And yet, The U exuded such an air of invincibility that the end of college football's longest-ever home-field winning streak felt almost impossible.

"It's something I've never seen and never thought I would see," Miami wide receiver Chris Jones told the Palm Beach Post in the aftermath. "An opposing team celebrating on our field."

Although the Hurricanes last lost in the Orange Bowl to open the 1985 campaign, our story goes back further.

THE CULTURAL IMPACT OF THE U

Various sports programs and franchises in the 1980s and early 1990s transcended their mediums through the rise of cable television. Certainly greater accessibility to audiences helped, but a teenager with a passing interest in football could turn on MTV and see Eazy E sporting a Raiders cap in an NWA music video.

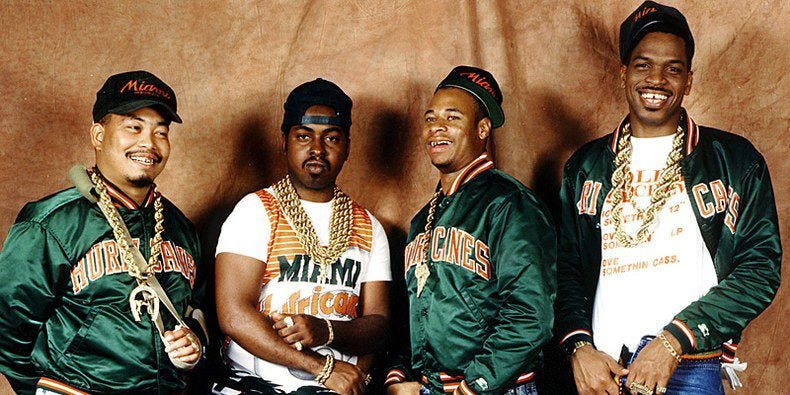

In this regard, teams including the L.A. Raiders of the NFL, and UNLV Runnin' Rebels and Fab Five Michigan Wolverines of college basketball grew into cultural touchstones. One could reasonably argue Miami football laid the foundation.

Through their competitive style, their fashion, their demeanor, these teams represented the attitudes of American youth — in particular, Black Americans. While it stands to reason that rosters made up largely of young, Black men would reflect such an identity, this was well outside of the mainstream norm.

In a sport with a very militaristic ethos to it, Miami's embrace of exuberant celebrations and the hip-hop culture with affiliations like that with 2 Live Crew founder Luther Campbell made The U counterculture.

Now, it's worth noting Miami football's rise came only a generation after the Civil Rights Movement, of which the city of Miami itself was a heated epicenter. Even the Orange Bowl specifically had its own sordid and racist history.

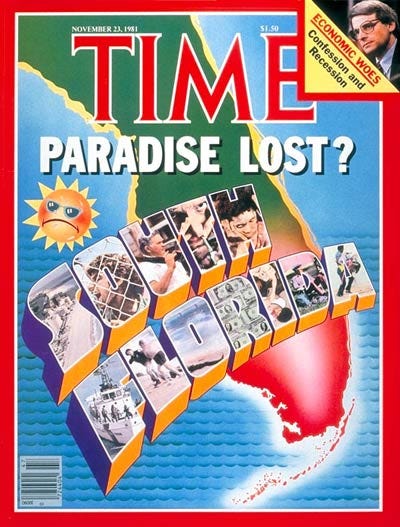

Meanwhile, the program's swagger-filled ascent coincided with the city's surging cocaine wars. TIME published an in-depth cover story in November 1981 entitled "Paradise Lost." Twenty-five months later, The U won its first national championship.

That filmmaker Billy Corben directed both Cocaine Cowboys and the ESPN 30 For 30 documentary The U is poetic. Both films detail stories in parallel timelines, and do so while weaving in important cultural realities from the Miami of the time.

In the case of Hurricanes football, it was a dynasty built through players recruited from South Florida's Black communities. From a 2010 ESPN feature on the program's local roots:

"The neighbor kids would see their local heroes on television and then in the NFL and they wanted to follow them," said Larry Blustein, a lifelong Miami-area resident and Florida recruiting analyst. "They were successful; they had that sort of neighborhood swagger that the inner-city kids could relate to."

The blueprint began with Howard Schnellenberger.

BUILDING THE U

Hired in 1979 — and replacing Lou Saban, a remarkably relevant name at the time of this publication — Miami was a mere 12 years removed from desegregation. My research for this retrospective did not yield much on Schnellenberger purposefully emphasizing recruiting predominently Black high schools for anything other than pragmatic goals, but no matter if one was a byproduct of another, he accomplished in his main objective.

From the above ESPN story:

"Coach Schnellenberger was very direct and honest, he wanted to build a powerhouse," [Alonzo] Highsmith said. "He wanted to build a powerhouse with the local players."

Schnellenberger's plan to build a powerhouse was evident from the jump, at least in the reaction of Hurricanes upon his hire.

"I can't wait to start practice," tight end Mark Cooper told the Miami Herald in the Jan. 9, 1979 edition. "I've heard a lot of good things about him. He's one of the best offensive coordinators in the nation. When I read he was the leading candidate, I was hoping he'd take the job."

From the same Herald story, then-freshman quarterback Mark Richt expressed what might be interpreted as trepidation — though the future Georgia Bulldogs and Miami head coach's fears were quickly assuaged.

"I'll be real happy if he uses the pro offensive [scheme]," Richt said. "If the veer is through at Miami, I'll be the happiest of all."

The former Miami Dolphins offensive coordinator Schnellenberger did indeed abandon the veer, implementing a scheme that emphasized the pass more with each season. In 1978 under Saban, the Hurricanes attempted 204 passes as a team; in '79, that figure climbed to 306. By '83, Bernie Kosar attempted 327 passes.

The revamped offense played a critical role in Miami's ascent, and remained a program hallmark throughout the 1980s after Schnellenberger's departure. When Vinny Testaverde won the 1986 Heisman Trophy, he completed 63.4 percent of his 276 attempts for 26 touchdowns.

With the more modern offense came wins, and with wins came The U's signature swagger. As the program's profile elevated came inevitable backlash, an inevitability of winning — but with poorly disguised cultural undertones.

FEAR OF A BLACK HAT

College football's reluctance to desegregate in Southern states like Florida made it one of the last official institutional vestiges of Jim Crow. Although the protests stopped and the Civil Rights Act ushered in some needed changes, racial strife bubbled beneath the idyllic facade that was the 1980s.

Ronald Reagan won a resounding reelection in 1984, less than a full year after Miami's national championship, campaigning on the promise of Morning in America. Reagan ushered in the decade, however, pushing a racially charged anecdote of a "Welfare Queen."

He expressed loud opposition to the landmark Regents of the University of California v. Bakke decision of 1978 that laid the groundwork for Affirmative Action. It's no coincidence that Republican predecessor Gerald Ford, a lifelong advocate for racial equality, was a staunch proponent of Affirmative Action and Reagan was against it.

The latter called back to the Southern Strategy, a Nixonian appeal to the exodus of Dixiecrats during the Civil Rights Movement; Reagan so aggressively embraced the Southern Strategy that one of his pivotal campaign moments came at a speech on states right given tactically in Mississippi. Below is an excerpt just ahead of the 1980 election via the Greenwood (Miss.) Commonwealth.

That's not to dismiss Reagan's nod to the Southern Strategy as purely political, though: His own playbook as governor of California called for fear-mongering of the Black Panther movement in Oakland to curry support among the state's White population.

So while America embraced a veneer of unity in the 1980s, the AIDS epidemic ripped through cities; crack ravaged communities and a more aggressive approach to Nixon's War on Drugs disproportionately targeted Black people.

All that is to say racism from the Jim Crow era didn't just disappear; it became less overt. Likewise in sports, the rise of sports teams that were unapologetic about their identities generated a similarly passive-aggressive response.

Basketball of the era had Hoya Paranoia. In college football, punditry clicked their tongues at Miami. There may not be a more crystallizing example than the lead-up to the 1987 Fiesta Bowl.

Arriving in Phoenix wearing fatigues, the Hurricanes sparked indignation that still resurfaces decades later. The decision was suspect and welcomed criticism, in particular a quote defensive tackle Jerome Brown offered at the Fiesta Bowl's media day: "Did the Japanese sit down with Pearl Harbor the night before they bombed it?"

Distasteful, absolutely — though not necessarily any more so than Penn State players performing a skit at the combined team dinner on Dec. 29, 1986, that joked Miami's White players and coaches only allowed their Black peers to eat at the same dinner table once a week.

Nevertheless, the fatigue-wearing, touchdown-celebrating Hurricanes went into that No. 1 vs. No. 2 game clearly the villains for public purposes. Penn State represented all that was pure and virtuous in sports, which...BIG YIKES, we can say with the benefit of hindsight.

The 1987 Fiesta Bowl may not have been as overt in its racial and cultural subplot as the Miami-Notre Dame game a little less than two years later; "Catholics vs. Convicts" is staggeringly problematic in today's context. The framing of that Fiesta Bowl more accurately reflects the era, however.

A similar narrative played out four years later in the historic Final Four rematch between Duke and UNLV. The Las Vegas Goliath, with its showboating style and primarily Black lineup contrasted against the starring White players at Duke who played for a coach best described as the spirit of William F. Buckley uploaded into a basketball cyborg.

That's not to posit the Runnin' Rebels were without sin, though. Just a few months following the Final Four loss, members of that UNLV team were photographed in a hot tub with a Mafia-adjacent figure known as "The Fixer."

Similarly, while the impetus for some (much?) of the anti-Miami sentiment took root in backwards racial or cultural philosophy, The U was far from innocent. The program's warts began to show on and off the field by the mid-1990s.

FROM DOMINANCE TO DOWNFALL

Despite winning the national championship in 1983, Miami did not coalesce into the swag-exuding team of college football lore until the latter half of the decade. Jimmy Johnson's tenure is far more synonymous with this brand of Hurricanes football, but Johnson had to endure some potholes along the way.

His debut went about as well as a first-year coach could hope: The 'Canes upended top-ranked Auburn to kick off the 1984 campaign, then knocked off No. 17-ranked Florida by two touchdowns to ascend to the top spot.

Then-assistant Butch Davis foreshadowed the bravado that became the program's identity in the aftermath, speaking to the Miami Herald.

He also jinxed the 'Canes, if you believe in such cosmic power. They lost the following week at Michigan, 22-14. The defeat in the Big House preceded a loss to Florida State in the Orange Bowl two games later, the first of two home blemishes in '84.

The other ended in one of the most replayed moments in college football history.

Hail Flutie marked the penultimate Miami loss suffered in the Orange Bowl during the 1980s, though surprisingly, was the first of two straight. The Hurricanes opened the 1985 season hosting Florida and losing by the same margin that marked their 1984 defeat of the Gators in Gainesville.

"Right now I feel as though we're on the verge of being as good as we want to be, but we're not quite there," Bennie Blades told the Orlando Sentinel following the loss. "It was really just a couple of key plays that got us tonight. Game by game we should be able to cut most of that out."

No matter how confident Blades may have been in his assessment, the future two-time All-American could not have foreseen just how right he was that Miami was on the verge.

Some perspective that underscores just how dominant the Hurricanes were in the Orange Bowl between this September loss and when Chris Jones uttered he "never thought [he would] see" a Miami home defeat: Freshmen on the 1994 'Canes roster were fourth-graders in 1985.

Thus, for half their lives, 1994 Hurricane freshmen knew only of Miami owning the Orange Bowl — not just winning in it, but putting an emphatic stamp. Below is the season-by-season average margin of victory:

1985: 37

1986: 25.5; this figure's noteworthy in part because the closest margin of victory, 12 points, came in a Sept. 27 defeat of No. 1-ranked Oklahoma.

1987: 26.7; the Hurricanes blanked No. 10-ranked Notre Dame, 24-0, one week before surviving a 20-16 matchup with eighth-ranked South Carolina.

1988: 29.6; Miami destroyed top-ranked Florida State to open the season, 31-0, then book-ended the season in the Orange Bowl game itself with a 23-3 romp over Nebraska.

1989: 33.2; The U played a largely lackluster home slate in '89, steamrolling bad teams from Cal, Cincinnati and San Jose State, but capped the campaign with a 27-10 win over No. 1 Notre Dame in the regular-season finale.

1990: 28.5; Like 1989, the 1990 Orange Bowl docket leaves much to be desired outside of a 31-22 win over No. 2 Florida State.

1991*: 28.7; This season is of particular significance in the context of the Whammy in Miami, as the Hurricanes completed their final national championship of the original dynasty in a 22-0 rout of Nebraska at the Orange Bowl. The U split that season's national championship with Washington, effectively setting the stage for the encounter three years later.

This was also arguably the most impressive of Miami's perfect campaigns in the Orange Bowl, opening with a 30-point decimation of No. 10 Houston and scoring payback for the 1987 Fiesta Bowl with a 26-20 defeat of No. 9 Penn State.

1992: 27.4; Although it played for a second straight national championship, Miami's lowest average margin of victory at home in five years arguably foreshadowed the program's impending downturn. Among the wins was a 19-16 defeat of a No. 3-ranked Florida State team with Charlie Ward at quarterback, but the week prior was the more concerning result in hindsight.

To share a personal anecdote, it's a game I remember well for having been just a fourth grader — or at least, I remember the finish. I was seated in my family's minivan on the way home from some Saturday outing and my dad had the radio broadcast on as Steve McLaughlin just missed a game-winning field-goal attempt from approximately a mile out.

The 8-7 final wasn't indicative of a bad Miami team; the early incarnation of Arizona's Desert Swarm defense went on to shut out the No. 1-ranked squad in college football, coincidentally the Washington Huskies. This September 1992 encounter did, however, preview what was to come when the programs faced again 15 months later.

At the culmination of the '93 season, Arizona destroyed Miami 29-0 in what was the Fiesta Bowl's only shutout until the 2016 Playoff semifinal between Clemson and Ohio State.

1993: 27.3; While only a slight dip from the season prior, Miami's 1993 Orange Bowl schedule featured no team anywhere near as good as the '92 Florida State Seminoles — nor an equivalent to Arizona.

A 41-17 rout of a middling Memphis bunch to close out the '93 regular season marked Miami's final win in the streak against a Div. I-A opponent. The Hurricanes opened 1994 with a 56-0 thrashing of Georgia Southern, blasted Arizona State in Tempe then had a bye ahead of the highly anticipated Top 20 showdown against Washington.

The Whammy in Miami marked the end of an almost decade-long run, a historic stretch in college football lore that didn't only set a record but changed the game's identity.

It wasn't an official end to the Hurricane dynasty; Miami didn't lose again for the rest of the 1994 regular season and played at the Orange Bowl for a shot at the national championship. However, the end was looming.

As mentioned above, some (most?) backlash to The U's success reflected a cultural attitude — but that doesn't mean Miami was free from sins.

A few months after dropping its second decision in the Orange Bowl on the campaign, a 24-17 bowl-game loss to Nebraska, The U sustained a far more damaging blow that shaped the program's next half-decade.

Following stiff NCAA sanctions and the gradual downward trajectory at the end of Dennis Erickson's tenure as head coach, Miami was not in the national championship picture for the next five years.

WASHINGTON AND THE WHAMMY

Washington isn't a mere accessory to Miami's story. From a purely football perspective, the Huskies' place in this mini-rivalry of the era may be the more compelling.

As mentioned, Washington and Miami split the 1991 championship in a decision that fueled growing calls for a more formal title process. The second split championship in as many seasons (Georgia Tech and Colorado preceded the 'Canes and Dawgs in 1990) led to the Bowl Alliance, which in turn, led to the BCS.

A 1991 matchup between Washington and Miami remains one of the sport's all-time great What Ifs. With Heisman Trophy finalist Steve Emtman at tackle, the Huskies defense ranks among the most fearsome in history. They surrendered more than 17 points just twice all season, allowing 21 in a two-touchdown romp over No. 9 Nebraska in Lincoln, and 21 again in a 35-point Apple Cup walloping of Washington State in which James gave the depth chart's twos and threes field time.

A 34-14 rout of No. 4 Michigan and Heisman winner Desmond Howard in the Rose Bowl would arguably have been enough to warrant an outright championship, if not for the cachet Miami stockpiled in the previous eight years.

Dennis Erickson didn't exactly politick for Miami — nothing comparable to Mack Brown pleading for a Rose Bowl berth in 2004, at least — but he wasn't shy about his feelings when the Hurricanes topped the Associated Press Poll.

"It's great for the program," he said to the AP. "This football team deserves to be No. 1."

For his part, Don James took the more diplomatic approach, even advocating for a split championship.

"I think it would have been a tragedy if one of us didn't get a trophy," James told the AP after Washington topped the Coaches' Poll.

DON JAMES AND TWO DECADES OF DISCONTENT

James never got his shot against Erickson on the field — the legendary Dogfather retired just a week before the 1993 season when Washington was hit with two years of probation and a two-year bowl ban as a result of players working suspect summer jobs.

Needless to say, college football was policed much more aggressively in the early 1990s than it is today.

James' frustration boiled over ahead of the 1993 Rose Bowl when he bristled at a question from ESPN's Mark Schwarz. Quarterback Billy Joe Hobert was suspended for receiving a loan and linebacker Danianke Smith was implicated for selling drugs, incidents University of Washington president William Gerberding called "embarrassing."

Schwarz asked for James' comment, prompting the following via the AP:

"Are you trying to get me to say something bad about my president? That is...ridiculous, Mark. Don't even lead your fucking questions that way. I'm not going to sit here and put up with that shit now, I've already told you."

James, who finished a remarkable 150-60-2 at Washington with six Rose Bowl appearances in 18 seasons, was burned out. He was just 60 at the time of his retirement, nearly 10 years younger than his most celebrated protege, Nick Saban, is in 2020.

History repeated itself last December with Chris Petersen, also apparently burned out, stepping away with still much to give the game.

The 20 years between James and Petersen are marked with assorted on and off-field embarrassments for Washington football. The 2008 season ended with the Huskies finishing 0-12, a decided low point in the altogether disappointing post-James era.

Washington was rarely bad in the years immediately following James' abrupt retirement, including the '94 season. UW alum and James assistant Jim Lambright took over the program in 1993 and went 44-25-1 over six seasons, finished above .500 five seasons, and reached bowl games every year in which the Huskies were eligible.

Still, with a single nine-win season to his credit, Lambright's tenure was a far cry from the perennial Pac-10 title contention of James' career. He was fired following a 6-6 finish in 1998 and was never again a head coach. Lambright died in March of this year.

Rick Neuheisel replaced Lambright ahead of the '99 season. The young, energetic Neuheisel marked a departure for the program heading into a new millennium, and by Year 2, seemed to set Washington on the right path. At the conclusion of the 2000 season, he coached the Huskies to their first Rose Bowl since James' swan song.

The Neuheisel era, however, peaked early.

The 2000s were a lost decade at Washington, including a 1-10 finish before the infamous goose egg in 2008. The sting of a winless campaign pales in comparison to the assorted scandals that plagued the Huskies a decade earlier.

Ten months before Washington completed its oh-for '08 in the infamous Rotten Apple Cup, the Seattle Times ran an in-depth expose that sullied the memory of the Huskies' last conference championship.

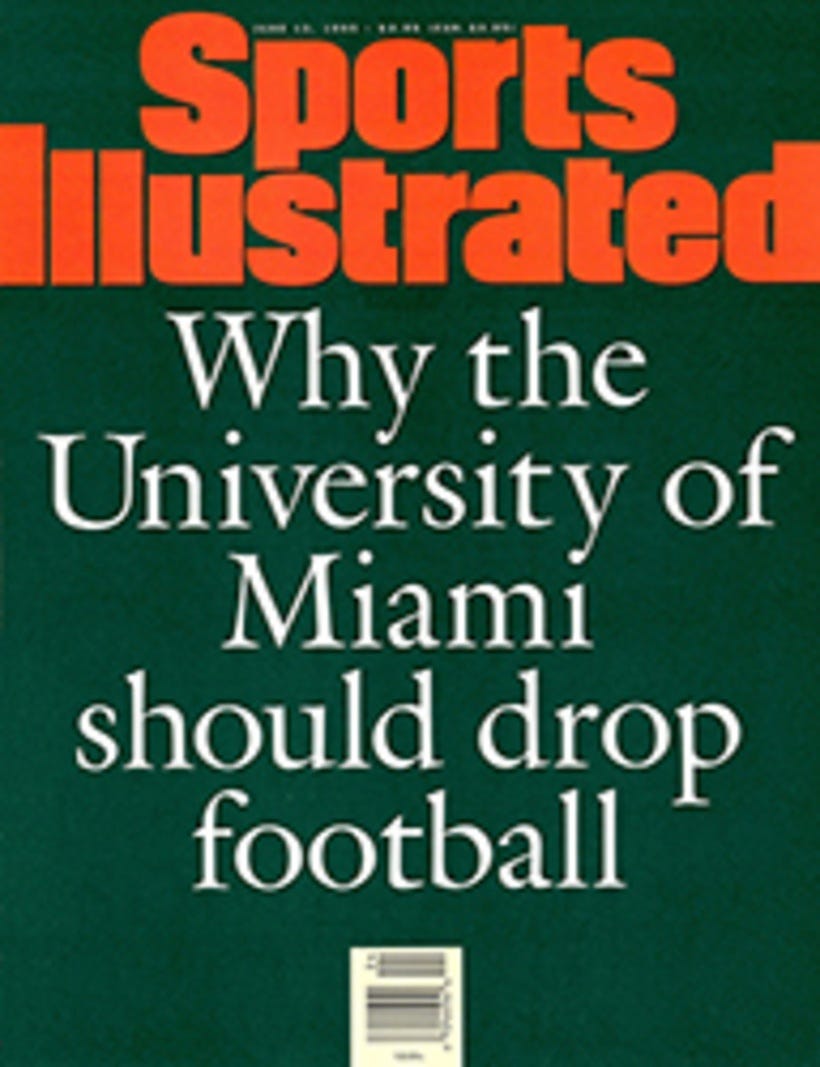

Washington's myriad off-field issues didn't result in a Sports Illustrated cover story at a time when such a gesture meant something, but this marks the darkest period in the program's two decades of struggles.

The Whammy in Miami stands out so prominently in the years between James and Petersen perhaps in part because it's such a rare and untainted high point for the Huskies.

THE GAME

Miami's early drives, as seen in the clip above, suggested another Hurricanes breeze past an overmatched Orange Bowl visitor. And, indeed, The U jumped ahead 14-3 at halftime. Then, things got weird.

“I’m really sort of sick,” Dennis Erickson said to the Associated Press. “I’ve never been around a game like that, what happened in the second half. At the end of the half, I thought we had control of the game. In the second half they dominated the game physically.”

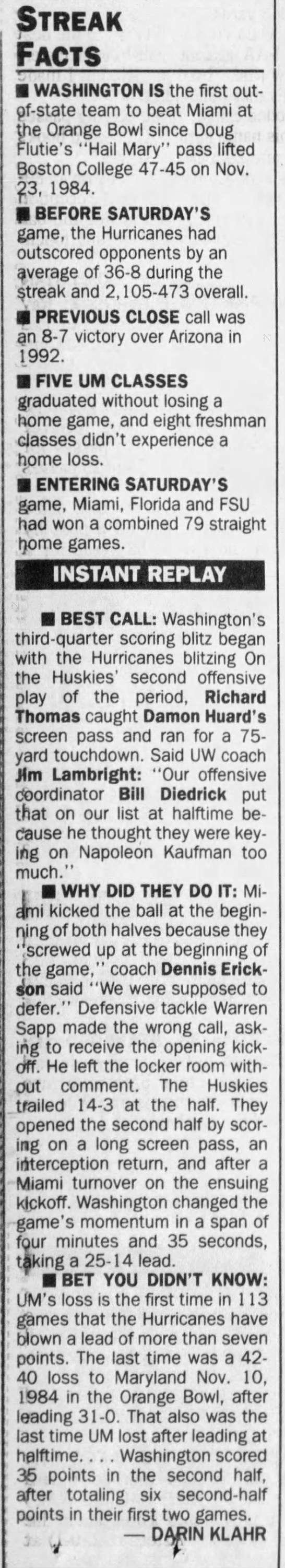

Less than five minutes into the third quarter, Washington erased its 11-point deficit and built a four-point lead on the strength of Richard Thomas' touchdown reception off a screen — a rare fullback score — and a pick-six by Russell Hairston just a few plays later after Miami receiver Jammi German slipped on the turf.

That five-minute stretch fueled a 35-6 second half; hard not to notice the irony in Washington outscoring Miami by the same margin that was right around the Hurricanes' average margin of victory during the streak.

Perusing Florida newspapers from the following Sunday is like reading various obituaries. The Palm Beach Post included a sidebar with assorted facts about the streak, all of which serves to underscore just how long it had been since Miami lost in the Orange Bowl.

EPILOGUE

Former Jimmy Johnson assistant Butch Davis returned to Miami a season after the Whammy, and began a rebuild of The U that was somewhat thankless. The aforementioned 30 for 30 features a number of interviews that disparage Davis, blaming the coach for the underwhelming half-decade between the 1994 season and a return to prominence in 2000.

Chalk those up to lingering bitterness over his departure for the NFL's Cleveland Browns.

Reintroducing Schnellenberger's blueprint of aggressively recruiting local high schools above all else, Davis signed arguably the greatest collection of talent ever on one roster. The 2001 Hurricanes blasted virtually all comers en route to a perfect season and the program's first national championship in a decade — and last title since.

Among Miami's victims in the unforgettable 2001 campaign? The Washington Huskies. A receipt for the Whammy came in the form of a 65-7 deconstruction.

Larry Coker inherited a group Davis assembled that resulted in 38 draft picks. Although Coker came a blown pass interference call away from back-to-back national championships, the quick slide of the program from 2004 on sent The U into a tailspin from which it's never recovered.

Alum Mark Richt flirted with national relevance in 2017, coaching the Hurricanes to the brink of the College Football Playoff and earning a bid to the Orange Bowl Classic. The introduction of the Turnover Chain that season signified a restoration of the signature Miami swagger that defined the program's dynastic era, but in that is an important reminder few quite seem to grasp: Genuine swagger comes after the wins, not before.

In hindsight, the 2003 Fiesta Bowl loss to Ohio State marked Miami football's parallel to the climax of Miami-based Scarface, released the same year as the program's first national championship.

Miami played its final game in the Orange Bowl on Nov. 10, 2007. Before the ACC contest against Virginia, then-Canes quarterback Kyle Wright told the Associated Press:

"We're playing for all the millions of people who've walked through that Orange Bowl and saw a game and all the old players, whether they're still here or not. We're playing for a lot. It's going to be a special night."

Miami lost, 48-0.

The anti-climactic end to the Orange Bowl speaks to the program's decline, but more importantly, outlines a bleak future still unfolding. The Orange Bowl was old, built in 1937, and faced pushback on attempted renovation efforts.

I contend The U will never reach the same heights as it did in the 1980s and early 2000s so long as it continues to play at Pro Player/Landshark/Whatever-The-Hell Corporate Sponsor It Has Now Stadium. A soulless NFL venue located a 45-minute drive from Miami's Coral Gables campus adds an especially high hurdle for cultivating a passionate fan base in a city that inherently cares only when teams are in championship contention.

While the years after the Whammy saw Miami take on jewelry in the form of the Turnover Chain, a member of the Washington team responsible for the Whammy collected some hardware of his own.

Bob Sapp, a Huskies offensive lineman, transitioned to MMA and pro wrestling once his professional football career floundered. Sapp became a sensation in Japan, and in 2004, became the first and still only Black man to ever hold New Japan Pro Wrestling's IWGP Heavyweight Championship. But Sapp’s sometimes-remarkable, sometimes-ridiculous story is one for another time.

Great read, Kyle.

Something else I remember about the "Whammy in Miami" was that, growing up in CT we had to watch it since it was a regional broadcast (Big East, I guess). I was mad that we didn't get to watch Colorado/Michigan instead, and we all know how that game ended.