Mid-Major Monday: Fly Williams and the Tragedy of a Basketball Trail Blazer

Because the streets is a short stop

Either you slingin’ crack rock or you got a wicked jump shot

In the summer of 1995, my love of two artforms were taking shape: sports journalism, and hip-hop music. Works from each medium that I consider seminal captured my 12-year-old imagination: Rick Telander’s book Heaven is a Playground, a journal of a summer spent on the New York playgrounds in the 1970s; and Notorious B.I.G. debut album “Ready to Die.”

Now, whether I should have been listening to Biggie as a 12-year-old is debatable — and to my parents’ credit, they didn’t let me so much as I bought it at a local Hastings and the teenage clerk either didn’t recognize or didn’t care about the PARENTAL ADVISORY sticker on the CD case.

Heaven is a Playground, on the other hand, was a gift from my dad. He recognized my budding interest in reading sports journalism, which quickly progressed from SI for Kids, to proper Sports Illustrated and SLAM.

SLAM, then in its early days, covered basketball with depth and style that was unmatched. For a basketball-obsessed youth living in a rural and ethnically/culturally homogenous, SLAM functioned as a gateway to worlds I’d otherwise have no exposure.

Coinciding with my burgeoning love for hip hop, which started with Snoop Dogg, Naughty by Nature, Method Man and Biggie, I went through a crash course on different experiences and perspectives. As the son of public school teachers in a state notorious for underfunding education (Arizona), I sometimes thought my family was poor; music and basketball taught me I knew nothing of poverty and hardships.

The above lyrics, from Biggie’s “Things Done Changed,” expresses a dire reality for some deeply and generationally impoverished kids in New York’s projects: The only way out of this situation is to sell drugs or defy all odds and earn opportunities with basketball.

James “Fly” Williams did both. Tragically, drugs won out.

Wallace’s upbringing was a byproduct of the Reagan-era crack epidemic that ravaged Black communities, hitting New York especially hard. Williams predated the crack plague, instead transitioning from college basketball star with a promising pro future to cocaine abuser and dealer.

Telander’s Heaven is a Playground, which I dad gave me after seeing me devour SLAM features on NYC playground legend Earl Manigault and the Dunbar Poets, and watch the three-hour-long documentary Hoop Dreams more than once when I was in sixth grade, is set in 1973 in Fly Williams’ neighborhood.

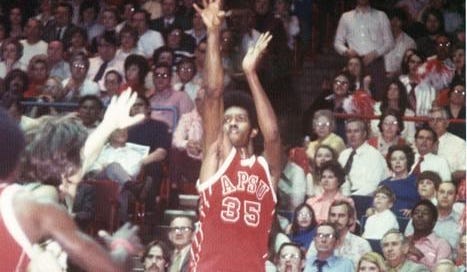

This was just months after Fly led Austin Peay to the NCAA Tournament, averaging almost 30 points per game in the 1972-73 campaign and scoring 74 points in postseason matchups with Jacksonville, Kentucky and Marquette.

He knocked down a game-winner against JU, and took Kentucky to overtime in a 106-100 loss, bringing the New York playground flair that earned him his nickname to the traditional, and in some ways still very homogenous world of college basketball. Remember, we’re talking just seven years after the Texas Western national championship.

Now, perhaps reading that a product of New York projects led Austin Peay, a school in Clarksville, Tennessee, gave you whiplash. As a kid reading Heaven is a Playground, I initially thought little of it until the book spelled out some of the culture shock Fly experienced.

For one thing, Fly came to Austin Peay in 1972, just five years after the SEC had its first Black player in Vanderbilt’s Perry Wallace. Austin Peay had only welcomed its first Black team member two years prior, L.M. Ellis.

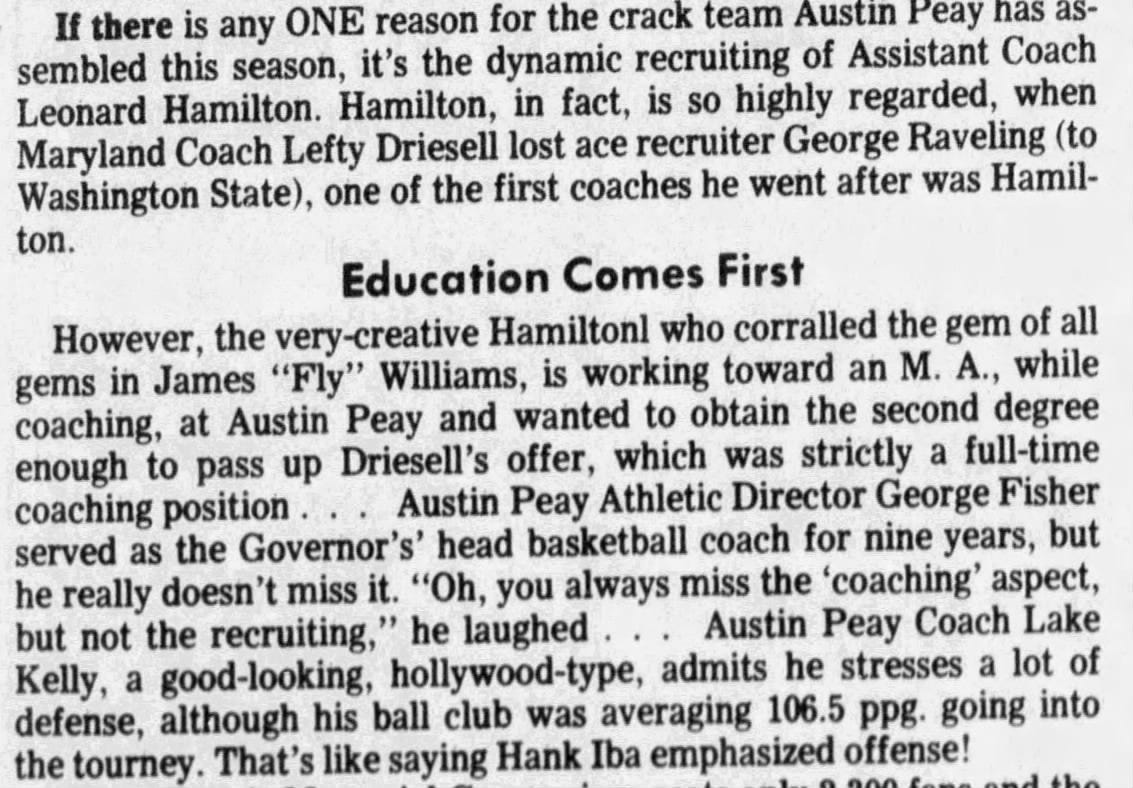

But Austin Peay employed a Black assistant coach in the ‘70s, someone of whom you may have heard — current Florida State head coach Leonard Hamilton.

The lore around Fly’s recruitment says Hamilton slept in his car on the dangerous streets of New York for days at a time in his efforts to woo Williams. That level of persistent explains Florida State’s success under Hamilton, as well as adding some context to this passage from a December 1972 Inquirer & Messenger (Owensboro, Kentucky) feature on the Governors basketball team:

The summer after which Heaven is a Playground is set, Williams returned to Austin Peay and again pushed the Governors to the NCAA Tournament. The chant of “FLY IS OPEN, LET’S GO PEAY!” is my favorite college basketball cheer of all-time.

With his high-scoring brand of basketball, comparable to revolutionary players of the day like George Gervin and Julius Erving. Doc’s name comes up frequently in association with Fly, having come up on the same New York courts and transitioning to become a scoring machine in college.

Also like Doc, Fly jumped from college early to join the ABA. But while Julius Erving began to build a legacy that endures today, Williams spent one unremarkable season with the Spirits of St. Louis alongside another tragic basketball figure, Marvin Barnes.

A retrospective on Fly’s fall published last year at Sports Illustrated recounts a Williams story in which he refers to himself as “the drug guy.” Sadly, it’s a prescient commentary on how Fly will mostly be remembered; his exploits on the New York playground and in leading Austin Peay to NCAA Tournaments a tragic footnote in his series of arrests that includes his 2017 bust for running a heroin ring.

In much the same way that I still consider Notorious B.I.G. one of my greatest ever musicians, despite releasing just one album during his lifetime and a second recorded for release just before his 1997 murder, I view Fly Williams as one of the most fascinating figures in basketball history.

I don’t sympathize with Fly; heroin and other opioids have become the same kind of scourge today that the crack epidemic was for a young Christopher Wallace’s neighborhood in the 1980s. In studying the stories that set the backdrop of lives like Biggie’s and Fly’s, I can at least understand how the New York product with the jump shot wicked enough to escape backslid in the end.