Victor Wembanyama, Zach Edey and The Ballad of the Big Man

From the moment James Naismith first nailed a peach basket to the balcony at the Springfield YMCA back in 1891, height ruled basketball.

And, for all the buzz in recent years of positionless basketball shifting emphasis to it being a guard-oriented game, reality is that it’s still a big man’s game.

Compiling research for the College Basketball 101 really underscored for me just how dominant big centers were throughout NCAA history. It makes sense: The goal being 10 feet off the ground, a closer starting point to the desired destination just works.

Introduction of the 3-point shot provided more scoring opportunities for perimeter players, though the shift to heavy emphasis on the triple was a slow, 30-year stroll into a five-year sprint.

The analytics-fueled change in philosophies, wherein the 3-pointer went from a specialized tool in a wider offensive arsenal to the foundation of entire offenses.

Four different guards won five consecutive NBA Most Valuable Players from 2014-18, an unprecedented stretch in league history. Guards swept the assorted college basketball National Player of the Year awards over a similar stretch from 2016 through 20181, also an unprecedented run2.

Four of the five NBA MVPs measured 6-foot-5 or shorter; none of the college Players of the Year were taller than 6-foot-4.

Basketball media was quick to tell us big was out. Like the dinosaurs, the massive went extinct from a meteor launched beyond a 3-point arc and a smaller apex predator roamed the earth.

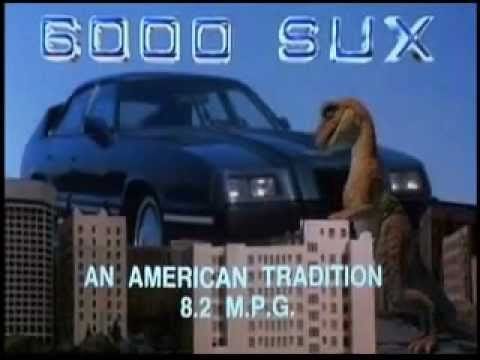

Well, dear reader, I’ll defer to the following bit from my all-time favorite film, RoboCop, which summarizes the current state of the game.

Tonight is NBA draft night and a yearlong (or longer) inevitability comes to fruition when the San Antonio Spurs select Victor Wembanyama first overall.

The Texas-bound French import Wembanyama’s steady march to the No. 1 overall pick was paved with Reels and TikToks and written accounts of his vast skill set; his ability to handle the ball, his court vision, his leaping ability and his shooting range.

But none of those skills matter — at least, they matter significantly less — if Wembanyama wasn’t really, REALLY tall.

OK, so that seems like a No Duh statement since I’m talking about a basketball player. But I mean Wembanyama is exceptionally tall even in basketball terms. Just how tall is up for some debate.

I first saw him listed at 7-foot-2, have read accounts that he’s 7-foot-9 — which would make him two inches taller than the most vertically gifted player in NBA history, Gheorge Muresan — and see him commonly referred to as 7-foot-5 on social media.

He’s sort of the Dorian Grey painting of Nate Robinson, the former Washington Huskies star and New York Knicks reserve whose exploits as a standout dunker led to him “shrinking” from 5-foot-10 to approximately No Bigger Than His Father’s Thumb.

For brevity’s sake, let’s say Wembanyama is 7-foot-4. That’s tall, even for professional basketball standards. It’s especially so for a hooper whose highlights include a multitude of perimeter plays, dribbling around defenders and firing from beyond the arc.

It’s natural to observe Wembanyama’s highlights and see him as the next evolutionary step in the sport, one in which the sport is played entirely from the outside-in.

Dirk Nowitzki, one of the headliners in this year’s absolutely stacked Basketball Hall of Fame class, was a forerunner in the sport’s shift to a more perimeter-oriented style.

Right in the neighborhood of 7-feet, Nowitzki came into the NBA in an era when players of his size almost exclusively occupied the paint with their backs to the basket offensively.

Even the new wave of lengthy power forwards with face-up skills who came a few years prior to Nowitzki’s draft selection to the Dallas Mavericks — fellow Hall of Famers Tim Duncan and Kevin Garnett — operated from the high-post. A 7-footer who stepped up beyond the 3-point line was almost unheard of before Nowitzki (emphasis on almost. Keep that in mind for later).

“Dirk started all that mess and now everybody’s shooting 3s now, nobody’s going inside anymore. Thank you, Dirk,” former San Antonio Spurs guard Tony Parker deadpan quipped to Nowitzki, getting a chuckle out of his former rival and fellow 2023 Hall of Fame inductee.

Many a truth said in jest, as the cliche goes. By playing out on the wing and shooting the 3-pointer at a clip of more than three per game3 and 38 percent for his career, Nowitzki set a precedent to ensure the future of the big man.

Wembanyama projects as the next wrinkle following in the precedent Nowitzki established.

“He’s a freak. Unbelievable,” Nowitzki said of Wembanyama. “You always think you’ve seen it all during your life and your career and history of the league, and then somebody else comes along. Kevin Durant comes along, a 7-[foot]-2 two-guard, now we have a 7-[foot]-4 two-guard.”

Something that struck me as interesting was that, while Nowitzki labeled Wembanyama a “7-4 two-guard,” Parker referenced four Hall of Famers to describe the youngster; three of whom played a more traditional tall-guy style.

“He can be one of those guys [who] can have a career like Timmy [Duncan] or KG [Kevin Garnett] or Dirk or Pau [Gasol],” Parker said. “He has all those abilities.”

That’s a fascinating group to draw parallels to, considering that draftniks (professional or wannabe) have focused on Wembanyama’s perimeter play. Yet, Parker — owner of the ASVEL club for which Wembanyama played in 2021-22 — has perhaps a more intimate perspective on the future Spur’s potential than anyone else.

The Durant comparison Nowitzki offered up is the most common, but only with the hindsight we have from Durant’s outstanding career.

His selection at No. 2 in the 2007 NBA draft often gets cited as one of the all-time great blunders, with the Portland Trail Blazers instead taking Greg Oden No. 1 overall. I reject this suggestion on multiple fronts, one of which being I firmly believe had Greg Oden been healthy, he would have been a star.

He entered into the NBA at a time when the specific skill set of a player his size was particularly valuable, drafted two years after Shaquille O’Neal played at an MVP level and year after Shaq helped the Miami Heat to a championship; taken the same year Tim Duncan won his fourth title with San Antonio; and during the rise of Dwight Howard, who guided Orlando to the 2009 Finals (and should have won 2011 Most Valuable Player).

What’s more, it’s typical of sports commentary to latch onto the negative of a topic like this — in this case, Oden failing to make an impact in the NBA — rather than praise exceptional performance.

Durant’s star turn was the result of exceptional strategy. It’s worth noting that Durant, despite shooting a lot of 3-pointers in his one season at Texas, ostensibly played power forward. And he was excellent at it — in college.

Kevin Durant would not have been an effective NBA power forward. Recognizing this and playing the 7-foot Durant as a guard when he succeeded P.J. Carlesimo as Oklahoma City Thunder coach in 2008 was a stroke of genius by Scott Brooks that, while it seems obvious in retrospective, was a bold decision in the era.

Of course, not every 7-footer has the skill set of a Kevin Durant — really, Dirk Nowitzki may be the only before and Wembanyama may be the only since. But tailoring the strategy to the player and not attempting to fit the player into a strategy should be the key takeaway.

I remember my dad, a longtime teacher of the game, saying simply, “You can’t coach height.”

No matter if Wembanyama’s game is the next incarnation of the Durant style, where he’ll be a two-guard, or he shows the ability to score consistently at the elbow like Duncan and crash the glass like Garnett, he’s the most coveted No. 1 pick since LeBron James4 because he’s really, really tall.

And, he’s entering into an NBA where the last five straight MVPs were tall guys.

Each of the past three MVPs went to a pair of centers in Nikola Jokic and Joel Embiid. Although neither is a center in the way Kareem Abdul-Jabbar or Patrick Ewing or even Dwight Howard was a center, both have reemphasized that basketball’s a game that still belongs to the big guy.

2019 and 2020 MVP Giannis Antetokounmpo may not play center, but at about 6-foot-11 with a style reminiscent more of David Robinson in his heyday than of Kevin Durant, he’s also indicative of big men reclaiming the mantle of the sport.

Speaking of David Robinson, that brings us to our last case study: Zach Edey.

Edey was a runaway and unanimous choice for National Player of the Year, making him the fourth power forward or center to sweep the college basketball honors in as many years.

The comparison to Robinson comes from Edey’s national rank in scoring, rebounding, shot-blocking and field-goal percentage, finishing the season 21st or better in each category for the best all-around individual campaign since The Admiral in 1987.

I asked Edey during the presentation of the Oscar Robertson Player of the Year award about the parallel to Robinson.

“It’s crazy whenever your name gets mentioned with a Hall of Famer’s,” he said. “Basically, he did everything you could in the league; he won the Finals, he won MVP.”

Now, Edey’s specific style of play isn’t comparable to Robinson’s; not offensively, at least. The shot-blocking and rebounding prowess have similarities.

But to be as productive as Edey was, and that no other big man for almost four decades didn’t match the same across-the-board output — four decades that produced all-time college centers like Shaq, Marcus Camby, Emeka Okafor and Tim Duncan — has to carry weight.

Edey is returning to Purdue coming off a shocking NCAA Tournament. It’s possible the Boilers’ 1st Round loss to Fairleigh Dickinson is a red flag; Deandre Ayton’s 2018 Arizona team lost a similarly ugly opening-round contest to Buffalo, a game that foreshadowed some of the struggles Ayton’s had since being the No. 1 overall pick to Phoenix.

The Ayton selection over Luka Doncic, a likely future MVP, came at the end of the five-year guard monopolization of top individual. Doncic’s immediate success and Ayton’s confounding inconsistency would seem to reinforce the idea it’s become a guard’s game.

And yet, for as publicly as Ayton’s struggled, he was also absolutely instrumental to Phoenix reaching the NBA Finals in 2021 with stat lines not seen since Shaq. That stretch only makes Ayton’s uneven play all the more frustrating, because he’s shown he can be a linchpin.

I am eager to see how Edey continues to develop. He’s a full four inches taller than Ayton, making Edey the same height as Wembanyama.

I suspect Edey will make some noise this time a year from now because, as much as the game’s changed, a constant reality is you can’t coach just any productive player to be 7-foot-4.

Frank Mason III and Jalen Brunson swept the assorted awards in 2017 and 2018, and while Buddy Hield didn’t sweep in 2016, the one he lost out on went to another guard in Denzel Valentine.

Guards Jay Williams, T.J. Ford and Jameer Nelson won National Player of the Year honors in 2002, 2003 and 2004, respectively, but Williams split one of the awards with Kansas power forward Drew Gooden; Ford shared honors with David West and Nick Collison; and Emeka Okafor denied Nelson a sweep of National Player of the Year.

A high figure for the era in which Nowitzki played most of his career; consider that Reggie Miller, regarded largely as a 3-point specialist, attempted 4.7 per game for his career, or that even Steph Curry attempted fewer than five a contest until 2013, it’s safe to assume Nowitzki’s 3-and-change for his career would be closer to 5-6 today.

Although “just” 6-foot-8, James is a physical anomaly in a different sense with his combination of burst, speed and athleticism in the frame of a Pro Bowl tight end.