What Once Drove A Wedge Between Army & Notre Dame Unites Them Decades Later

Notre Dame and Army played every year from 1913 through 1947, but concerns over the professionalization of college football ended the rivalry. In 2024, the programs have more in common than not.

Concerns over gambling, football fracturing programs from the university mission, and abusive, overzealous fans are not new. In 1946, they were at the epicenter of a decade-long rift between longtime rivals Army and Notre Dame.

The Black Knights and Fighting Irish meet in Week 13 at Yankee Stadium, and for Army, it’s the biggest installment in the 52-game series since 1958.

The 14-2 Cadets' win in 1958 propelled Army to No. 1 in the Associated Press Poll — a spot the team surrendered after a 14-14 tie to Pitt. That was enough to deny Army its first national championship since the dominant World War II-era squads.

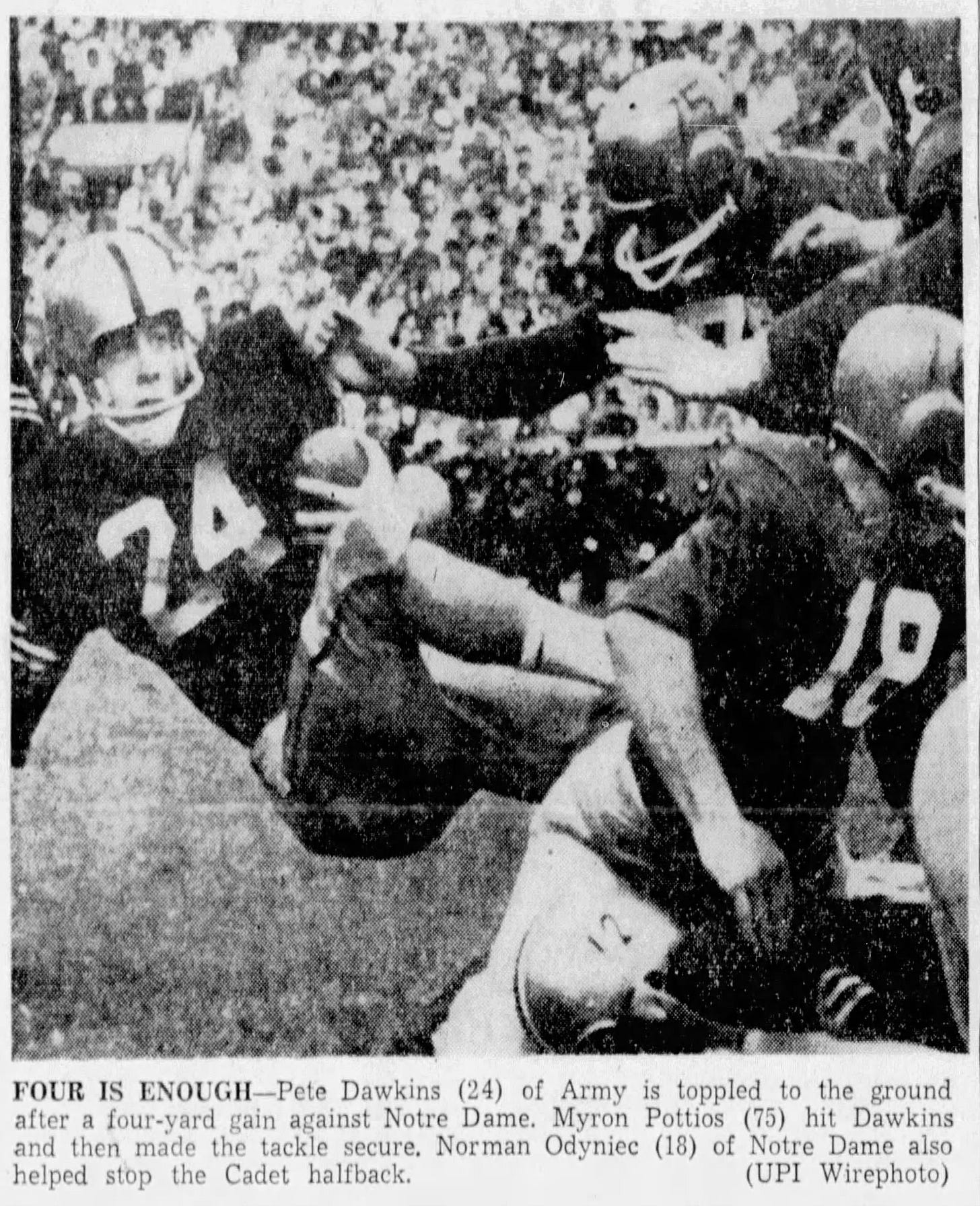

Army running back Pete Dawkins made an impression that remained firmly entrenched in the public’s mind. His starring performance against the Fighting Irish provided a cornerstone for Dawkins’ joining Doc Blanchard and Glenn Davis as a Heisman-winning Cadet.

This was also the last time Army beat Notre Dame.

Although it’s been 66 years, the Black Knights’ losing skid is less overwhelming when evaluated through the lens of it being 15 games. Sure, that suggests history isn’t exactly on West Point’s side when it embarks on The Bronx, with a win or loss meaning the difference between contending for a berth in the College Football Playoff or not.

But there have been repeated hiatuses of varying lengths in a series that was one of the sport’s most high-profile rivalries for more than 30 years in the early 20th century. The fact that the 2024 edition comes after one such hiatus — this one lasting eight years — provides some appropriate symmetry for the era.

Army and Notre Dame in an Uncertain Landscape

The college football world in 2024 looks dramatically different than it did in 2016. The expansion of the Playoff to 12 teams — thus even opening up the prospect of Army qualifying for the field — is among the least drastic changes to the sport over these last eight years.

A virtually unregulated system of Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL) monetization almost immediately became a pay-for-play Trojan Horse. Coupled with an essentially open transfer market, college football now has major American sports' most chaotic version of free agency.

The lack of any institutional oversight could very well untether programs from their universities altogether, turning football teams into professional organizations that use school licensing to function as nothing more than marketing arms. If that seems like an overreaction, consider that Florida State has been actively pursuing private equity partnerships.

Current law prevents such an arrangement between public institutions and private businesses. But with a change in presidential administrations on the horizon, which includes a nominee for Secretary of Education who is, frankly, a monster, don’t expect the federal government to intervene.

College football is on a speed-run toward there being nothing collegiate about it. That’s an element of Army-Notre Dame that gives this game such a unique feel in the modern context.

Army football’s connection to the institutional mission of West Point is the former’s entire identity. Since TV money has reshaped conferences in the last few years — including prompting Army to align with the American Athletic Conference — I have kicked around the idea of an academic-based football league: a national Ivy League at the FBS level.

It would only work as a football-only league, and diving into what it would look like requires a whole other newsletter entry. Suffice it to say, though, West Point would be one of its cornerstone members.

Notre Dame’s status as an elite academic institution, meanwhile, has at times been at odds with its place as a widely recognized football brand. The most recent and prominent example was when Brian Kelly, the Irish’s coach during that 2016 Army-Notre Dame contest, left South Bend for Baton Rouge.

Kelly revealed his motivation for leaving Notre Dame to take the vacancy at LSU was that UND had a different vision than him. The rabid demands of those in the Southeastern Conference, from fans to boosters, were a better fit for Kelly’s pursuits.

Now, there are those who’d contend the win-at-all-costs mentality in the SEC is toxic and increasingly incongruous with what should be the primary pursuits of colleges. I am one such person, and I acknowledge the irony and potential hypocrisy as someone who has covered college sports professionally.

In that regard, I guess I’m like Notre Dame. See, it was Notre Dame’s dogged pursuit of establishing itself as the preeminent college football program post-World War II that caused the original rift between the Fighting Irish and Army.

The End of the Army Dynasty and Notre Dame’s Continued Rise

From the beginning of the 1944 season into November of 1946, Army West Point won 25 consecutive games. The Black Knights didn’t surrender a point in 12 of them.

When their winning streak ended in 1946, the Cadets again didn’t give up a score. But, in failing to score itself, Army lost to Notre Dame in a 0-0 tie.

Wait…lost?

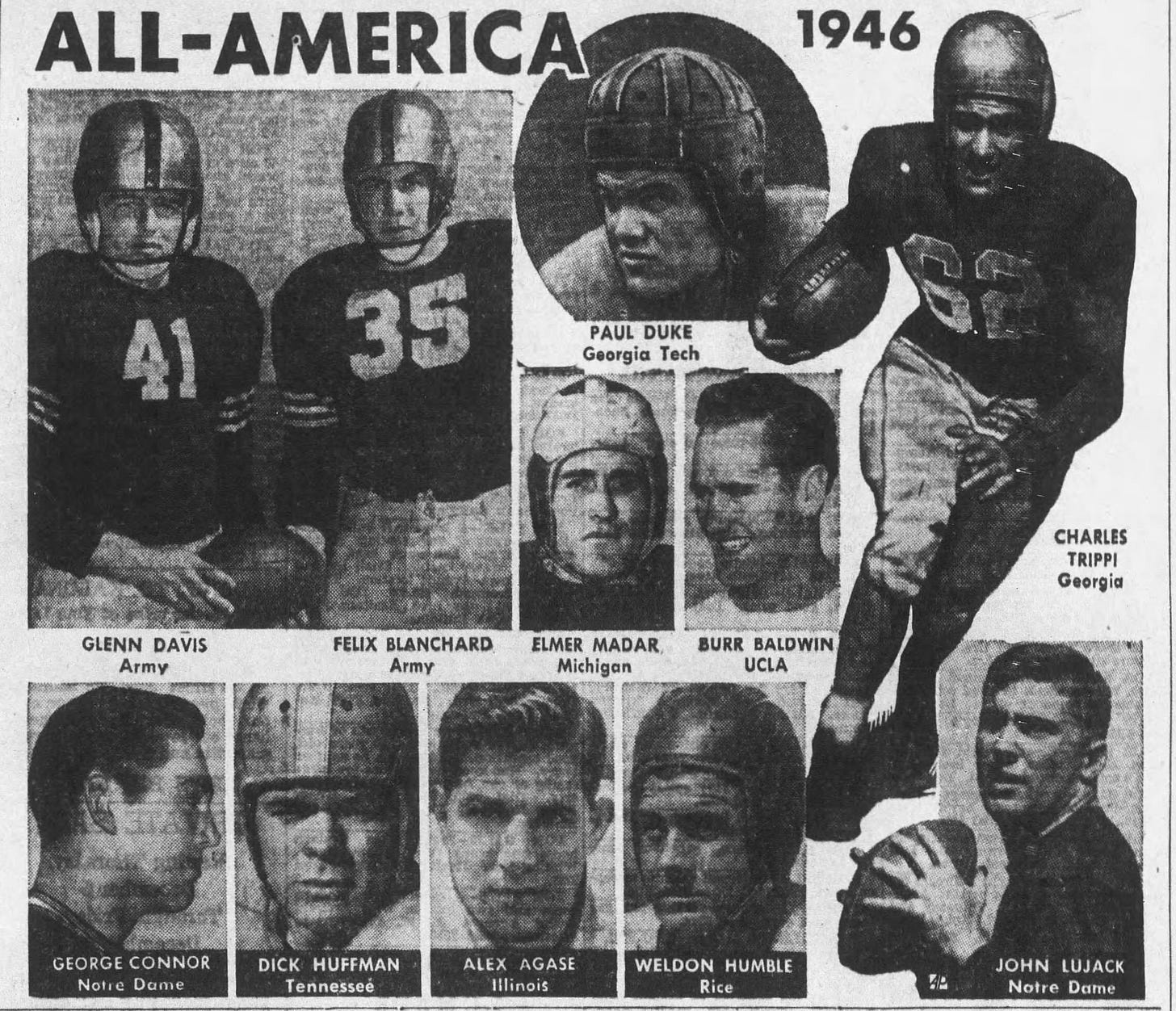

You read that correctly. Army drilled Notre Dame during the Black Knights’ two national championship seasons by scores of 59-0 and 48-0. So, when the Fighting Irish played the Cadets to a scoreless stalemate in 1946, that was perhaps an impressive enough turnaround to justify Associated Press pollsters voting Notre Dame the season’s national champion.

To its credit, Notre Dame followed its tie with Army by shutting out Northwestern and Tulane before drubbing No. 16-ranked USC to close the season, 26-6.

However, Army closed out 1946 with a 34-7 pasting of No. 5-ranked Penn on the road. The Cadets scraped by rival Navy in what was decidedly a down year for the Midshipmen. The post-War attrition took its toll in Annapolis much sooner and more profoundly than it did in West Point, with Navy losing eight straight after a season-opening win over Villanova.

Still, rivalry games often inspire spirited performances from an underdog side with nothing to lose. Could that really be enough to cost Army the sport’s first three-peat since Minnesota a decade earlier?

The answer, of course, was yes. And there hasn’t been an official1 three-peat champion since.

If ever there was a case for a split national championship, this was it. In its own, small way, this decision may have been the proto argument for those in favor of a playoff of some sort.

Meanwhile, with the exception of the 1958 season, the ‘46 Cadets represented the last hurrah of West Point as a national football powerhouse.

Notre Dame, meanwhile, was solidifying itself as the powerhouse of a new era.

The Fighting Irish were well-established as a national brand long before the post-War years. Grantland Rice’s iconic Four Horsemen article ran in the New York Herald-Tribune and via syndication 22 years before the 1946 season.

But in the economic boom following World War II and a rapidly evolving media landscape, Notre Dame football positioned itself to ascend to unprecedented heights.

The Irish’s unprecedented contract with NBC came 45 years later, but it’s fair to argue the seasons immediately following the War sent Notre Dame on that path. The powerhouse teams under Frank Leahy and Ara Parseghian created generations of Fighting Irish fans, building a mystique that made Notre Dame football marketable in ways no other program has approached, even amid the 21st century TV-revenue bonanza.

After playing every season predating even the first World War, the series beginning in and going uninterrupted from 1913 on, the Black Knights and Irish took the next decade off.

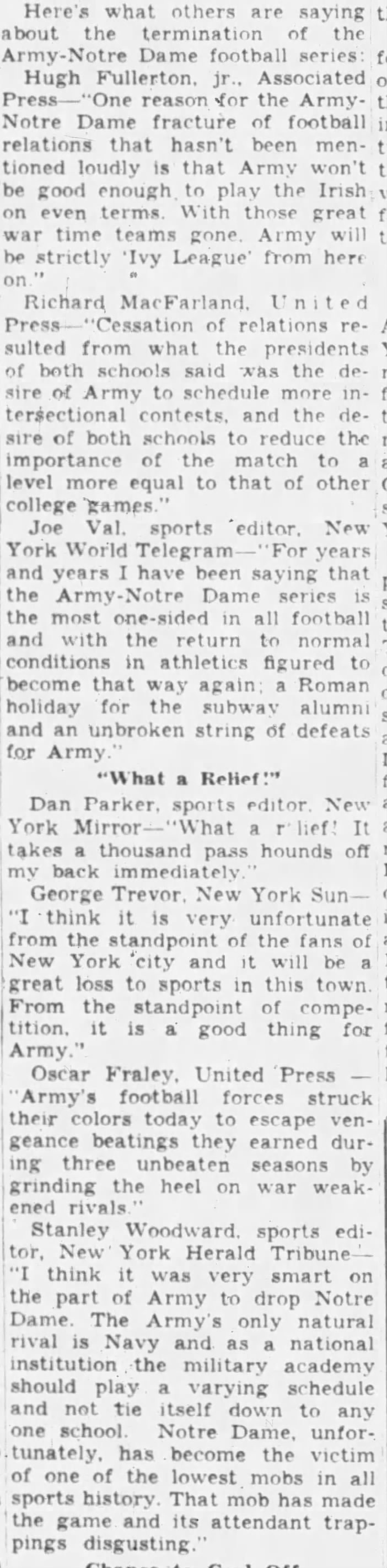

Despite their even make-up in 1946, a roundtable of reporters questioned by the South Bend Tribune in December of that year predicted that the Army and Notre Dame programs’ drift would be a chasm in no time.

The above article touches on a variety of issues contributing to the rivalry’s fraction, but the last line — “That mob has made the game and its attendant trapping disgusting” — alludes to a matter of present-day relevance: Gambling.

The two sides playing in New York is an overture to Notre Dame’s Subway Alumni; the diehard Fighting Irish fans from the city who never attended the South Bend school. New York in this era became a hotbed, or maybe cesspool is the better term, for illegal sports gambling. It’s worth noting that this was the same period in which rampant bookmaking on the courses at Madison Square Garden led to the biggest scandal in college basketball history as well as the NCAA Tournament avoiding The World’s Most Famous Arena for six decades.

One report from the 1946 Notre Dame-Army game estimates a half-million dollars changed hands among bettors that day, no small sum in the context of the time.

A college football landscape in which point spreads are included on TV graphics, broadcasters openly reference betting implications and a university athletic department partnered with a sportsbook stands in a dizzyingly stark contrast.

Indeed, the two worlds of the post-War Army-Notre Dame rivalry and today’s renewal of the series are unrecognizable. But some of those quoted sportswriters in 1946 saw elements of it coming.

The programs played one more time in the ‘40s, and predictions of Notre Dame turning the tables on post-War Army proved prophetic in 1947 when the Fighting Irish won a 27-7 rout in South Bend.

That kicked off a run that continued in 1957 and extends into 2024: 17 Notre Dame in 18 tries. Notre Dame did indeed become the powerhouse while Army, perhaps not so much an “Ivy League” program as the AP’s Hugh Fullerton projected, became one of the closest things to the Ivies among major college football.

Perhaps the most surprising part some 80 years later is how much closer the Army and Notre Dame programs of today might be within the broader context of the sport.

Assorted publications and polls ranked Army No. 1, giving the program claim to a championship. The AP title was the official championship of the time, however.