Scandal, questions of amateurism, a disputed national championship and a conference championship decided on end-of-season tumult: The preceding could describe most any college football campaign of modern times.

But, in this context, it describes the final full day of the 1896 college football season.

This edition of Greatest Days throws it back to a time when, on the gridiron, one only could throw back. The forward pass was not yet universally legal until a decade later.

We rewind to Thanksgiving Day, Nov. 26, 1896, just a few weeks after William McKinley beat William Jennings Bryan in a presidential election that, for Bryan, began a run of futility that makes Oklahoma’s College Football Playoff misfires pale in comparison.

Football settled on universal rules in the decade prior thanks to Walter Camp, evolving from a game that varied between a hybrid of rugby and soccer depending on which campus it was played in the 1870s. Still, the game near the turn of the 20th Century was vastly different from today in terms of elements like scoring.

1896 was the penultimate year in which field goals were worth more (five points) than touchdowns (four points), for example, though a touchdown and kick after was the greatest value at six points. There’s plenty more which could make for its own separate entry, but I’ll leave it to this notation on scoring for this entry since it plays a direct part in the retrospective.

To that end, I originally intended to avoid the years pre-World War I upon conceiving this series or two reasons: First, I am working on a project that covers the sport’s early years and didn’t want to run the risk of redundancy; and, second, football then was so different in how it was played that it hardly resembles the game played even by the 1920s when passing became more en vogue and helmets — crude as they were then — became standard (though not mandated until the 1930s).

However, the 1896 season offers enough intrigue on its own that it, in some ways, shaped college football as we know it and love it today. Some of the more controversial moments even mirrored the modern sport in an uncanny fashion.

One of my favorite books on the sport is Big Ten Network host Dave Revsine’s The Opening Kickoff, which covers the earliest years of the conference and contrasts public concerns about college football at the turn of the 20th Century with similar issues that resonate today.

Independent of The Opening Kickoff providing inspiration for this particular newsletter, it’s an informative, fun and easy read I highly recommend adding to your summer list.

With that, let’s dive into Thanksgiving Day 1896.

Champions of the West?

Conference affiliations play such a critical role in shaping the history of college football, a point underscored today amid realignment and the consolidation of power among only two leagues.

Conferences’ part in the greater overall framework of the sport began in 1896 with the formation of the Western Conference, today’s Big Ten.

The way in which the Chicago Tribune’s Sept. 30 brief describes the formation of the Western Conference is less the forging of a deep-seeded partnership as it is a basic scheduling agreement.

This agreement was indeed born from monopolization of the national championship, a parallel with the exclusion of certain leagues in the more modern eras of the College Football Playoff and Bowl Championship Series.

Claims to be the sport’s best team belonged exclusively to East Coast universities that led in the formation and proliferation of football in the previous quarter-century — mostly Princeton and Yale, though Harvard claimed the 1890 title and Penn with coach George Washington Woodruff boasted a burgeoning powerhouse in the mid-1890s.

The Quakers staked claim to national championships in 1894 and 1895, with designs on a piece of a third in 1896.

And lest anyone downplay the idea of a “national champion” as a 20th-Century concept retrofitted for the 19th Century teams, consider the newspapers of the late 1800s were indeed touting teams as football’s champions.

Media of the day took these claims serious enough, in fact, that they pushed for matchups between the top teams in hope of truly determining who was best. This headline from a December 1895 edition of the Philadelphia Inquirer calls for Yale to schedule Penn1.

In the spirit of the above sentiment, and to give the schools further West than Philadelphia something tangible to play for, Chicago, Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, Northwestern, Purdue and Wisconsin formed their alliance.

As for the Chicago Tribune’s suggestion of adding both Missouri and Oberlin, there’s fodder for a future What If Wednesday. Until then, though, the original Western Conference sat at seven.

And, in 1896, the collection of schools played in the first-ever true major college football conference. And, setting the tone for the next 130’ish years, the first-ever conference championship came down to a chaotic final day.

Michigan won its initial nine games ahead of Thanksgiving by an average of 28 points per game. The Wolverines didn’t surrender a point over the opening seven, and had only given up a single touchdown in a 6-4 defeat of Minnesota on Nov. 7.

At that pace, the 1896 Michigan Wolverines would have had to play the equivalent of 18 seasons to surrender the point totals Chicago allowed in losses of 46-6 to Northwestern and 24-0 at Wisconsin.

To the Maroons’ credit, those were the only two blemishes in the team’s fifth season under Amos Alonzo Stagg, a coach who ranks among the most influential figures in football’s first 50 years. What’s more, Chicago exacted revenge on Northwestern a week before hosting Michigan in an 18-6 win, and routed what was a good Oberlin program in the era, 30-0.

Still, the Maroons were not on Michigan’s level. Game recaps published in the days following the Thanksgiving matchup declared as much, including the Indianapolis Journal.

“[A]lthough the Chicago eleven professed the utmost confidence of winning this feeling was not shared by their supporters, who, at best, looked for them to hold their opponents down to a low score.”

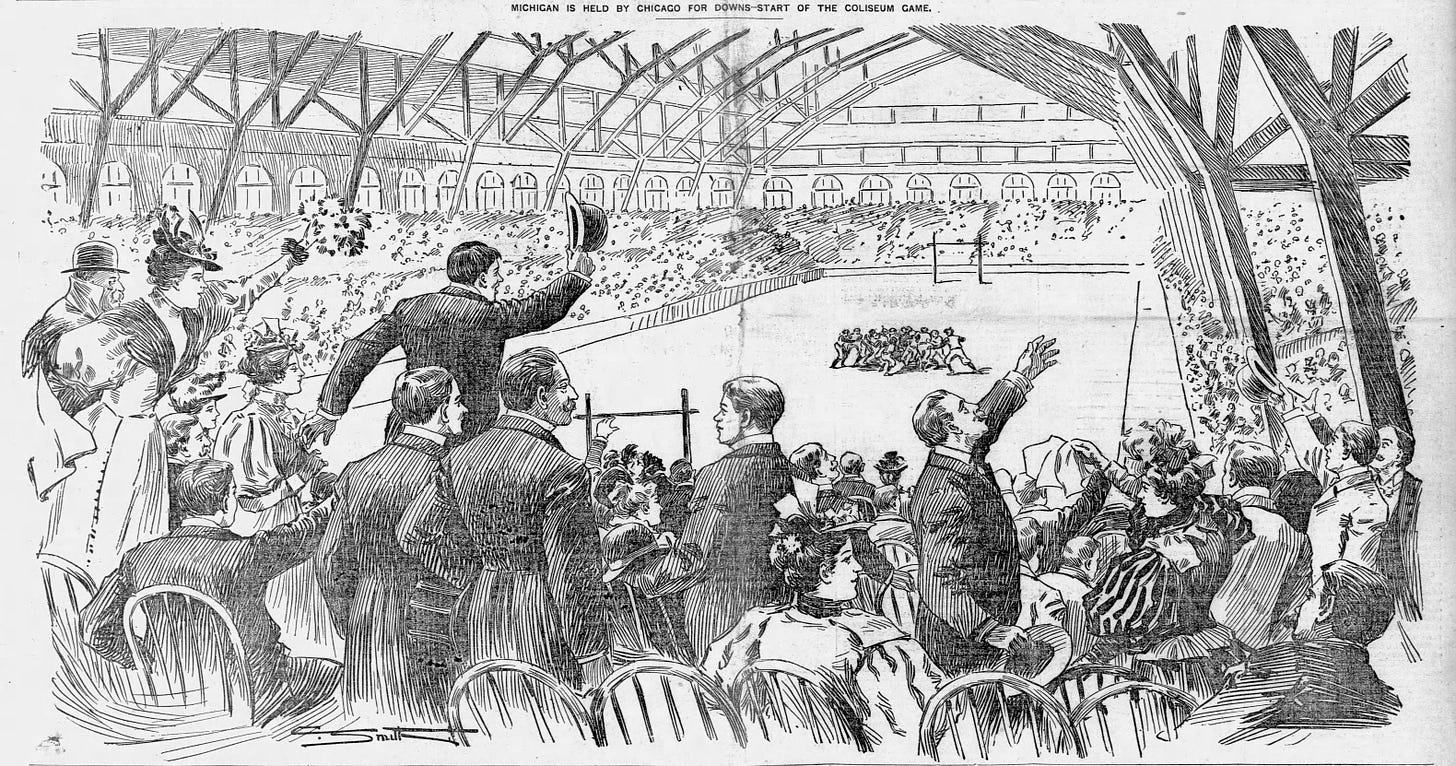

An estimated crowd of between 15,000 and 20,000 packed into the brand-new Chicago Coliseum, which the Chicago Tribune noted in its game recap opened the previous summer as the jumping-off point for William Jennings Bryan’s doomed presidential campaign.

While the Coliseum wasn’t a launchpad for the future with Bryan and the 1896 Democratic Convention, the venue did set a precedent extending into the 21st Century of high-profile college football games played indoors.

This was indeed college football’s first-ever indoor game.

And, as the Chicago Chronicle reported, it’s a good thing the Maroons and Wolverines met in the Coliseum. The Windy City was deluged in an unseasonably warm and heavy rain on Thanksgiving 1896 — keep this in mind.

The Chronicle’s artist rendering of the event offers a brilliant insight into what it was like for those shielded from the rain, taking in a historic football game.

It’s also a good reminder of how far-gone an era this was from our own culturally. Attending a football game in a Victorian dress is an experience that makes the Ole Miss fans wearing tweed blazers in 100-degree heat/95 percent humidity seem downright sensible.

The women in their extravagant hats and the men in their tails and high-collar shirts who filled the Chicago Coliseum took in one of college football’s first high-stakes upsets.

Those Maroons supporters who, as the Indianapolis Journal suggested just wanted to see Chicago hold Michigan “down to a low score” got their wish. Stagg’s bunch allowed a single Wolverines score, which came on a second-half touchdown with the two-point kick after.

The six points would have been enough in any other Michigan contest all season, but Chicago’s Clarence Herschberger — a 1970 College Football Hall of Fame inductee — punctuated a heroic day punting with a touchdown off a Wolverines fumble.

Herschberger’s punting routinely pushed back the Michigan offense, which struggled to gain much ground on the Chicago defense and on one possession lost yardage into their own end zone for a safety.

To their further credit, the Maroons forced a turnover-on-downs at their own 10-yard line in the second half that helped effectively seal the 7-6 win.

Michigan losing on Thanksgiving meant Wisconsin needed only to beat Northwestern not far from the Coliseum in Evanston.

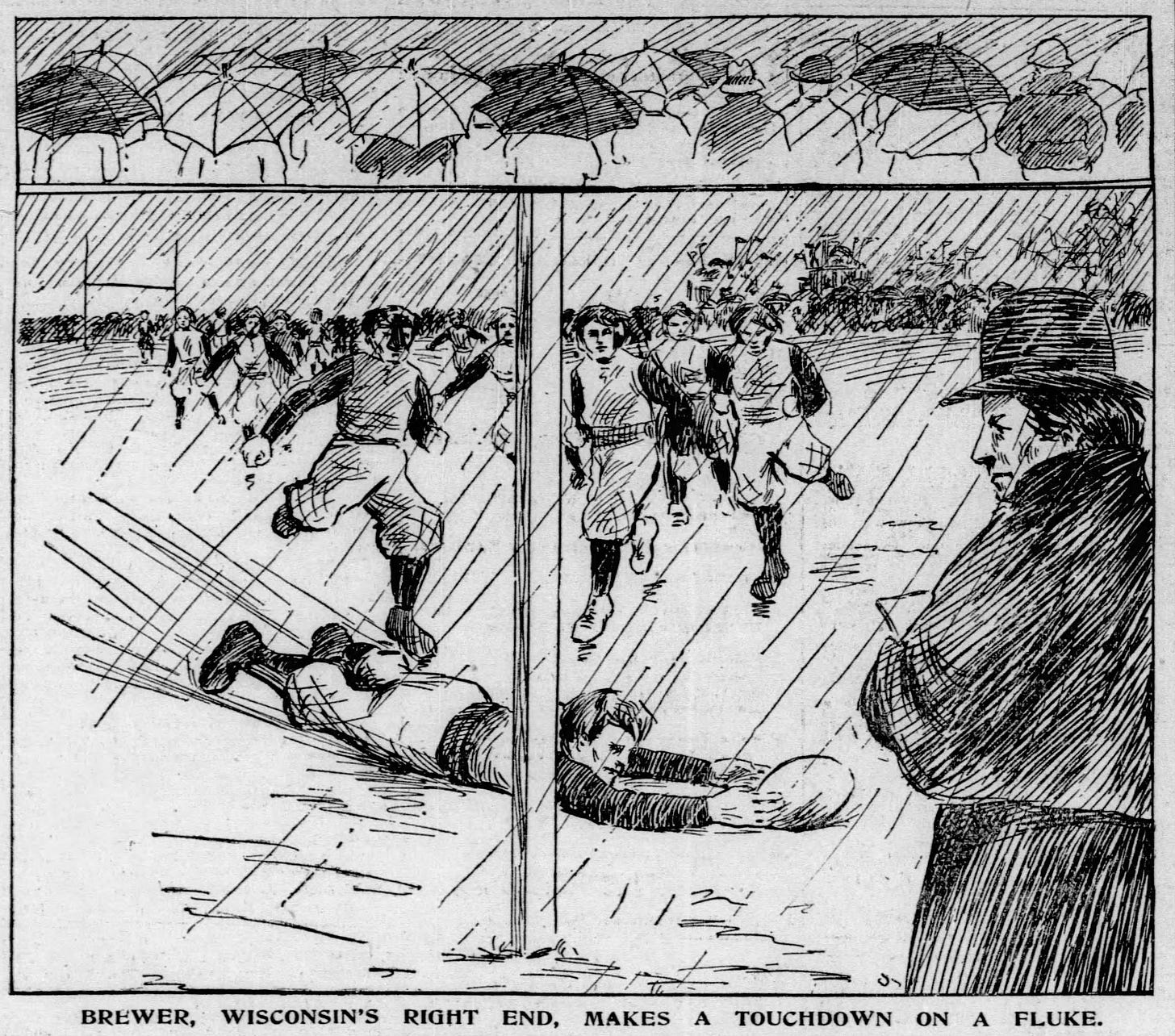

The rain storm that the Coliseum spared Chicago-Michigan? No such luck at Northwestern.

The Chicago Tribune artist depiction of Wisconsin’s lone score — a “fluke” touchdown scored on a sliding play in the rain — offers a nice contrast to the scene from the Coliseum.

That touchdown came courtesy of Chester Brewer, who was later head coach at Michigan State and Missouri, and it ensured a 6-6 tie.

A tie would ostensibly be enough to award the championship to Wisconsin by today’s standards, as the Badgers were otherwise undefeated in the Western Conference. However, cracks in Wisconsin championship claim surfaced when team captain John R. Richards said, via the Chicago Tribune, the Thanksgiving result was “half a victory” for Northwestern.

And thus, with college football’s first conference championship came some of the game’s earliest championship politicking.

The Nov. 28 edition of the Chicago Chronicle ran a headline reading “SAY THEY ARE CHAMPIONS” intro’ing an article on Amos Alonzo Stagg declaring his Maroons champions of the West — a moniker Michigan claimed for its fight song, “The Victors,” two years later.

But two losses in lopsided fashion make Chicago’s stake to the title laughable — so much so that Northwestern issued an immediate challenge for a third game between the neighboring schools that the Chronicle reported received a “curt refusal” from Stagg.

“I don’t care to discuss the matter beyond saying that Northwestern does not claim the western championship,” NU captain Jesse Van Doozer said per The Chronicle. "As I look at it, no team is entitled to the banner, three of them, however, being practically tied, Wisconsin, Northwestern and Chicago. What advantage any one has over the other I am unable to see. I should like to have had a third game with Chicago and think Northwestern would have won.

“Chicago’s refusal of the challenge is the best index to the shallowness of its pretensions,” Van Doozer added.

Is that…is that 19th Century shit-talk? Proto shade-throwing?

That college football in the 1800s had its own version of modern-day media sparring warms my heart.

Champions of the South?

To call the proto-Big Ten college football’s first conference isn’t entirely accurate. The Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association — forerunner to the Southeastern Conference — predates the Western Conference by four years. It Just Means More, after all.

And among the Its the SEC and the league’s ancestor Means More of is claiming dubious championships. Alabama’s 18 claimed national championships include some whoppers, with 1941 being the most preposterous and the logic of back-to-back claims for 1964 and 1965 directly contradicting one another2.

Quizzical championship claims among SEC members predate the conference’s formation, evident in Georgia counting its 1896 SIAA…title…among the program’s 16 all-time conference championships.

To wit, Georgia played two SIAA opponents — the league had 17 members — and was one of three SIAA to finish without a conference loss. One of those three, Tennessee, didn’t play a single SIAA game.

The Vols instead went 4-0 against a schedule of:

Williamsburg, known today as University of the Cumberlands — not to be confused with the Cumberland University program John Heisman famously ran up the score, 222-0, when he was the coach at Georgia Tech in 1912.

Chattanooga Athletic Club

Present-day Virginia Tech

Central, which today is Eastern Kentucky

While SEC honks continue to argue for an eight-game conference schedule in the 2020s, even as the league expands to 16 members, it’s surprising no one has suggested adopting the 1896 Tennessee scheduling model to pad a Playoff resume.

Anyway, to label either Georgia or LSU the 1896 SIAA champion is a stretch.

However, the program that came to be named the Bulldogs circa 1920 — shoutout the great Low Major and its Name-A-Day series for details on the history of college teams’ nicknames — did make some truly significant history on Thanksgiving Day 1896.

With the aforementioned Heisman on the opposing sideline, Georgia faced Auburn in the fourth-ever installment of the Deep South’s Oldest Rivalry.

Page 2 of the Thanksgiving Day Atlanta Constitution was dedicated almost entirely to hyping a matchup the newspaper declared, “Greatest Football Game of the Year.

The public bought in, filling Atlanta’s Brisbane Park to capacity. The Constitution reported the day after that overflow fans took to neighboring rooftops to catch a glimpse.

Spectactors saw a 12-6 for the “Red-and-Black” of Georgia — as well as what early 20th Century football journalist and historian Fuzzy Woodruff declared in his A History of Southern Football was the first-ever successful onside-kick attempt in the South.

The Constitution, in its Nov. 27, 1896 account, described the play coming out of halftime as follows:

“Georgia opened the second half with a surprise for [Auburn]. Lovejoy kicked the ball fifteen yards on an easy roll instead of lifting it over forty yards. The kicker then rushed down the field and placed the ball on side and Nally fell on it.”

The Red-and-Black then drove down the field for their second touchdown, effectively putting the game away. The successful onside kick — as well as the proto-hurry-up, no-huddle described in wire reports that appeared in the Birmingham News, detailing “a series of consecutive plays were sprung upon the Alabamians and took them by surprise. The plays were quick and without a signal and without words,” — were indicative of “heady, tricky playing rather than good, hard football” per Bowdre Phinizy.

“Perhaps no southern man is more versed in the science of football than Bowdre Phinizy,” the Constitution declared in the introduction to Phinizy’s analysis of the game, which contains maybe the first-ever publication declaration of the national superiority of what would become SEC football.

Outsider claim to the national championships Princeton and Yale largely monopolized would indeed come in 1896, but not from the South.

Champions of the Nation?

Beginning with the first set of games played in November 1869, one of either Princeton or Yale staked claimed to essentially every national championship through 1895.

Penn, as noted, was strong enough in the ‘95 campaign that the Inquirer began the public call for Yale to schedule a matchup with the Quakers.

A newcomer into the mix stepped up in 1896, though not without considerable controversy.

In its second game of the campaign, Lafayette welcomed powerhouse Princeton to Easton, Pennsylvania, for a 0-0 that the Philadelphia Times declared “a virtual victory.”

Lafayette “might be instead rejoicing over an actual defeat of her3 strong rival but for the poor display of judgment. She had the best of the fight in the first, and would have scored if she used a diversified style of play.”

The Boston Globe offered a different perspective, suggesting that although “Princeton’s play was not nearly up to standard,” homestanding Lafayette went unpenalized on plays that would have otherwise opened up Princeton scoring opportunities.

Editorializing aside, the tie was the only game Lafayette did not win in 1896. The same goes for Princeton, which ended its season the Saturday before Thanksgiving with an emphatic, 24-6 defeat of Yale before as many as 50,000 fans at Manhattan Field.

Lafayette scored its signature win 17 days later at Franklin Field in Philadelphia, where the visitors stunned defending national champion Penn, 6-4.

Of beating a Quakers side that hadn’t lost since 1893, the Philadelphia Inquirer declared: “A new giant has been born to the gridiron, and it flaunts the maroon and white of Lafayette.”

The Herculean upset very nearly didn’t happen; Penn and Lafayette administrators bickered over revenue distribution, with the former wanting to pay the visitors $500 total from the gate receipts per the Philadelphia Times. Lafayette, which boasted a strong home contingent, sought about one-third of the gate from a crowd that ended up being a reported 13,000 strong.

Cancelled games and the threat of cancelled games was an unfortunate theme of Lafayette’s historic season. Past teams concluded with Thanksgiving games against rival Lehigh, a series that remains one of college football’s most heated and steeped in history to this day.

On Thanksgiving Day 1896, however, Lafayette concluded its season in an 18-6 defeat of Navy.

“Among the many witnesses to the game,” reported the Baltimore Sun, “was a large number of handsomely dressed ladies, some of them strangers who had attended the Thanksgiving dance and had remained over to cheer to victory to the cadets. They were doomed to disappointment.”

Lehigh might have spared those women disappointment had it not cancelled its home-and-home with Lafayette. However, an early-era scandal emerged when Lehigh’s athletic association accused Lafayette star George Barclay of having violated the rules of amateurism as a professional baseball player the previous summer.

The Inquirer’s Nov. 7 edition details a conference between Lafayette and Lehigh in which each side lobbed accusations of improprieties at the other, and both defending their accused athletes — including Barclay.

“The football games to be played between Lafayette and Lehigh are off,” professor F.A. March Jr. told the newspaper. “Lehigh has refused to play if Lafayette plays Barclay and Lafayette, though confident of an easy victory without him, will stand by her crack player and Captain.”

Barclay was a little more than a week removed from a dominant individual performance in the win over Penn, during which both his play and the contraption on his head garnered media attention.

Though it looks like a comedic fake Groucho Marx nose in the below Inquirer cartoon, the piece on Barclay’s animated face is a piece of headgear that functioned as an early version of the football helmet.

Barclay is believed to have been the first player ever to don any form of helmet.

The irony of Lehigh focusing its energy on Barclay and his baseball exploits is that Fielding Yost — later the legendary head coach at Michigan — functioned as a straight-up mercenary for Lafayette ahead of the Penn.

Dave Revsine’s aforementioned The Opening Kickoff details Yost, who played against Lafayette a week earlier as a member of the West Virginia University team, dropping out of WVU and enrolling at Lafayette to play in the win over Penn.

As transactional and imbalanced as today’s transfer portal might seem, it beats the hell out of a championship contender being able to pluck an impressive opposing player away over the course of one week.

Meanwhile, Lehigh’s accusations weren’t enough to shroud the significance of Lafayette finishing 11-0-1.

Burr McIntosh, a prolific silent-film era actor and alum of both Lafayette and Princeton, penned a national football column that awarded All-Americans4 and declared a national champion.

Though Princeton was his pick at “100 per cent” with Lafayette “75 per cent” worthy of declaring itself champ, McIntosh wrote “[n]obody has struggled more bravely for years than Lafayette and she deserves all of her glory.”

McIntosh also lauded the “Indians,” known today as Carlisle, for an admirably arduous schedule that pit the school against Yale, Penn, Harvard and Princeton.

Despite a stunning loss Thanksgiving Day to Brown at Manhattan Field, 24-12, Carlisle finished its season in triumph.

An 18-8 win over Western Conference…champion?…Wisconsin played at Chicago Coliseum drew more than 12,000 per the Saint Paul Globe5 for what could be described as a forerunner to the modern-day bowl game.

The Ivy League didn’t come together until 60 years later.

Alabama was undefeated at the conclusion of the 1964 regular season and ranked No. 1 before losing the Orange Bowl to Texas. While that’s all well-and-good in that national championships were awarded prior to the bowls in that era, the 1965 Crimson Tide — with a loss and tie in the regular season — claim a national title based on previously undefeated Michigan State losing a 14-12 Rose Bowl Game decision to UCLA.

I have discovered that in this era, the common pronoun reference to universities was female rather than today’s common object pronoun.

McIntosh’s All-American team came together with some reluctance. The actor wrote, “Many writers with choose an ‘All-American’ eleven. In starting to attempt to do the same the utter futility and foolishness of the proposition is simply overwhelming to any but a truly great mind. And yet, I’m going to try to as near as possible.

The Globe attributed the attendance at least partially to rumors of President-elect William McKinley being part of the crowd.