Team sports’ most dominant dynasty effectively ended 50 years ago this week. David Thompson was the man who brought it down.

OK, so that woefully undersells the contributions of Monte Towe, NC State’s savvy point guard who controlled the flow of the game for the Wolfpack on their way to the 1974 national championship.

Likewise, 7-foot-2 center Tom Burleson’s presence in the paint opposite UCLA’s Bill Walton — one of the two greatest players in college basketball history — played a critical role in NC State’s 80-77 defeat of UCLA in the national semifinals.

Walton went for 28 points on 13-of-21 shooting and grabbed 18 rebounds, so he wasn’t exactly held in check.

But considering Walton had 44 points on 21-of-22 shooting in the National Championship Game a season earlier and was shooting almost 67 percent from the floor in the 1973-74 season, Burleson’s effort was the most solid any big man delivered against the UCLA legend on the big stage.

And, for his part, Burleson posted a 20-point, 14-rebound double-double in the overtime win.

David Thompson’s double-double of 28 points and 10 rebounds, however, stole the show. It’s not the reason, but at least one reason that Thompson’s No. 44 is forever immortalized in NC State basketball lore, retired and hanging from the rafters.

“David is 6-4 and he plays much taller,” John Wooden said following the game. “He’s the best 6-4 man I’ve seen.”

Now, the legendary Wooden’s comments were wrapped in a backhanded compliment, comparing Thompson and Walton. Wooden touted his own player, as a coach should, invoking the conventional wisdom of the time.

“Walton is 6-11 and he jumps out of the gym…If center is the position you want, I don’t think you have a choice. Thompson may jump like a center, but he doesn’t have the body. Walton does. I consider them both great, but I don’t think NC State where they are if Thompson were their center.”

True, having the 7-foot-2 Burleson to complement him helped Thompson — just as Walton worked well in concert with the versatile Jamaal Wilkes.

Still, basketball was a constructed from the outside-in at this time. Wooden’s protege Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was the best player in the NBA, following in the mammoth footsteps of Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain before him.

Walton moved onto the pros and took the NBA by storm with the Portland Trail Blazers. He joined a league shaped in the image of Kareem, Bob Lanier, Wes Unseld, and after Walton, Moses Malone.

Kareem’s Fourth Wall-breaking moment in Airplane!, which I will post to The Press Break any chance I get, provides a glimpse into the NBA of the time.

Of course, college basketball was no different. Kareem and Walton were the two best players the college game had ever seen, and they came up in a stretch when Elvin Hayes, Lanier and Artis Gilmore elevated Houston, St. Bonaventure and Jacksonville to Final Fours.

The 6-foot-4 David Thompson leading NC State to the 1974 national championship marked a transformational period for the game, however.

Thompson claimed the Naismith Award the next season after Walton monopolized the National Player of the Year honor for three straight seasons. A center did not claim it again until Ralph Sampson kicked off his own three-year stretch dominating the Naismith in 1981.

Perhaps more significant, a team built around a dominant center did not win the national championship for a decade when Patrick Ewing and Georgetown outdueled Hakeem Olajuwon and Houston in 1984.

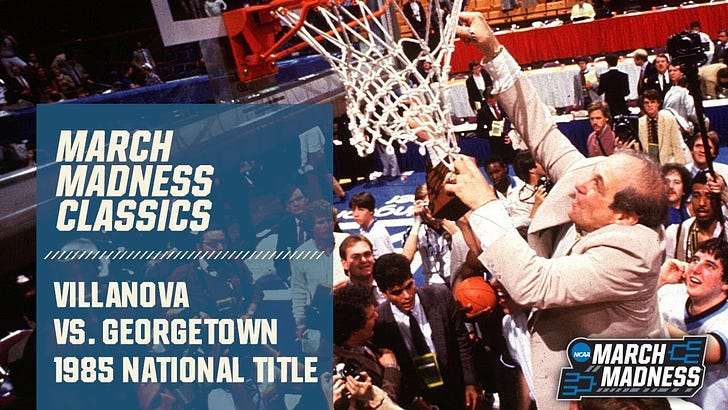

Now, both Georgetown with Ewing and Houston with Hakeem came within seconds of national titles prior to 1984 — Hakeem’s UH Cougars against an underdog NC State team, at that. Ewing again fell just moments shy in 1985 when Villanova played a near-perfect National Championship Game.

Final Four Fact February: When The BIG EAST Ruled The World

March 1985 is a little before my time, but I imagine a day spent as a teenager then going a little something like this: You walk out of your local two-screen cinema from a showing of Friday the 13th: A New Beginning with a satin Starter jacket on and your pant legs tucked into your fresh, new Nike Terminators. You step into your parents’ Buick and turn …

NC State’s David Thompson-led national championship and his subsequent National Player of the Year recognition hardly ended the age of big-man basketball. But Thompson arguably helped usher in a renaissance for a game in which building a championship team around an athletic wing could be a viable strategy.

***

Growing up, the suggestion Julius Erving provided the blueprint for Michael Jordan wasn’t uncommon. Dr. J’s free-throw line take-off dunk to win the 1976 American Basketball Association dunk contest, contrasted with Jordan’s own foul-line dunk from the ‘88 NBA dunk contest provided one of the more memorable parallels.

Early-to-mid 1970s basketball has long fascinated me, and I credit the comparison between Doc and MJ for contributing to that. My dad recounting seeing Dr. J and George Gervin play in the ABA when he lived in San Antonio further sparked my interest.

Flipping through some of my dad’s books on that timeframe educated me on an underappreciated time in basketball.

Most notable are Terry Pluto’s chronicle of the ABA, Loose Balls; Foul!, which digs into the blackballing of Connie Hawkins amid point-shaving allegations during his abbreviated time at the University of Iowa in the early 1960s; and Rick Telander’s dispatch from New York, Heaven Is A Playground.

I read Heaven Is A Playground in its entirety the summer between my sixth-and-seventh-grade years, and the book made quite an impression on me. For those unfamiliar, it’s a master work of sports journalism wherein Telander spent a summer in the neighborhood that produced legendary James “Fly” Williams, himself a March Madness star during his time at Austin Peay.

Mid-Major Monday: Fly Williams and the Tragedy of a Basketball Trail Blazer

Because the streets is a short stop Either you slingin’ crack rock or you got a wicked jump shot In the summer of 1995, my love of two artforms were taking shape: sports journalism, and hip-hop music. Works from each medium that I consider seminal captured my 12-year-old imagination: Rick Telander’s book

Williams’ tragic story is one that feels too common among transcendent basketball talents of the ‘70s, which is why the era seems to loom in the sport’s background.

College basketball’s ‘70s history does not, for my money, receive enough attention for how influential it was. The decade produced perhaps the greatest collection of true college legends of any period in the game’s history, culminating in but hardly limited to Bird and Magic.

Gilmore and Lanier; Walton, Sidney Wicks and Marques Johnson at UCLA; Scottie May and Kent Benson leading Indiana’s perfect 1976; Adrian Dantley; Phil Ford.

And, of course, David Thompson. Were it not for Walton, Thompson might be the star of ‘70s. And, for that one NCAA Tournament, Thompson was THAT GUY.

My theory about ‘70s college basketball’s greatness being something of an afterthought is that the postseason hadn’t gained its current prominent in the zeitgeist until the ‘80s.

Present-day NBA voices and pop culture seem to paint the ‘70s as the Dark Ages, meanwhile. It’s a perception not entirely without merit: the ABA’s meek flame-out despite having top-tier talent that was on-par with the NBA’s, the NBA struggling to grow its TV audience, and high-profile drug issues bog down how the decade’s remembered.

David Thompson’s career is front-and-center at each of these crossroads.

He debuted professionally in the ABA, joining the Denver Nuggets in the league’s final season. Never really mentioned in Erving’s 1976 dunk contest clip, which lived on through virtually every NBA Home Videos release I owned in my childhood, is that the rookie Thompson debuted some revolutionary stuff in that same event.

Thompson’s lone ABA season produced Rookie of the Year honors, and he finished second in MVP voting behind Doc.

Indicative of the assertion that the ABA’s top players were just as good as the NBA’s, the next season, Thompson was seventh in NBA MVP voting; Erving was fifth.

By 1978, Thompson finished third in MVP balloting behind the winner Walton and fellow ABA alum, George Gervin.

That was as high as Thompson ever ascended in the MVP race, however, as both his on-court production and his off-court life unraveled due to drug abuse.

In an interview before the 1983 season, Thompson described himself as a “splurge user” of cocaine and that he welcomed testing as part of any contract he received.

Four years later, however, a Washington Post headline reads:

“Jail The Latest Stop In Downward Spiral Of David Thompson”

The lede laments that Thompson’s NBA career appeared over at age 32 — and the prediction was correct. Thompson lasted played in March 1984, 10 years after occupying the college basketball mountaintop.

Thompson’s life hit bottom as Michael Jordan’s career was on a meteoric ascent. In this context, it makes sense that Jordan drew favorable comparisons to Dr. J.

Just as Thompson reached a fast downslope, Erving’s career crescendoed with a Most Valuable Player selection in 1981 and a champion with the 76ers in 1983. Of course comparing Jordan, the budding face of the game, to the successful, breakout star of the previous generation made more sense than paralleling him to an addict who flamed out just when he should have been hitting his apex.

But watching highlights of a young Thompson, one could contend there was more of DT’s game evident in Jordan’s than elements of Erving’s.

Erving was listed at 6-foot-7 in his career, just an inch taller than Jordan, but photos of Doc banging with the 6-foot-9 Magic Johnson suggest Erving was on the tall side of 6-foot-7. If nothing else, Erving’s long arms and deceptively broad upper torso are much more forward than guard.

What’s more, both Thompson and Jordan were North Carolina kids — DT from Shelby in the west, MJ from Wilmington on the Atlantic coast — and each led in-state universities to national championships.

Jordan co-signed the comparisons years later, choosing Thompson to induct Jordan into the Basketball Hall of Fame.

Some of the stigma associated with ‘70s basketball seems to be softening thanks to moments like this.

Last year traveling to, from and around Houston for Final Four weekend, I read Theresa Runstedtler’s book “Black Ball” and it took me back to some of the reads on the sport I enjoyed as a kid.

After years of narratives shaped mostly by Bill Simmons’ influence decrying the pre-Magic and Bird NBA as a wasteland of dope, violence and bad basketball, I appreciated a more nuanced examination.

And it’s with nuance that, as NC State makes a run to the Sweet 16 in 2024, we can look back at the Wolfpack’s national title run of a half-century ago with appreciation for what David Thompson was. He didn’t singlehandedly change the sport, but he played a prominent role in a larger revolution that helped mold today’s game.

More importantly, Thompson conquered his demons. His story is one from basketball’s mislabeled era with an ending worthy celebrating, even if every chapter was not so triumphant.