Seven teams ushered in the Pacific Coast Athletic Association in 1969. Five finished the league’s inaugural campaign with records above .500, albeit against less-than-ambitious schedules in a few cases.

Dead Football Conferences, Part 1 Chapter 1: Big West Football Was Born To Die

Completion of the 2023 college football season effectively signals the end of the Pac-12 Conference. It’s a reality that hasn’t truly sunk in for me. Maybe subconsciously, I’m holding out hope John Cusack will challenge Norby Williamson to a winner-take-all downhill ski race with the Conference of Champions’ fate in the balance, delivering a 23rd-hour m…

Fresno State, for example, went 6-4 but just 1-3 against PCAA competition. The Bulldogs wins included Cal Poly Pomona and the future Cal State Northridge, Valley State — though, to Valley State’s credit, it capped 1969 destroying another PCAA member, Cal State LA, 47-6 at the Rose Bowl.

Chief among the PCAA teams with winning records in the conference’s debut season, however, was an undefeated San Diego State bunch. And SDSU was legit.

The Aztecs scored 47.3 points per game en route to an 11-0 mark and Top 20 finish in the UPI Coaches Poll at No. 18.

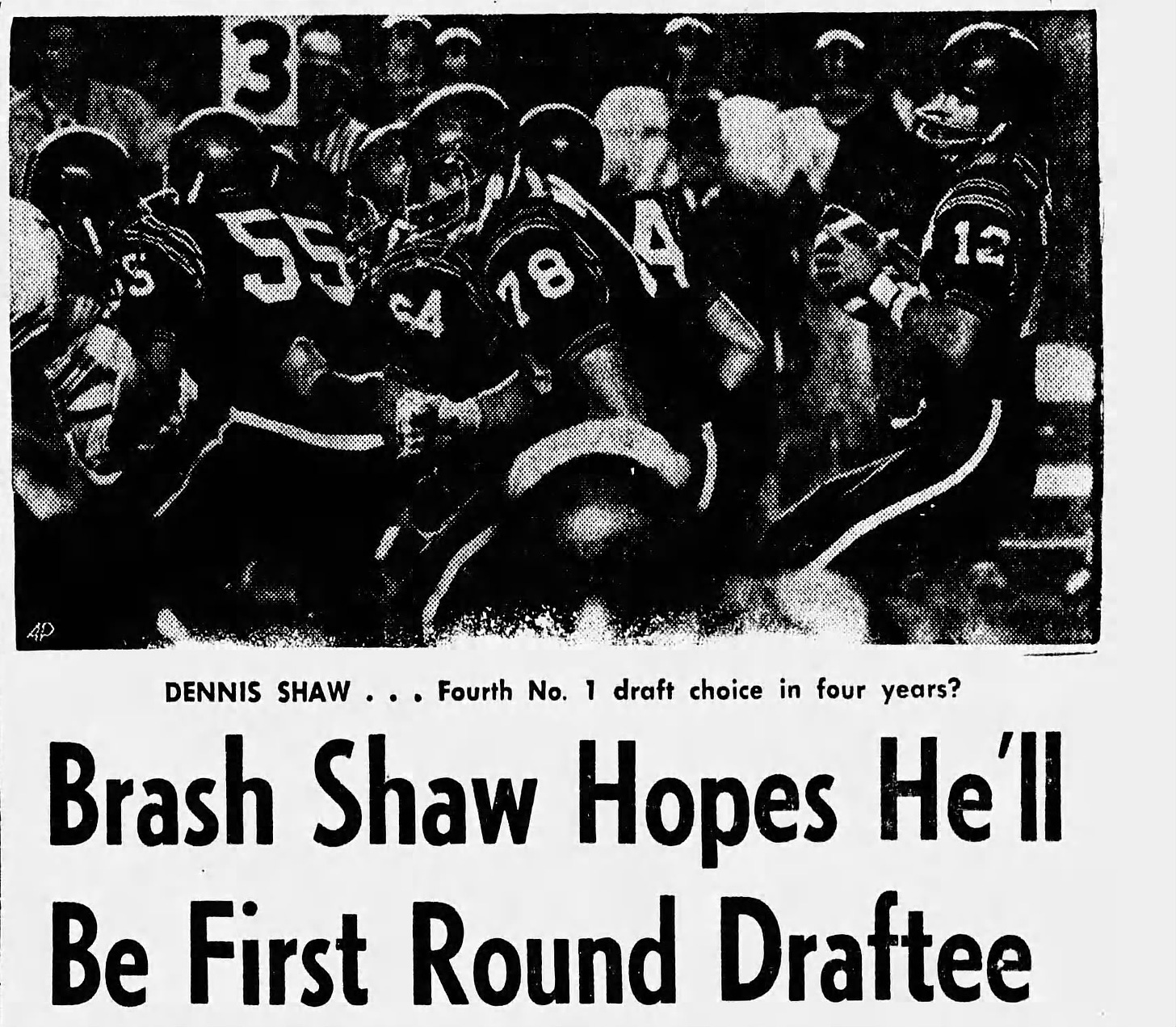

Quarterback Dennis Shaw passed for 3,185 yards with 39 touchdowns and receivers Tim Delaney and Tom Reynolds went for 1,259 yards with 14 scores; and 885 yards and 18 touchdowns.

Those are outstanding passing-game numbers by 2024 standards; in 1969, they were revolutionary.

Shaw touted himself as worthy of a first-round NFL draft pick at quarterback — not a bad turnaround for a one-time USC linebacker who couldn’t see the field.

Shaw went in the second round, but he won Rookie of the Year for the Buffalo Bills in an otherwise middling pro career.

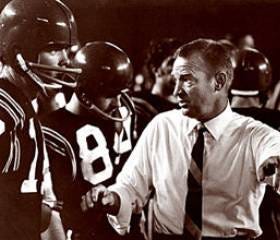

Others from the Air Coryell system, however, flourished in the NFL. Chief among them were Shaw’s back-up in 1969, Brian Sipe; and Coryell himself, who is better known in San Diego for his exploits coaching the Chargers than for his transformative tenure on Montezuma Mesa.

California's Cradle of Coaches Shaped College Football History

Tucked away in the mountainous part of northeast Los Angeles County is a cluster of smaller universities, renowned for their academics. These are schools known for producing celebrated professionals in a variety of fields — among them former presidents Barack Obama (Occidental) and Richard Nixon (Whittier).

Before the NFL lured Coryell away, with the coach accepting the St. Louis Cardinals vacancy ahead of the 1973 season, college powerhouses had taken notice. Rumors swirled ahead of San Diego State’s first bowl appearance in the PCAA era that Wisconsin was making overtures.

Now, Wisconsin hit especially hard times after facing USC in a de facto national championship matchup at the 1963 Rose Bowl Game. The Badgers finished 5-4, 3-6, 2-7-1, 3-6-1, 0-9-1, 0-10 and 3-7 under Milt Bruhn and John Coatta before Coryell was offered the post.

Wisconsin was a bad team — but it was still a Big Ten team. Seven years earlier, it proved capable of competing for a national championship.

Imagining an alternate reality in which Don Coryell goes to Madison and brings Air Coryell to the 1970s Big Ten sends my mind down a dangerous rabbit hole from which I may never return, a la Total Recall.

But that’s a topic for another time. One need not wonder about the potential of Coryell’s offense at San Diego State in 1969. Coryell’s teams were operating with such efficiency for almost a decade by that point, but the move to the PCAA was a chance for San Diego State to present it on a bigger stage.

And the major programs indeed recognized, hence Wisconsin’s interest. Ditto those that shied away from facing San Diego State at season’s end.

The Pasadena Bowl

One of the selling points for the PCAA upon launch and presented to prospective members was a tie-in with the Pasadena Bowl. The Pasadena Bowl launched in 1946 as the Junior Rose Bowl, and true to its name, featured junior-college programs.

Upon rebranding in 1967, however, it made a go of it as an NCAA bowl game. Association with the fledgling PCAA was a positive step toward legitimacy, and the Pasadena Bowl’s organizers made an honest effort to build a big-time event in 1969.

To wit, the Pasadena Bowl made efforts to bring Florida State to California for a matchup with the Aztecs. Florida State balked, per Los Angeles Times reporting, because its administrators viewed the matchup as a no-win situation for the Seminoles.

Win, and they simply beat an opponent pundits believed they should. Lose, and it was a demerit for the program as a whole.

Arizona State also reportedly turned down an invitation to the Pasadena Bowl — an ironic twist, given the valid lament just a year later when the undefeated and nationally ranked Sun Devils struggled to get a bowl matchup worthy of their standing.

Coincidentally, Florida State came west for the postseason a year later to play Arizona State.

The Sun Devils won a 45-38 shootout in the inaugural Fiesta Bowl, which more than 50 years later ranks among the most prominent bowl games. The Pasadena Bowl didn’t make it through the ‘70s, and went out after reverting back to its previous JUCO showcase format.

Also defunct from that 1969 Pasadena Bowl is San Diego State’s opponent, Boston University.

The Terriers were still competing in the College Division in 1969, playing a schedule primarily made up of opponents from a forerunner of the present-day CAA1.

Although 9-1 heading into the Pasadena Bowl record, BU was a considerable step down in significance for San Diego State to face when compared to Florida State, Syracuse (the opponent Coryell himself lobbied to play), and even Arizona State.

The Terriers put up a fight — the headline from the following day’s Press-Telegram reads “Boston Terriers Not Pups, After All — Shake ‘Patsy’ Tag in Pasadena Bowl.”

But San Diego State still won by three touchdowns, 28-7.

Making Potatoes Out of Lemons

The Big West began its football life with a postseason win and went out with a postseason win.

In 2000, the league limped to an end with a geographically mismatched hodge-podge of members. Of the six teams in the final incarnation of Big West football, only one finished with an above-.500 record: Boise State.

Boise State was in just its fifth season of Div. I-A membership in 2000. The next season and its first in the WAC is commonly considered the coming-out party for the Broncos on the national stage, thanks to their win over No. 8-ranked Fresno State.

However, Boise State closed out its brief Big West tenure with back-to-back 10-win seasons capped in bowl victories.

The first, to cap the 1999 season, was a 34-31 thriller against Louisville. I didn’t see this game live, so I don’t have the memories of it that I do the incredible matchup of these same two programs in 2004 at the Liberty Bowl.

Thanks to YouTube, I gained an appreciation for the predecessor five years earlier.

Boise State followed up in 2000 in the final game ever involving a Big West Conference football member, beating UTEP, 38-23.

Both games were played on Boise State’s home turf in the then-fledgling Humanitarian Bowl.

Before it became the Famous Idaho Potato Bowl and introduced the concept of dumping wacky stuff on the winning coach in the postgame celebration, the Humanitarian Bowl was the Pasadena Bowl’s spiritual successor in that it formed to give the Big West a postseason opportunity.

It’s bewildering to think of a time when there weren’t enough bowl games to accommodate every team with a winning record, let alone nine-win conference champions. However, that was the scenario the Big West faced when the Las Vegas Bowl opted out of its automatic invitation for the Big West champion in 1996.

The Las Vegas Bowl filled that role when the California Bowl, which launched in 1981, went belly up in 1991.

Working on this feature about the history of bowl games and TV for Awful Announcing a few weeks ago, I noted a columnist who dismissed the 1984 edition of the California Bowl as “minor-league” despite being ESPN’s first foray into independently produced bowl coverage.

Until its demise, I don’t believe the California Bowl ever shook off that perception — even if it featured Top 25-ranked teams three times in its brief history, all three of which were with ranked Big West representatives.

Just a year after this column deeming it minor-league, the California Bowl had a Top 20 showdown between No. 18 Fresno State and No. 20 Bowling Green.

The 1984 California Bowl featured Randall Cunningham quarterbacking a 10-2 UNLV team that only lost to a top 10-ranked SMU and a 16-12 grinder at Hawai’i that functioned as a quintessential Dick Tomey-style game.

So, no, Big West champion UNLV was not “minor league” in execution. Perception was another matter.

Case in point, the Rebels claimed the conference championship on the strength of a 26-20, late-season win over Cal State Fullerton. The Titans were undefeated heading into the matchup and finished 1984 at 11-1.

The Freedom Bowl, played in Anaheim, was interested in the local team. But losing a road nail-biter to an opponent deserving Top 25 consideration became reason enough for the Freedom Bowl to pass on the Titans, instead inviting a disappointing Texas team.

The Longhorns arrived in Orange County at 7-3-1 after having been ranked No. 4 to open the season and as high as No. 1 before crashing on the back-end of the schedule.

They summarily lost a 55-17 laugher to Iowa, giving up 31 points in the third quarter.

This video on Cal State Fullerton’s Freedom Bowl snub provides further context. It’s well worth your time.

Present-day lamentations about bowl over-saturation aren’t without merit. However, the most common refrain focuses on 6-6 power-conference teams appearing in them as if it’s a new phenomenon tied to the explosion of bowls in the 21st Century.

The 1984 postseason disproves this myth, between the Freedom Bowl opting for a 7-3-1 Texas vs. 7-4-1 Iowa matchup over 11-1 Cal State Fullerton getting a shot at a marquee opponent and an hour south in San Diego, undefeated BYU being paired with 6-5 Michigan in the Holiday Bowl.

The ‘84 Cougars are the last non-power conference team to win a national championship, and it’s damn-near impossible to bring up that point 40 years later without someone pointing out BYU beat an unranked, 6-5 Michigan in its bowl game while second-ranked Oklahoma lost to No. 4-ranked, 10-1 Washington in its bowl.

And the college football cynic in me says that’s not an accident.

Outsiders have long struggled to get any opportunity in the sport’s postseason. Ergo, the Pasadena Bowl was necessary to the PCAA’s launch, the Las Vegas Bowl’s affiliation in 1992 was central to keeping the Big West alive amid departures and closures, and the Humanitarian Bowl kept the league around just long enough to facilitate the rise of a new national power.

As for getting an opportunity against a big-name opponent? That’s a battle fought well into the 21st Century, as undefeated teams like Tulane in 1998 and Marshall in 1999 were passed over for Bowl Championship Series appearances.

And while Utah is officially the first outsider to play in a BCS bowl, the undefeated Utes being paired with an unranked, overmatched Pitt team in the 2004 season’s Fiesta Bowl felt like the BCS offering up a patronizing, conciliatory half-measure.

Boise State was the first outsider to really get a crack at a prominent bowl in the modern era.

College Football's Crossroads Intersect at Boise State

LOS ANGELES — No program through the first two decades of the 21st Century more consistently ran up against but also chipped away at college football’s glass ceiling than Boise State. With the sport amid a period of more major changes in a shorter span than any time since in modern history, the Boise States of the world perhaps face an even stronger barrier between them and the game’s upper echelon.

Just six years after the collapse of the Big West and seven following the Broncos’ first Div. I-A/FBS win in the fledgling Humanitarian Bowl, their 43-42 defeat of Oklahoma in the Fiesta Bowl made a statement — the same statement the Don Coryell made when he took his offense to the NFL and proved it was no gimmick with six playoff appearances in eight years.

Roots planted in the Big West sprouted in ways that left prominent impressions on the game. It may not have been appreciated in its own time, but the conference was not “minor-league.”

Of its 10 regular-season opponents, College Division independent Boston U. played UMass, UConn, Maine, Rhode Island and Vermont, all from the Yankee Conference.