Completion of the 2023 college football season effectively signals the end of the Pac-12 Conference. It’s a reality that hasn’t truly sunk in for me.

Maybe subconsciously, I’m holding out hope John Cusack will challenge Norby Williamson to a winner-take-all downhill ski race with the Conference of Champions’ fate in the balance, delivering a 23rd-hour miracle.

I certainly wouldn’t deem the Pac-12 Better Off Dead, though it’s hardly the first league to go belly up. The Pac-12’s extinction is the most dire in that it’s the first1, and assuredly not the last, major conference to do so.

What had before been a drip-drip-drip of conferences withering away amid changes to the greater college football landscape is progressing with the force of a fire hose today. I don’t feel it’s alarmist to suggest the Atlantic Coast and potentially Big 12 Conferences face dire realities in the not-too-distant future.

Remembering previous leagues that now inhabit the gridiron graveyard paints a picture of how the sport reached its current state. Since this subject started with the West, we stay in the West for our first installment of Dead Conferences — specifically, the Big West.

Readers of The Press Break know the illustrious history of Big West basketball, from Jerry Tarkanian’s Long Beach State teams of the 1970s, to the rising tide of Tark’s UNLV squads in the ‘80s and early ‘90s.

Big West Basketball Is Quietly Commanding Your Attention

Western college basketball’s landscape is crowded with stories this season. It’s the last campaign for the Pac-12 as we know it, a Mountain West Conference that produced the national runner-up a season ago may be the best collectively it’s ever been, and Grand Canyon’s continued rise from the WAC begs a conversation about the implications of a for-profi…

But the Big West also facilitated the rise of football coaching legends, provided the initial platform for an unlikely national powerhouse, and hosted some nationally underrated rivalries.

Throughout this offseason, The Press Break will dig into the histories of dead football conferences

** *

The story of Big West football’s demise is in part the story of Los Angeles-based college football’s downfall.

And, indeed, from its launch in 1968 until its final season in 2000, the Big West hosted five members that shuttered football — four of which were in Los Angeles or surrounding counties.

Two-Team Town: A History of College Football in Los Angeles

Maybe it’s the San Gabriel Mountain backdrop against which the Rose Bowl sits, or the iconic Hollywood sign and skyscrapers of downtown Los Angeles visible from Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. Perhaps credit belongs to the contrast of USC’s cardinal-and-gold against UCLA’s blue-and-gold, making for what’s undeniably the most aesthetically pleasing unifor…

However, the collapse of football in Southern California is only one chapter for a conference that spanned as far north as Idaho and east to Louisiana.

Big West football history begins in 1968 under the Pacific Coast Athletic Association banner. The PCAA hosted its first competitions in the ‘68-’69 academic year, though football didn’t start until fall 1969.

However, football membership was a primary selling point.

Big West Football Is Born From The WCAA

Charter members of the PCAA included UC Santa Barbara and San Jose State, both of which left the West Coast Athletic Conference specifically because the PCAA hosted football.

The WCAC — rebranded in 1989 under its present-day moniker, the West Coast Conference — launched in 1952 as a basketball-only league. And it’s been one helluva basketball conference throughout its existence, hosting two-time national champion San Francisco, the revolutionary Loyola Marymount teams of the late 1980s, modern-day powerhouse Gonzaga and its consistently strong rival Saint Mary’s.

Final Four Fact February: The Legend of Bill Russell Begins

Let’s start this edition of Final Four Fact February with a recommendation of the new Netflix documentary chronicling the life and career of Bill Russell, Legend. A must-watch for any basketball fan.

Prior to the formation of the California Basketball Association, forerunner to the WCAC, universities that made up the fledgling league included some impressive football programs.

Before becoming head coach at Florida during the World War II years, Tom Lieb headed up some successful Loyola Marymount teams in the 1930s, including going 14-4-2 from 1933 to 1934. In that time, the Lions beat noteworthy opponents including Arizona, Arizona State and Texas Tech, with 3-of-4 losses coming against USC and UCLA.

Loyola Marymount peaked in 1950, its penultimate season sponsoring football, with an 8-1 mark and final Associated Press Top 25 ranking of No. 20. The ‘50 Lions featured Don Klosterman at quarterback, who became an influential executive both in shaping the Houston Oilers during the franchise’s AFL days; and leading the Los Angeles Rams during their most successful decade.

Klosterman and the 1950 Lions nearly ran the table, losing only a 28-26 heartbreaker to another university that became a WCAC/WCC member: Santa Clara. Santa Clara was the most consistently successful of the future WCAC partners.

Under coach Buck Shaw, Santa Clara finished ranked No. 15 or better in the end-of-season AP Poll six times from 1936 through 1949, peaking with back-to-back top 10 finishes in 1936 and 1937.

The Broncos went 17-1 in those two years, the lone defeat coming in 1936 against that season’s Cotton Bowl Classic winner, TCU.

Santa Clara won its bowl game in the 1936 season, however, beating second-ranked and undefeated LSU in its own backyard — the Sugar Bowl — 21-14.

The Broncos returned a year later and beat LSU again, 6-0. The scoreless rematch proved pivotal in the direction of college football with a stymied LSU goal-line possession underscoring the absurdity of a rule that gave the defense a touchback if an offense threw three unsuccessful passes into the end zone.

Santa Clara returned to another prestigious postseason showcase in the 1949 season, and turned back another SEC opponent in Kentucky at the 1950 Orange Bowl, 21-13.

Evidently, It Just Means More at Santa Clara — or it did until 1952 when the program shuttered.

College football lost a variety of teams in the early 1950s, most a direct result of the Korean War and coinciding economic downturn once the post-World War II boom subsided.

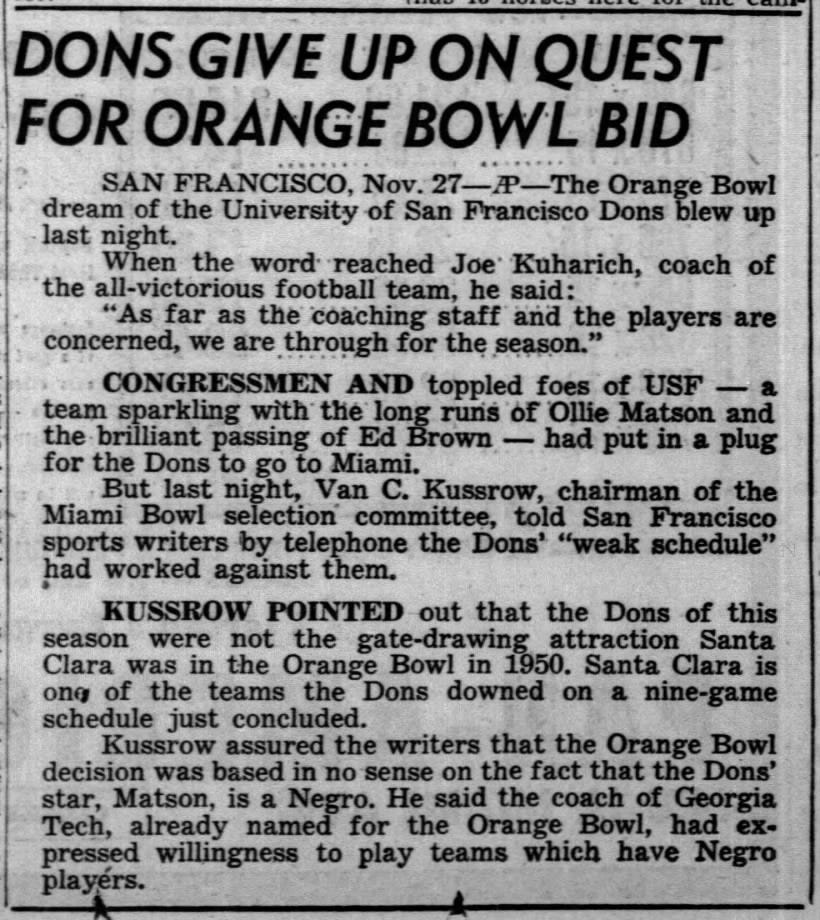

Perhaps most famous of the era’s closed program was another future WCAC member, San Francisco. The 1951 Dons went undefeated with a roster boasting numerous future pros — including Ollie Matson and Burl Toler, two Black athletes. That’s a noteworthy fact, as their presence on the USF roster has been a point of contention for years.

Some believe San Francisco was snubbed by the Orange Bowl specifically because of its integrated roster. The Orange Bowl itself has contended, including in recent years, this is false and cite the Dons’ “weak schedule” — an explanation given at the time, albeit a rather dubious one in light of Santa Clara’s appearance in the game two seasons prior.

Wherever reality lies, the end result is that San Francisco ranks among the once-thriving football programs that shut down once the WCAC was formed. And that’s an integral part of Big West football history, with the lack of sponsorship prompting UCSB and San Jose State to leave, followed shortly thereafter by Pacific.

“Suicidal, But Fun”

The above subheading comes from the headline of a 1968 Salt Lake Tribune column on the pursuit of big-time college football out West. Specifically, John Mooney’s commentary on the formation of the PCAA — erroneously labeled the PCAC in the piece — and the Big Sky exploring the possibility of hosting University Division football is introduced as “‘Keeping Up with Joneses’ May Be Suicidal, But Fun.”

A variety of hinge events over the last 50 years contributed to the sport’s current state, including the late ‘70s separation of Div. I into two subdivisions, the 1984 Supreme Court decision on TV rights and the formation of the College Football Playoff.

The end of the College Division and University Divisions wasn’t one of those hinge events, but it the event leading to such an event. The restructuring at the end of the 1960s set in motion what became the split of Div. II, Div. I and the formation of Div. I-A/I-AA, much the same way that the Bowl Coalition/Bowl Alliance and BCS laid the groundwork for the Playoff.

A fascinating statistic from Mooney’s column notes that in 1961-62, universities that by modern-day distinction would be classified as “powers” averaged $453,025. Just five years later, in 1966-67, that number ballooned to $865,150.

Fast forward to 2000, the final year of Big West Conference football competition, and the exponential growth in the five years from 1962 to 1967 feels quaint in comparison.

Budgets at the onset of the 21st Century grew to $40 million on the low end of the major college football spectrum to $80 million on the high end.

San Jose State — no longer a Big West member in 2000 despite having been a key addition at the time of its launch — had an $11 million budget in 2000. Mooney’s 1968 declaration that attempting to keep up with the marquee names in college football would prove “suicidal” proved somewhat prophetic.

In the three decades between the inaugural PCAA football season and the finale of Big West football, the former members that had to kill off their programs were:

UC Santa Barbara: Following finishes of 6-4, 2-9 and 3-8 in the three initial seasons of the PCAA, UCSB brass shuttered the program immediately following the 1971 season.

The athletic department made an effort to meet the budget with its scheduling that season, putting the Gauchos in buy-games at Washington and Tennessee to open ‘71; and, per the Associated Press report of the program’s shuttering, the department seemed intent on restarting football sooner than later by bringing back the well-tenured Jack Curtice as athletic director.

Fifty-three years later, UCSB football has yet to restart.Cal State Los Angeles: In 1964, Homer Beatty coached the Diablos to a 9-0 mark and the No. 1 ranking in the College Division of NCAA football. Just a decade later, Cal State LA returned to what by then had been reclassified as Div. II having enduring a humbling stretch of sub-.500 seasons, including a five-year, three-coach tenure in the PCAA that produced 10 total wins and 39 losses without a single conference victory.

By 1978, Cal State LA was done with football.Long Beach State: The above linked look at the death of college football around Los Angeles goes into some depth on Long Beach State, which was perhaps most the impactful and highest-potential of the area programs to go under.

Cal State Fullerton: 2024 marks the 40-year anniversary of a remarkable season for Cal State Fullerton football, which went an official 12-0…but, in reality, finished 11-1.

UNLV beat Cal State Fullerton in a showdown of undefeated teams on Nov. 10, 26-20. The win set the Rebels on their way to the Big West championship and an invitation to the California Bowl. Because postseason opportunities were scarce in the ‘80s, Cal State Fullerton was left out.

Might an injection of bowl money have helped buoy the Titans beyond 1992, when the program closed? Probably not, but it’s an interesting What If to ponder.Pacific: Pacific football ending after the 1995 season would be a minor footnote in the sport’s history, given the program’s consistent lack of success. However, Pacific has a profound impact on shaping modern football in ways that the next chapter of the Dead Conferences will explore.

A sixth Big West member, Idaho, reclassified to the Football Championship Subdivision 16 years after the Big West ceased football operations.

Pac-12 Tuesday: The Idaho Vandals and The Other Time The Pacific Conference Died

Under the cloud of uncertainty looming on the Pac-12 Conference rings a common refrain that 108 years of history are going by the wayside for, what increasingly looks like, media conglomerates to have inventory on their streaming boondoggles. It’s a point I have echoed, and it is technically true despite this not being the first time the Conference of C…

Idaho played in the final Big West season, which was a seven-team hodge-podge of members that either had recently moved up from Div. I-AA — Arkansas State, Boise State, Idaho, Nevada and North Texas had all reclassified no earlier than 1989 — or didn’t get the call from the WAC when it retooled at the end of the ‘90s in the case of New Mexico State and Utah State.

But while a bizarre mix of members, six of which finished below .500 in 2000, carried the banner at the end of Big West football, even in the last season the conference offered something that would mold the game’s identity in the 21st Century.

Stay tuned for Chapter 2 in this series, exploring the Big West’s influence on the sport at large.

One could argue otherwise, depending on their definition of “major.” The Southwest Conference qualifies as major in that it hosted powerhouses Texas and Texas A&M.

However, by its demise in the mid-1990s, crippling NCAA sanctions and assorted other issues had rendered much of the SWC mid-major — thus why half of its final members landed in mid-major leagues (Rice, SMU and TCU in the Western Athletic Conference, Houston in Conference USA) and more than half would have, had Texas Governor Ann Richards not wielded her political influence to bail out Baylor.

The Big East could also be fairly labeled a power conference, having produced a national champion about a decade before its football collapse and being guaranteed Bowl Championship Series status. But, Big East had little history, launching in 1991, and was strip-mined for most of its existence.