What If Wednesday: Bill Walton, Donald Sterling & The Failure of The San Diego Clippers

Long the little brother of Los Angeles basketball, the NBA’s Clippers make an unprecedented play to carve out their own portion of the city in 2024 with the opening of the Intuit Dome.

Sure, the opening of the new arena won’t mark the first time that the Clippers had their own home in Los Angeles. However, anyone who experienced the Sports Arena can tell you that being the third-most prominent tenant at Staples Center1 and having to banner over the downtown venue’s many monuments to Lakers greatness is a much homier experience than having sole dominion over the dank, poorly lit Sports Arena.

But even the Clippers’ exclusive home court comes with reminders that L.A. is a Lakers Town. The Inuit Dome is in Ingelwood, within walking distance of the arena f/k/a The Great Western Forum.

The Forum still stands, having undergone refurbishing not long before the Rams moved into SoFi Stadium across the street. While it primarily hosts concerts today, it’s impossible to see the Forum’s distinct facade and not immediately think of Magic, Kareem, and the single-most transformative team in NBA history.

The Los Angeles Sports Arena, which was demolished in the latter-half of the 2010s to make room for LAFC’s home BFO Stadium, has a kindred spirit in the San Diego Sports Arena. LA Sports Arena opened in 1959, just seven years prior to San Diego’s similarly named venue.

Known today as Pechanga Arena, the venue is still quite active. The American Hockey League’s San Diego Gulls and Indoor Football League’s San Diego Strike Force play there, big-name musical acts routinely pass through, and it routinely hosts pro wrestling, MMA and boxing.

Despite its age, it’s really not a bad venue. At least, it’s been more well-maintained up to present day than L.A. Sports Arena was even back in the ‘90s. The San Diego Sports Arena is also a far cry from being up to NBA standards, and its continued presence just south of SeaWorld and on the road toward Point Loma stands as a reminder of the city’s failed NBA aspirations.

San Diego has a reputation as a fair-weather sports city, but that’s not entirely accurate. San Diegans show up and are passionate if presented with a quality product. Since A.J. Preller became Padres general manager, and with Peter Seidler’s investment into the franchise before his death last November, Petco Park has buzzed with unbridled enthusiasm.

Likewise, San Diego State’s basketball ascent from Mountain West Conference bottom-feeder to Final Four-caliber program ignited genuine passion for the Aztecs far outpacing its Southern California counterparts — including the most decorated program in college hoops history, UCLA.

Viejas Arena is a beautiful, on-campus venue and such a quintessential college basketball spot, it hosts NCAA Touranment games every four years or so. The arena rocks for SDSU home games, and in a cruel twist of irony, offered Clippers owner Steve Ballmer a blueprint for how he wanted Intuit Dome to be structured.

I have long wanted to produce a deep dive on San Diego’s cursed pro basketball history. I don’t know if it would make good material for a book, but if it was presented in such a fashion, the majority of the chapters would be dedicated to the Clippers.

And that’s not exclusively because the Clippers lasted longer in San Diego than their predecessors the Rockets or the ABA’s Conquistadors/Sails. So much of that validates my use of the word cursed to describe San Diego’s forays into pro hoops revolves around the mismanagement and bad luck surrounding the Clippers.

Like so many other episodes in sports history, the short answer to why the San Diego Clippers failed comes down to money.

The Sports Arena’s2 never been replaced by a more modern venue up to NBA standards for the same reason Dean Spanos opted to turn the popular San Diego Chargers into the Los Angeles Chargers, e.g. the NFL’s Clippers: A little brother in their own city and renter in someone else’s home stadium.

In the case of building new venues, ownership groups have come to the public with Jerry Lundegaard-inspired proposals. It’s gone as well for the owners with voters as Jerry’s pitch went over with Wade Gustafson.

And, like the Chargers with Spanos, the Clippers’ fate in San Diego was likely unavoidable due to ownership. Original San Diego Clippers owner Irv Levin, who bought the franchise in 1978 with the intention of moving it from Buffalo, sold just three years later to attorney-turned-land baron Donald Sterling.

The timing of this edition of What If Wednesday is doubly apropos. It drops less than a week ahead of the premiere episode of Clipped, the FX miniseries about Sterling’s disastrous leadership.

The Clippers Curse really begins with Sterling. Though the organization wasn’t setting the world on fire in Buffalo or for the short period Levin owned it, the Braves reached the Playoffs three times under coach Jack Ramsay, including in Bob McAdoo’s MVP-winning 1975 campaign.

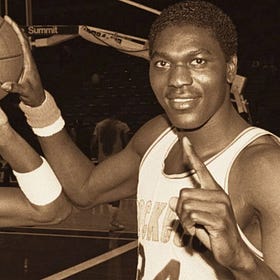

In the franchise’s first year as the Clippers, the team went 43-39 playing one of the most exciting styles in the NBA. World B. Free averaged almost 29 points per game while backcourt mate Randy Smith — an All-NBA honoree in 1976 — went for 20.5 points, 4.8 assists and 2.5 steals a contest.

The 1978-79 Clippers showed promise but needed a big man. Enter Bill Walton.

A graduate of Helix High School in the La Mesa community of south-central San Diego County, Walton is a legend in America’s Finest City. He ranks alongside Tony Gwynn as a no-doubt inclusion on a proverbial San Diego sports Mount Rushmore.

Signing Walton in the 1979 offseason, two years removed from Big Red winning MVP, was also a no-brainer move for Levin and the Clippers front office. The only uncertainty was the foot injury that sidelined Walton for the duration of Portland’s 1978-79 campaign.

The potential reward for adding Walton was sky-high, and the Clippers’ most ambitious offseason move until Kawhi Leonard’s signing 40 years later. Unfortunately, it didn’t pay off.

Walton played only 14 games in the 1979-80 season. The two-month stretch from late January to mid-March 1980 was the last time he’d see the floor until October 1982.

For me, Bill Walton’s entire NBA career ranks among the most compelling What Ifs in the league’s history along with those of Ralph Sampson, Arvydas Sabonis and Grant Hill. Focusing exclusively on his ill-fated homecoming to San Diego may separate Walton’s arc as the most impactful of the quartet.

The Clippers’ success (or lack thereof) under Donald Sterling was immaterial to the franchise moving north. Sterling wanted to be in Los Angeles, period.

However, there’s an interesting alternate reality to envision with an Irv Levin-owned Clippers succeeding if Bill Walton returned to the court healthy and performing near his 1978 level.

With World B. Free averaging more than 30 points per game, the ‘79-’80 Clippers finished 35-47. The next season’s 36-46 was the best any Clippers team would finished for more than decade until the 1991-92 squad went 45-37.

Pairing the dynamic perimeter scorer Free with a steady interior presence in Walton during the ‘79-’80 campaign would arguably have gotten the Clippers over the hump and into the Playoffs. Walton’s former team, the Blazers, qualified at 38-44, so it’s hardly presumptuous to suggest that with a healthier Walton, San Diego would have easily surpassed that mark.

How that may have impacted roster structure going forward requires extensive untangling. San Diego traded World B. Free in the 1980 offseason, a move that sent him to Golden State for former two-time All-Star Phil Smith — coming off his own struggles with injury — and a 1st Round pick in 1984.

It’s well-established that the 1984 draft class was loaded, so having two first-round selections that year was a good thing. At least, it could have been. The Clippers took Michael Cage at No. 14, adding another prominent San Diego figure.

What If Wednesday: Reimagining The Transformative 1984 NBA Draft

The NBA draft has always been a summer highlight for me. Maybe that’s a byproduct of growing up a San Antonio Spurs fan and remembering how transformational the 1997 draft lottery proved for the organization. But even before Tim Duncan fell into the Spurs’ laps 27 years ago, and in the subsequent years when San Antonio was well removed from the lottery,…

Cage ranks among the all-time best San Diego State players in program history and played a few promising NBA seasons in the late ‘80s.

Unfortunately, the 1984 preceded the Clippers’ move to Los Angeles, so the local college star never played professionally in his university’s city.

Meanwhile, the Clippers selected Lancaster Gordon at No. 8 with the pick acquired for trading Free. His selection came just ahead of future All-Star big men Otis Thorpe and Kevin Willis.

The Louisville product Gordon started six games in four NBA seasons.

In other words, the Free trade could have been a bonanza for the Clippers — but it wasn’t. So perhaps keeping a corps with Free and a healthy Walton beyond 1980 changes the Clippers’ roster structure going forward, but does so for the better.

If nothing else, the local star Walton making a triumphant return to the hardwood and taking San Diego to the Playoffs generates hope; the prospect for the city breaking out of the basketball doldrums experienced in the prior decade with the Rockets leaving after just one season, and the NBA successfully litigating Wilt Chamberlain out of ever suiting up for San Diego’s ABA franchise.

Had that been enough to prevent Levin’s sale in 1981, or perhaps changed ownership to someone other than Donald Sterling, perhaps it’s enough to alter the entire trajectory of the Clippers franchise from that of L.A.’s little brother to a beloved member of San Diego a la baseball’s Padres.

I don’t have issue with corporate-sponsor arena names; Staples Center was one, after all. However, much like my stance on the social media app I no longer use and its idiotic rebranding by a charlatan, I refuse to refer to the former Staples Center by its current name because of what the rebrand implies.

Case in point, the most recent Sports Arena proposal originally came with a promise of developing middle-income housing, addressing a serious issue for San Diego County amid skyrocketing home prices. Midway Rising, the group behind the proposal, went back on that part.