What If Wednesday: Willie Mays and The Legacy of The Negro Leagues

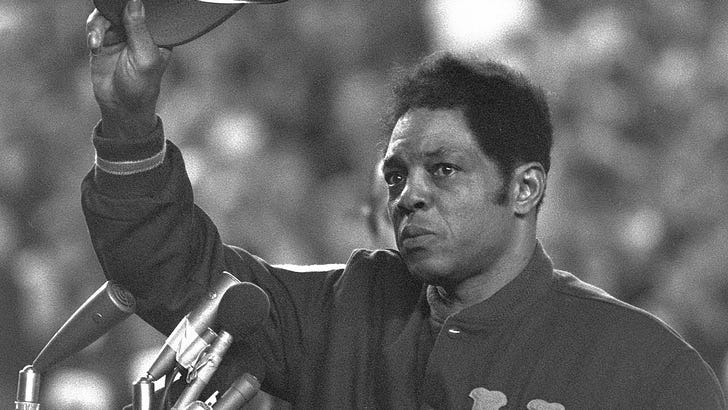

“The Say Hey Kid” Willie Mays said goodbye on Tuesday at age 93, leaving behind a well-earned reputation as one of baseball’s true legends. Legend is one of those terms in sports used somewhat cavalierly — I know I’m guilty of it — but the label undeniably applies to Willie Mays.

Mays is a surefire choice for any all-time roster of the game’s greatest to ever do it. His run of All-S tar Game starting nods in 10 consecutive seasons and 12 straight Golden Glove campaigns are both tied for fifth-most ever. The perhaps more impressive testament to Mays’ longevity is that his two Most Valuable Player awards came 11 years apart: 1954 and 1965.

Those MVP accolades crossed two of the four different decades in which Willie Mays played professional ball. However, due in part to organizations’ continued resistence to integration even after Jackie Robinson’s debut in 1947, Mays’ Major League career spanned three decades.

Willie Mays first premiered in MLB in 1951 and was an immediate sensation, earning National League Rookie of the Year with a .274 batting average and more home runs (20) than strikeouts (17).

Remarkably, Mays’ Rookie of the Year award-winning season was his last full MLB campaign before his MVP-winning 1954 campaign, the result of his enlisting for service during the Korean War.

This is purely anecdotal, but based on my own experiences Willie Mays’ military service seems to be presented as more of a historical footnote than it is woven into the fabric of his legacy a la Ted Williams. Certainly they had much different experiences, with Williams serving in both World War II and Korea, and Teddy Ballgame having established a reputation for his abilities as a Marine pilot.

Willie Mays did not see combat in the Korean War. Still, his enlistment branches off into other fascinating topics that intersect with Mays’ overall imprint on baseball history.

First and most obvious for a What If Wednesday entry is how losing almost two seasons impacted Willie Mays’ standing in the career home-run rankings.

Mays hit 660 Major League home runs, currently sixth-most in history with it appearing unlikely any active player will catch him. Giancarlo Stanton is closest with 419 as of this writing on June 19.

And while Stanton’s 17 thus far in 2024 puts him on his best pace since hitting 59 in 2017, he would need to play a minimum of eight more seasons producing at his career average of roughly 29 a season to catch Willie Mays.

That speaks to just how staggering Mays’ home-run production is, and that’s before considering he missed out on essentially five seasons of Major League play from 1948 until his 41-homer campaign of 1954.

Say Mays completed the 1952 season at the pace he was on — four home runs through 34 games — playing a minimum of the 151 games in which he appeared every season from 1954 through 1966, he finished right around the 20 mark reached as a rookie with the New York Giants.

Splitting the difference between 20 home runs and the jump he made to 41 upon returning from active duty, adding 30 homers in 1953, Mays remains ahead of No. 5 all-time Alex Rodriguez and No. 4 Albert Pujols.

He’s also very much in the hunt to surpass Babe Ruth’s 714 by the end of Mays’ career in 1973, the season before Hank Aaron set the mark.

Alternatively, Mays returns for one last season in a 1974 season kicked off with he and Hammerin’ Hank chasing Babe, and we are commemorating the 50th anniversary of an irreplicable moment in sports history to celebrate Willie Mays’ life.

Of course, the prevailing sentiment about Mays’ final season in 1973 is that it’s the quintessential example of a legend holding on too long. “Willie Mays as a Met” is often the first reference made when comparing present-day instances of fading stars playing below standard for organizations other than those where they made their name.

These instances of sports history are sometimes not as bad as they’re presented. Michael Jordan averaged 23 points, 5.7 rebounds, 5.2 assists and 1.4 steals as a Wizard in 2001-02, and 20 points, 6.1 rebounds and 1.5 steals per in 2002-03, for example. Emmitt Smith rushed for nine touchdowns and 937 yards with the 2004 Arizona Cardinals.

And, upon his trade from the San Francisco Giants to the Mets in 1972, Mays rebounded from a sluggish start by the Bay to hit .267 and produce a .402 on-base percentage with eight home runs over his 195 at-bats in New York.

He even homered in his first at-bat as a Met.

Yes, The Say Hey Kid’s 1973 season was forgettable with a .211 batting average in just 66 games played. But it is worth noting his time in Flushing wasn’t all bad.

Like the aforementioned Michael Jordan, though, the standard set was just so remarkably high that a noticeable decline becomes much more pronounced compared to other players.

All that is to say, perhaps Willie Mays and Hank Aaron having a home-run chase at the beginning of the 1974 season would not have been as compelling as I imagine it — especially given that Aaron knocked out 40 more over nearly three seasons after surpassing Ruth.

Further, Willie Mays received an almost storybook send-off in 1973, culminating in an emotional farewell speech at Shea Stadium shortly before the Mets advanced to the World Series.

Nevertheless, a Willie Mays-Hank Aaron home-run showdown is an interesting scenario to imagine — and another example of why baseball’s recent embrace of Negro League history is so long overdue.

Both Mays and Aaron played in the Negro Leagues before beginning their Major League careers. Mays spent three full seasons in the Negro Leagues before debuting with the New York Giants, playing for the Birmingham Black Barons from 1948 through 1950.

The Black Barons played at Rickwood Field, which on June 20 hosts a Major League game between the St. Louis Cardinals and San Francisco Giants. That the organizations in which Willie Mays began his professional career and where his legend grew are both represented, on the same week Mays died, is an especially serendipitous aligning of stars in service of the game’s purpose.

MLB is finally using its prominence in American culture to promote chapters in the game’s history that for too long were ignored. Overlooking Negro Leagues history for so long is reflective of a deeper issue our society as only recently started to acknowledge, which came up in my household this week.

My oldest child asked my wife and I about Juneteenth. This led us into discussion about the Tulsa Massacre, a hinge event of 20th Century American history that I only learned about for the first time in 2019.

Realistically, addressing things like the Tulsa Massacre, the Trail of Tears and the Wounded Knee, and even the segregation of baseball requires some gut-wrenching introspection few are ready for. The progress made over the last few years is significant, but there remains plenty of work to be done.

MLB’s decision to acknowledge Negro League statistics in career records, announced this year, is a meaningful gesture but still something of a half-measure. For example, the hit five home runs Hank Aaron with the Indianapolis Clowns are not part of his official total.

Josh Gibson did not become the new home-run king in the record books, despite being widely believed to have hit more than 800 in his Negro League career.

Willie Mays’ statistics from a 1948 season in which he helped the Black Barons reach the Negro League World Series count toward his professional records. He is reported to have made spectacular defensive plays that may have been harbingers for his iconic catch in the 1954 World Series.

Mays is also rumored in that same autumn to have thrown a 50-yard touchdown pass against Booker T. Washington High School of Pensacola, though the claim in an Alabama Times gossip column is unsubstantiated.

Likewise, Mays’ exploits in the Negro Leagues during the 1949 and 1950 seasons — during the latter of which he was rounding into the form that earned him NL Rookie of the Year in 1951 — are treated with the same veracity as his touchdown pass by official MLB stats.

So where might Willie Mays rank all-time for home runs if the entirety of his Black Barons numbers counted to his totals? Or, better yet, where might he rank if he’d been in the Major Leagues for those two seasons, along with most of 1952 and all of 1953 when he served?

In some regards, the latter is the most interesting to evaluate in a historical context — and not just because Mays was on his way to becoming the superstar we know today once he was drafted, but more for how his service deserves more consideration in Mays’ legacy.

In summer 1948, when a teenaged Willie Mays still finishing high school debuted for the Black Barons, Pres. Harry Truman signed Executive Order 9981. This action desegregated the Armed Forces.

To that end, Willie Mays is a unique pioneer who was involved the early phases of two American institutions making pivotal moves toward intergration.

Negro Leagues Museum president and baseball historian Bob Kendrick, whose segments on the video game MLB: The Show provide some of the most insightful commentary on Negro League historian I have ever consumed1, once said that MLB including Negro League stats for the purpose of records like Mays and Aaron’s home runs wasn’t necessary.

“They knew how good they were and they knew how good their league was. So they never sought validation from anyone,” columnist Berry Tramel quotes Kendrick.

More important than any statistical rankings is celebrating who these players were and why their legacies matter.

I am planning a video on my seldomly used YouTube channel to highlight MLB: The Show’s terrific Negro Leagues features.