The Press Break Q&A: Conference Tournaments, State of the Washington Huskies, Forbidden Door and More

You’ve got Qs, The Press Break has As. Welcome to another edition of this fine quasi-weekly column in which I take YOUR questions and do my best to provide worthwhile answers. And if I don’t have an answer, well, I’ll find a tangent to go off on.

Let’s get started!

Every Tournament seems to produce at least one of these teams, not counting a Cinderella from a mid-major conference a la Loyola Chicago. Last year, it was Oregon State; Oregon did it in 2019; and Kentucky nearly won a national championship in 2014 with such a rise.

I like Rutgers as a potential second-weekend team this year. The Scarlet Knights racked up a bevy of quality wins, including at Wisconsin, during the month of February. They play excellent defense and have perhaps the nation’s premier on-ball defender in Caleb McConnell.

There’s no guarantee they make the field due to unfavorable analytical standings — Rutgers is No. 74 in KenPom, for example — but if the Scarlet Knights do get called, they’re dangerous.

Anyone I speak to beyond the realm of The Internet refers to it as March Madness or “the tournament.” Interestingly enough, the former celebrates 40 years in the public lexicon this year, as Brent Musburger first used the label in 1982 (but credited it from hearing it referenced about the Illinois high school basketball tournament, oddly enough).

No matter its origins, it’s an excellent bit of branding and a fascinating topic of conversation in 2022 particular. This is the first year the label will be applied to the Women’s NCAA Tournament as well, and I must admit…I don’t like that.

It’s not because it’s undeserved or anything ridiculous like that, but rather, it would have been cool for the Women’s Tournament to adopt its own branding; Best In Basketball, Spring Spectacular, something that belonged to that event alone.

Easiest call in the world: Fewer timeouts. The flow of late-game situations gets choked off from the bevy of timeouts called. It’s especially grating during March Madness, when pauses are extended for the sake of advertising. Granted that revenue is important, so I’m more than willing to trade off a better, more fluid end-of-game scenario for picture-in-picture advertisements perhaps midway through the halves.

My solution is that each team, regardless of how many they have remaining at the Under-4 media timeout, are restricted to one 70-second and one 30-second timeout each. These cannot be used in succession, either, with calling a timeout out of a timeout resulting in a technical foul.

I have seen a growing call for the Elam Ending1, used in The Basketball Tournament to determine a winner not with a clock but a set final score. The idea that “every game ends on a made basket” is all well and good, and I’m actually a proponent of it in college basketball for overtimes — but not regulation. The game is more likely to improve its late-sequence flow with fewer timeouts than with the Elam Ending.

I have a love-hate relationship with conference tournaments. I understand why they exist, particularly for the conferences that benefit the least (mid-and-low-majors, which receive a substantial and necessary payday from TV outlets). But it’s frustrating seeing a team like Towson bounced out of a bid after playing the best ball in its conference for a month-and-a-half; or having Kerr Kriisa sustain an ankle injury in the 1st Round, playing a team his squad had already between twice in a conference it won by three game.

At the same time, Championship Week is an integral part of the season. You have to take the bad with the good. I also don’t believe any conference needs more than eight teams in its tournament.

Eight is a perfect format. And while I appreciate leagues like the WCC setting up their two best teams in the semifinals, that sometimes backfires. The OVC is a great example, which has seen one of its two auto-semifinalists routinely bounced, coming in rusty against opponents that have had an opportunity to build some mojo and familiarity with the court.

Eight gives you 1 vs. 8, 4 vs. 5, 3 vs. 6, 2 vs. 7. No muss, no fuss. You finish below that line? Sorry, you don’t make the field.

Speaking of conference tournaments…

The first college basketball game I ever attended was in 1988 and the championship of the Pac-10 Tournament between Arizona and Oregon State. I was too young to remember it, but I suppose I observed the energy via osmosis enough to credit that as a launching point for my basketball fandom.

Thirty years later, I covered the Pac-12 title game between Arizona and USC in Las Vegas. That ranks up there for me simply by being physically present at T-Mobile, which was sold out and absolutely rocking.

One of the problems with conference tournaments — and one that the Pac-10/12 struggled mightily with from 2002 through 2012 when it played at Staples Center — is a dead atmosphere. Moving to Las Vegas over a weekend that coincides with the start of spring break for a few of the league’s members was brilliant, and this game encapsulated why.

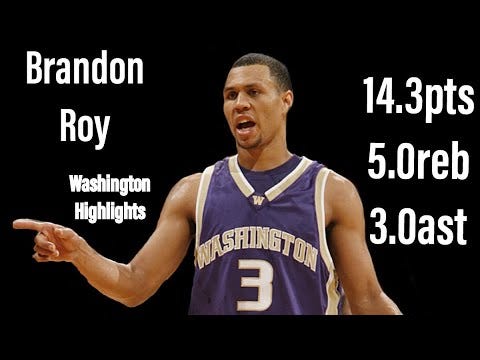

In terms of great moments for the on-court product, the 2005 Washington vs. Arizona game was excellent: Two teams vying for a No. 1 seed with elite-level talent; longtime NBA players like Channing Frye and Nate Robinson, one of the greatest shooters ever in Salim Stoudamire, and a huge What If NBA’er in Brandon Roy.

Stoudamire erupted for 37 points in what was among his very best individual games at UA, but Washington’s second-half rally propelled the Huskies to the title and the West Region’s top seed.

As for that Arizona team, it went the rest of that March without any notable second-half implosions!

Appropriate transition here, as Washington basketball hit its peak in the mid-2000s. The resurgence of Arizona and UCLA certainly benefits the Pac-12, as those are the standard-bearers. But the league was always at its best in the ‘90s and ‘00s with either Stanford or Washington at comparable levels.

Stanford recapturing that magic it had under Mike Montgomery is a tall order, but there really isn’t much reason for Washington not to be a year-in, year-out contender to Arizona and UCLA. Seattle is quietly one of the better prep basketball cities in America, and UW being an outstanding academic school gives it a pitch to recruits outside of the local pipeline. An inability to lock down Seattle has hurt Washington historically; I think back to the ‘90s and the vital role Michael Dickerson and Jason Terry played on great Arizona teams.

As far as basketball goes, I view Washington like Illinois where both have had high peaks in my time following the sport, but endure quizzical lulls given the bevy of local talent.

In football, Washington compares to Michigan. Both have rich history, which is a blessing and curse. The curse stems from the expectations set from that history without taking into consideration the overall changes to the landscape.

Academically, Michigan and Washington are more comparable to schools like Cal or Northwestern than they are Ohio State or Alabama. In Michigan’s case, having to compete directly with Ohio State makes placating fans who want a return to the old days especially difficult.

Washington doesn’t have an Ohio State in its conference. USC has the potential, but it’s merely that. Winning a national championship might be pie-in-the-sky for UW, but the landscape is such that the Huskies should routinely win 10-plus games and play for Pac-12 titles regularly.

It’s been too long since NJPW featured outsiders in its annual G1 Climax — 2016, in fact, when Pro Wrestling NOAH sent Naomichi Marufuji and Katsuhiko Nakajima, both of whom acquitted themselves quite well. Marufuji actually opened that tournament with a win over IWGP Heavyweight champion Kazuchika Okada, setting up a title match at that year’s King of Pro Wrestling event.

The G1 becoming as homogenous as it’s been actually runs counter to the tournament’s original concept of showcasing talent from a variety of promotions. To wit, Steve Austin and Rick Rude wrestled in the second edition with Rude reaching the final against Masahiro Chono.

About a decade later, Jun Akiyama reached the final at a point when NOAH was red-hot and NJPW was slipping into the doldrums of Inokiism2. The resulting finale between Akiyama and Hiroyoshi Tenzan ranks among my favorite G1 matches ever, and helped elevate Tenzan’s profile as a main-event talent.

With all that said, I understand NJPW curtailing outsider involvement. The promotion had ample talent within its own ranks — prior to the pandemic restrictions that forced some questionable inclusions, anyway — to stage an excellent tournament. Since it’s ultimate a New Japan product, adding outsiders through the Forbidden Door means expanding the G1 beyond its current 20 to avoid cutting out NJPW wrestlers.

But to do that without taking a greater physical toll on the participants — the G1 is grueling enough as it is with nine matches — the format would need to change. My proposition is a 40-man G1 with four different blocks of 10, mixing 20 outsiders with 20 NJPW wrestlers, and the winner of each block advancing to sudden-death semifinals.

Before unveiling the list, I’ll address my lack of WWE inclusions. Even in a fantasy scenario, I cannot envision it working particularly well. I would love to see Chad Gable or Roman Reigns wrestle stars like Okada, Hiroshi Tanahshi or Minoru Suzuki, but the style that WWE emphasizes gives me some hesitance.

All Japan: Kento Miyahara

AEW: Miro, Eddie Kingston, Bryan Danielson, Pac, Jon Moxley, Hangman Adam Page, Kenny Omega

NOAH: Go Shiozaki, Takashi Sugiura, Kenoh, Katsuhiko Nakajima, Kaito Kiyomiya, Naomichi Marufuji

DDT: Konosuke Takeshita, Tetsuya Endo, Yuki Ueno

Impact: Josh Alexander

Freelancers: Masato Tanaka, Daisuke Sekimoto

NJPW: Kazuchika Okada, Tetsuya Naito, Hiroshi Tanahashi, Zack Sabre Jr., Minoru Suzuki, Tomohiro Ishii, Hirooki Goto, YOSHI-HASHI, Taichi, Jeff Cobb, Will Ospreay, Kota Ibushi, SANADA, EVIL, KENTA, Toru Yano, Jay White, Shingo Takagi, Great O’Khan, Hiromu Takahashi3

Divide however you see fit, but I would want to see a final four of Okada, Naito, Daniel Bryan and Shiozaki culminating in an American Dragon vs. Tetsuya Naito finale.

Led by the Elam Ending account on Twitter itself, which comes off smug and combative. It’s made me less of a fan of the concept, I won’t lie!

Some day, sooner than later, I plan to dive deep into the history of Inokiism, which is as much a sports story as it is wrestling.

I’m using this format to springboard Takahashi from the Junior Heavyweight division, where after three Best of the Super Juniors wins and a handful of long IWGP Junior Heavyweight title reigns, he’s reached his ceiling.