Chicago State Football Can Be A Front Porch to More Than Just A University

Representing the city's often-derided South Side, the launch of Chicago State football offers hope for an impact well beyond the university's campus.

In a city that gave birth to college football’s modern-day role within the larger university ecosystem, Chicago State has become the latest institution to turn to the gridiron in hopes of benefiting the entire campus and extended community.

As part of its move to the Northeast Conference this academic year, Chicago State accelerated the process of sponsoring football. That process reached a major milestone on April 8 with the introduction of Bobby Rome II as the Cougars’ first head coach.

Rome’s introductory press conference touched on familiar themes: establishing a winning identity quickly, building that identity through local recruiting, and representing both the university and its surrounding community.

Rome also shared with the Chicago Sun-Times details of his football background that are anything but common — including a stint coaching in Russia, at a school just one errant Kim Jong-Un rocket away from North Korea.

Coming from such a unique and challenging background makes Bobby Rome II a seemingly ideal fit for the most unlikely newcomer to Division I football in recent memory.

In the FBS, six programs have either launched or revived long-dormant football teams since 2009:

Charlotte

Georgia State

Kennesaw State

Old Dominion

South Alabama

UTSA

In the Football Championship Subdivision, which Chicago State will join, several schools have also debuted or restarted football programs since 2008. The most recent addition, UT Rio Grande Valley, is set to play its inaugural varsity season in 2025.

The other seven are:

Campbell

East Tennessee State

Houston Christian

Incarnate Word

Lamar

Mercer

Stetson

Option Offense, '85 Bears Defense & Georgia National Championships: On The Mercer Football Comeback Story

Bobby Hooks was a helluva player for the Georgia Bulldogs in the Roarin’ ‘20s, starring on a team that beat perennial powerhouse Yale in 1927. Hooks’ pass to Frank Dudley set up a critical Georgia touchdown to secure the win, which became the linchpin for the second of four unclaimed national championships in the program's history.

Chicago State shares certain traits with both of these groups. Primarily, all of the FBS newcomers but South Alabama and FCS upstarts UIW and Houston Christian are in major metropolitan areas.

Chicago State’s the only one to launch as just the second NCAA scholarship football program in a major metropolis1, and the sole Div. I football program in its city. And, to be clear, CSU will be the first D-I football team based in Chicago; Northwestern is certainly within the metropolitan area, but on the shores of Lake Michigan in the affluent suburb of Evanston.

CSU football plans to represent the city of Chicago, and more specifically, the South Side. Rome’s introductory press conference embraced the university’s presence in a community that, perhaps more than any other in college football, stands to gain from the idealistic view of the sport’s role.

The much-debated Front Porch2 theory, which states successful athletics attracts support and prospective students to the overall gain of the university, began in the Windy City in 1892. That’s when the fledgling University of Chicago, opened only two years earlier, hired Stagg to head its athletic department.

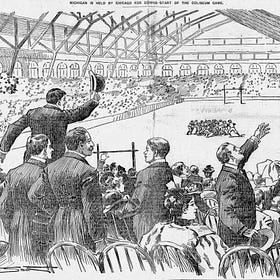

More notably, Stagg was tasked with building the University of Chicago football program. Football’s booming popularity on Eastern college campuses at the end of the 19th century extended to the Midwest, and quickly reached a fever pitch.

The programs that in 1896 formed the Western Conference, today’s Big Ten, were among the most fervent universities chasing gridiron glory in those formative years3. The University of Chicago, which famously hired Stagg before employing a dean, may have been the most fervent, and most responsible for establishing the framework of what we would today call a Football School.

Any history of college football that doesn’t mention UChicago is incomplete. The Maroons packed Chicago Stadium for the sport’s first indoor game, cultivated one of the game’s first truly venomous rivalries with Michigan, helped assert Big Ten excellence with national championships in 1905 and 1913, and boasted the first Heisman Trophy winner in Jay Berwanger.

The Greatest Days in College Football History: Thanksgiving 1896 Gave Us A Modern Game

Scandal, questions of amateurism, a disputed national championship and a conference championship decided on end-of-season tumult: The preceding could describe most any college football campaign of modern times.

And, at the same, the University of Chicago as an institution grew into one of the most academically prestigious in the nation — distinction it maintains today. In fact, as much as college football’s history is incomplete without mention of the Maroons, you’re probably more likely to encounter folks in day-to-day conversation familiar with UChicago as a top-tier academic school than as an influential football powerhouse.

Likewise, in my experience, your chances of encountering someone who knows UChicago football more for the Stagg Field Stadium concealing work on the Manhattan Project than for the Maroons winning multiple national titles.

In this regard, UChicago’s trailblazing use of football both validates and refutes the Front Porch theory. Stagg’s groundbreaking Maroons certainly gave the brand-new university a public profile that facilitated its growth into the elite academic institution it remains today.

At the same time, UChicago maintained and even furthered its academic standing well beyond shuttering its scholarship football program in 1939. It could be argued UChicago’s academic grew because it untethered its identity from big-time football; that was the motivation of university brass that made the decision with a declaration that the sport’s growing popularity invited corruption.

Concerns about football’s pervasiveness to the academic mission go back as far as and to some extent predate4 Rutgers and Princeton first squaring off in an informal matchup in 1869. But while a tenuous existence has always been there, the relationship between football program and university has never felt more frayed at the sport’s top level than it does in 2025.

In an era of players spending less than a full academic year on campuses, moving in pursuit of payment offered through third-party channels, big-time football seems less a part of the university ecosystem than a business paying for university licensing.

Chicago State debuting in the FCS suggests university brass harbors no delusions of trying to build community while trying to compete in the cynical, professionalized landscape of the FBS. But Rome and his staff have a tight rope to traverse, because support can’t come without success.

And success hasn’t exactly washed over Chicago State athletics.

Seasons of 11 and 13 wins in 2022-23 and 2023-24 marked Cougars men’s basketball’s first double-digit-win seasons since 2012-13 and 2013-14. This year, CSU’s first in the NEC, the Cougars regressed to 4-28.

A similar lack of success for football is an immediate non-starter in growing a program. Success in FCS is less tied to NIL money than in the FBS, but cannot be entirely discounted in the subdivision.

That’s one potential hurdle to recruiting. Another is indicative of why Chicago State football’s prospective representation of the Front Porch theory is so important: Perception of the South Side.

South Side Chicago has always had a reputation as the grittier part of the community, predating even the Chicago Fire. Much of it is rooted in socioeconomic biases and attitudes toward migrants who moved their for job opportunities, and later the Black community that predominantly lived on the South Side.

But, as with all biases, there are nuggets of truth one can latch onto in order to make sweeping generalizations. To that end, Chicago’s history as one of America’s most violent cities molds a considerable portion of its reputation.

With the exception of a spike last decade, much of the perception about Chicago’s violence comes from the 1970s into the first half of the 1990s.

And, with South Side communities accounting for the highest percentage of violent crimes in Chicago, the area is the epicenter of this overall negative reputation.

To be clear, Chicago’s gun violence is often invoked as a political cudgel; a red herring intended to dismiss gun violence elsewhere by shifting the conversation to another populace. I have rarely encountered this insertion of Chicago into the gun violence epidemic presented with any sort of good-faith solutions to uproot the causes.

The result is a not-insignificant portion of the population describing Chicago in language akin to that of screeching sports-talk weasel Jason McIntyre.

On the flipside, those who ignore both the history of violence in Chicago, the underlining causes, and its continuation — even as cities like Memphis and St. Louis surpass it in murder rate — do equal damage through their apathy.

In the above clip, McIntyre’s otherwise asinine statement unintentionally stumbles onto an instructive point about Chicago’s perception. In likening the Windy City to Afghanistan, there is indeed a fascinating parallel to be made: It’s that we collectively in our society love to make authoritative declarations about places we’ve never been, don’t understand and offer no attempt to understand.

To that end, Chicago State’s part in the old Front Porch theory extends beyond the university and to an entire community. If Cougars football can provide a portion of the country a more welcoming glimpse at the South Side, the program’s a winner regardless of its record.

The first is Roosevelt University, which debuted in Div. II last season. I spotlighted the Lakers for FloFootball.

Obligatory shoutout to Craig Meyer’s terrific Front Porch newsletter, which any fan of college sports needs to read.

Another obligatory shoutout, this time for Dave Revsine’s “The Opening Kickoff,” one of my absolute favorite books on college football.

The first college football game spawned directly from an annual tradition among Princeton undergrads called “balldown,” which as it’s been described seems less like football and more like a schoolyard game past generations called Smear The [derogatory term]. Accounts I have read suggest Princeton professors were not keen on the yearly balldown contest.

Insightful socioculturalsport commentary, Kyle.