Inokiism, Jake Paul, MMA and Wrestling

It’s no secret to those who know me that I love professional wrestling, and have for a very long time. That said, I made a vow when launching this newsletter I would relegate any pro-wrestling content to Patreon, lest I lose the audience who subscribe for sports commentary. Sometimes, however, the two worlds converge — like the WWE signing college football players to NIL deals and the prevalence of former football athletes in professional wrestling.

If there’s nothing else I learned in three decades following the Sport of Kings, it’s how to effectively plug my work. Thanks, Mick Foley!

To that end, it’s impossible to delve into the history of mixed martial-arts without getting into wrestling.

An assortment of anniversaries converged in recent weeks for fans of combat sports. June 23 marked 20 years since one of the most famous bouts in MMA history, a bloody slugfest between legendary fighter Don Frye and Yoshihiro Takayama.

PRIDE FC featured the match, and for those unfamiliar with the Japanese promotion…well, its backstory is worthy a column all its own.

PRIDE offered a lucrative landing spot for early UFC fighters like Frye, Kevin Randleman and Mark Coleman at a time when John McCain-led congressional pressure dissuaded state athletic commissions from hosting the fledgling Ultimate Fighting Championship. PRIDE served as the launching pad to stardom for the key figures in UFC’s late 2000s rise like Quentin “Rampage” Jackson and Chuck Liddell.

The promotion also associated with the Yakuza, a partnership that accelerated PRIDE’s demise.

Before then, however, it gained a fair bit of attention stateside thanks to a best-of series on FOX Sports Net in the first half of the 2000s. After classes in these days, I would often turn on my TV, which was on FSN from watching college basketball the night before, and found myself sucked into PRIDE.

That’s when I first saw Frye-Takayama, and I’m as astounded with this bout now as I was then.

The match is all the more impressive given that Frye is a UFC Hall of Famer, and Takayama is a professional wrestler.

Now, longtime readers of mine probably don’t need to be informed that I am a longtime wrestling fan. I no longer watch WWE and haven’t for several years, instead primarily following New Japan Pro Wrestling.

However, an American of my generation or younger isn’t into wrestling without having WWE as any entry point. And, as most boys of my generation were, I was a rabid “Stone Cold” Steve Austin fan in the late 1990s.

Thanks to Austin on World Wrestling Federation programming and the New World Order on World Championship Wrestling, wrestling gained a level of mainstream popularity at this time that it had not before reached, and never since come anywhere close to replicating.

That popularity will never return, either. Entertainment options are too splintered and niche, and late ‘90s wrestling struck a chord that worked in the cultural framework. Reality TV as we know it today was in its infancy, the prison-bound conmen behind Enzyte and Girls Gone Wild aggressively pushed their products on basic cable advertisements, and sleaze sold.

No one was more willing to satiate an audience hungry for sleaziness more than a sleaze in his own right, Vince McMahon.

For as much as envelope-pushing content drew in the audience, however, I always preferred wrestling shows for the wrestling matches. At the turn of the millennium, this was a bit akin to claiming to enjoy Playboy for the in-depth journalism it featured rather than the pictorials — which was also the case for me in college! — but it was the truth.

It’s one reason that around 1998, I preferred WCW Nitro to WWF Raw because of the former’s showcasing of revolutionary talents like Eddie Guerrero, Rey Misterio Jr. and Ultimo Dragon, as well as solid ring technicians like Diamond Dallas Page. And, it’s why I remained loyal to wrestling by around 2001 when my classmates lost interest, as WWF had curtailed some of the Jerry Springer influence and delivered on all-time classic matches.

Still, friends with whom in 1998 I went to the local video stores to rent VHS of past WWF, WCW and the rarely available ECW pay-per-views shifted by 2000 to UFC.

Coincidentally, this was during the federation’s “dark ages,” as they’re popularly referred. I lived in Arizona, and my home state’s senator fought to ban UFC from promoting shows in the United States or airing on pay-per-view.

McCain’s “human cockfighting” declaration achieved two things, one of them unintentional: It prompted athletic commissions to bar UFC from obtaining licenses, forcing the promotion to run shows in places like Dothan, Alabama. And, it gave MMA just the right air of taboo to appeal to turn-of-the-millennium edgelord teens.

Thus, my buddies and I would rent UFC tapes. I remained steadfast in my wrestling fandom, even as peers scoffed at its fakeness contrasted with the legitimacy of MMA, but I also became a UFC fan.

One show I remember renting and watching with classmates especially vividly was UFC 19: Young Guns, which featured a collective favorite of our watch party, Kevin Randleman. It also included a grudge match between Tito Ortiz and a member of Ken Shamrock’s Lion’s Den, Guy Mezger.

Being a wrestling fan, and knowing Shamrock as an early pillar of MMA, I immediately disliked Ortiz for arrogantly flipping off the legend during the show. I felt a level of vindication years later when Ortiz served an embarrassing, abbreviated term as mayor of Huntington Beach, California.

UFC 19 ran in March 1999, two months after a pivotal clash of MMA and wrestling.

* * *

In a medium as attractive to abnormal people as professional wrestling, Antonio Inoki stands out for being particularly noteworthy.

Inoki served as a politician in Japan during the 1990s and, an ill-conceived effort to impress voters, worked with the North Korean government to stage a wrestling show/unity festival in Pyongyang.

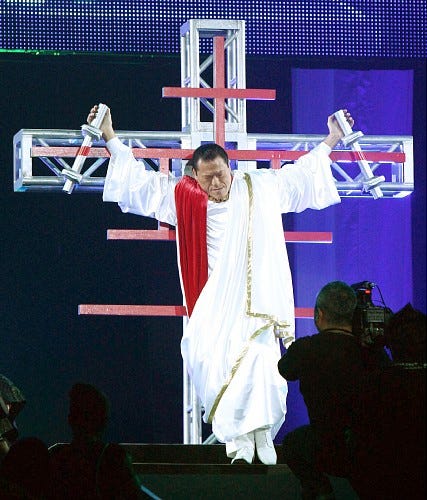

Inoki has staged various MMA shows, including one in which he was carried down the entrance ramp on a cross in a baffling display of sacrilege.

Before politics and blasphemy, Inoki gained fame as a wrestling megastar. He trained under the legendary Rikidozan, and in 1972, founded New Japan Pro Wrestling.

NJPW’s 50th anniversary is this year, while this week marks the anniversary of Inoki’s most famous foray into the United States. On June 26, 1976, Inoki took on Muhammad Ali in an exhibition at the Nippon Budokan.

Floyd Mayweather vs. Big Show1, this wasn’t. Inoki had legitimate training in grappling and striking, and fought Ali in an unscripted bout. Had there been a script, the end result wouldn’t have been as painfully dull as the match turned out — nor as devastating to Ali’s health in his final years as a boxer.

Inoki remaining close to the mat and delivering a series of leg kicks that kept Ali at a distant and prevented the fight from ever engaging in an exciting fashion sent The Greatest to the hospital. And while initial reports called his injuries “superficial,” this Los Angeles Times article from the bout’s 40th anniversary reveals Ali nearly had to have his leg amputated.

Although Ali vs. Inoki was nearly two full decades before the first UFC show, the former foreshadowed the latter in two significant ways: The idea of proving which fighting discipline is the “best” is an attraction, but the end result is often painfully dull.

The earliest UFC cards are brutal — and not in the human cockfighting manner that McCain depicted. Yes, there’s objectionable content, the byproduct of having very few formal rules and no weight classes. But really, Royce Gracie’s original idea proved better in concept than execution.

Dana White’s credited with saving UFC as a promotion and MMA as a sport, but much of the praise with regard to restructuring the federation’s rules borders on myth-making. Weight classes had been implemented by the time I started watching UFC tapes, two years before White became the company’s president in 2001. The assorted barred strikes that early UFC touted to sell PPVs were banned by late 1997.

White and the Zuffa group deserve credit for their successful re-branding and marketing of UFC, which gave MMA legitimacy it previously lacked in the mainstream. But as far as the actual product, it was well on its way in the evolution to being a more genuine sport.

Antonio Inoki recognized MMA’s rising popularity. In Japan, mixed martial-arts lacked the political/social stigma it carried in the United States during the 1990s — hence American stars like Don Frye surfacing there, and UFC even staging a show in Yokohama — and threatened to overtake pro wrestling in mainstream viewership.

Sensing the shift, Inoki sought to blur the lines between MMA and wrestling at the turn of the millennium; a concept referred to as Inokiism.

Jan. 4, 1999, is the unofficial birth of Inokiism. In the Tokyo Dome for New Japan’s annual supershow, popular main-event wrestler Shinya Hashimoto faced former Olympic silver medalist and world champion judo athlete Naoya Ogawa. Ogawa wrestled for a smaller, invading promotion that itself was already leaning into the blurred lines between legitimately attacked Hashimoto to Hashimoto’s surprise, signaling the beginning of an era when wrestlers under Inoki’s employ were expected to prove themselves in shoot fights.

Yuji Nagata — a fast-rising star of NJPW at the time — was put into matches with top-level MMA fighters Mirko Cro Cop and Fedor Emelianenko. Nagata was a college wrestler and thus had some genuine combat-sports chops, but had no business being placed opposite two of the best in the sport at the time.

Nagata’s loss to Cro Cop on New Year’s Eve 2001 only serves to underscore how monumental a feat Takayama hanging with Don Frye truly was.

And while a foray into MMA bolstered the reputations of pro wrestlers Katsuyori Shibata, Shinsuke Nakamura and the aforementioned Takayama, Inoki’s insistence on drawing attention between the athletic competition of MMA and scripted nature of wrestling damaged the latter to the point of nearly decimating New Japan Pro Wrestling.

For those who watched wrestling at its apex in the late 1990s, imagine the poorly received and immediately abandoned Brawl For All concept, wherein WWF wrestlers were placed in legitimate boxing matches against one another. However, instead of boxing each other, they faced Evander Holyfield — and the wrestlers chosen for that spot included “Stone Cold” Steve Austin.

That’s exactly how asinine placing Nagata in an MMA with Fedor proved to be.

Similarly, Inoki’s commitment at this time to promoting “legitimate” fighters — among them PRIDE and K1 star Kazuyuki Fujita, former Washington Huskies lineman2 and K1 kickboxer Bob Sapp, and sumo champion Tadao Yasuda3 — did nothing to woo MMA fans.

Former NCAA national championship-winning wrestler Brock Lesnar’s tenure as IWGP Champion didn’t just fail to win over new or former fans; Lesnar dealt perhaps the most devastating blow to the company’s credibility of the Inokiism era, taking the company’s top belt home in 2006 and refusing to relinquish it after a handful of lackluster matches.

But the harm Lesnar did to pro wrestling in Japan flipped upside with his elevation of MMA in the United States not long after.

* * *

I noted in the intro that one cannot dig into the history of the MMA without mentioning pro wrestling. Really, the same can almost be said of combat sports as a whole.

The aforementioned Ali set the standard for drawing big box-office returns with an interview style that made him a legend. Ali’s bombastic presentation established a benchmark in boxing that being just the best pugilist wasn’t enough; not if you were going to command the most notoriety and thus largest paydays.

His precedent is why the endlessly fascinating Mike Tyson remains a cultural icon today, and recognition of Lennox Lewis — a better fighter by an assortment of metrics and the kind of straight-laced athlete so many often claim they want to represent their sports — is limited to boxing hardcores.

The same is true of wrestling, where being able to command the audience’s attention on the microphone is as important — and in some cases, more important than — doing so in the ring. While Ali’s flamboyant aura predates the rise of wrestling’s most noteworthy talkers like Ric Flair and Dusty Rhodes, who took inspiration from The Greatest, MMA is a more clear example of combat sports borrowing from the squared circle.

UFC in particular replicates the American professional wrestling format for hyping a bout almost to a tee: Combatants give interviews expressing their disdain for each other, the more hyperbolic the better.

I don’t necessarily believe it’s the best formula for a legitimate sport to mirror, since the promoters have no control over who wins and loses. A byproduct of that is UFC has had a tendency to promote charismatic fighters ahead of better athletes. Chael Sonnen remained a main-event figure well after his performance warranted thanks largely to his 1980s wrestling-inspired interviews, and Conor McGregor’s continued prominence despite a dreadful half-decade.

A problem with relying too heavily on marketing is it leaves a fighter’s reputation open to some devastating blows when a more effective showman gets on the microphone.

Nevertheless, I can understand UFC going to the wrestling well. After all, pro wrestling arguably helped pull MMA in the United States out of the depths and elevated its stature another decade later.

Of those anniversaries I mentioned, another a few months later this year is the 20th of a pivotal card in UFC history. The rivalry that bubbled for years between Tito Ortiz and Ken Shamrock reached its boiling point in November 2002 at UFC 40.

The Ortiz-Shamrock bout marked the first time I remember ever seeing mainstream outlets covering UFC. A highly wrestling-influenced interview with Ortiz and Shamrock aired on FOX Sports, and video hype packages leading up to the fight were comparable to those WWE produced for its pay-per-views.

I was in college by this time, and UFC 40 was the first time I can recall my new friends showing interest in the sport. Like countless other turn-of-the-millennium teen boys, they were lapsed fans of pro wrestling during the height of WWF’s Attitude Era and their ears perked up at the mention of former Intercontinental Champion Ken Shamrock fighting in the Octagon.

There’s a bit of chicken-and-egg with Shamrock and whether MMA or wrestling was the more element. Shamrock gained mainstream exposure in his nearly three years with WWF, during the company’s peak of drawing power. But he also gained his spot in wrestling through his legitimate tough-guy reputation cultivated in early UFC.

Either way, the two converged to give Shamrock an appeal others in a UFC still trying to shake its bad rap lacked. The results are inarguably, with UFC 40 drawing more than 100,000 in pay-per-views, almost equal the combined sales of the two cards preceding and immediately following it.

That Shamrock and Ortiz had legitimate beef certainly helped the authenticity of the build, while the fight itself going down as an instant classic helped establish UFC as a viable sport long-term.

UFC 40 also cemented my dislike of Ortiz, who grew into a de facto top heel of the sport, or a bad guy who you’ll pay money in hopes of seeing lose using wrestling parlance. I wasn’t alone, either: Ortiz’s well-promoted UFC 47 bout with Chuck Liddell in April 2004 was the company’s first PPV to garner 100,000-plus buys since UFC 40.

Anecdotally, it was also the first time that I saw a stranger out in public repping UFC. I had a chat about the fight the day after with the fella working at the counter at a gym my girlfriend (now wife) dragged me to for a spin class, to which I agreed despite drinking Harry Caray-levels of Budweiser the night before. A poor choice, but I digress.

Liddell-Ortiz became a major linchpin in the sport’s mid-2000s growth, airing repeatedly on FSN in the same vein as Frye-Takayama to help build excitement for a rematch. When they met again two-and-a-half years later, it became the sport’s most-watched show to that point and marked the first time UFC pushed 1 million PPV buys.

With Shamrock vs. Ortiz laying the foundation, MMA gained a foothold in mainstream American sports. But American combat sports have a tendency to only go so far as the heavyweight division takes it. Here’s where Brock Lesnar re-enters the frame.

* * *

Brock Lesnar debuted on WWE TV in 2002, just two years after winning the NCAA wrestling championship for the Minnesota Golden Gophers.

Lesnar moving onto pro wrestling at that time stands to reason: Former Oklahoma State amateur grappler Gerald Brisco headed up WWF’s scouting, and 1996 Olympic Gold medalist Kurt Angle was on a meteoric rise in the company.

For him to debut in April 2002 and win the top championship by August is remarkable, as his exit from wrestling less than two years later. Lesnar’s wrestling arc, which turned 20 this spring, parallels his UFC run.

Lesnar debuted in UFC less than two years after his disappearance from New Japan, and just seven months after returning NJPW its IWGP Championship belt (via an intermediary of Kurt Angle. Lesnar faced Angle at an Inoki-promoted mixed MMA and wrestling show in the summer of 2007).

Despite losing his February 2008 UFC debut, Lesnar made an impact arguably more profound than in his wrestling debut. The former NCAA champion wrestler worked his way into a heavyweight title shot the same year and began a three-year run as arguably the most hated man in the sport — ironically, or maybe because of the very reason he was such a draw.

Lesnar’s pro wrestling background drew eyeballs that may not have otherwise checked out the UFC during one of its most pivotal moments of growth. He headlined the promotion’s first million-buy PPV when challenging MMA legend Randy Couture for the championship, then replicated the feat in 2009 in a rematch with Frank Mir, who handed Lesnar his UFC debut loss.

Lesnar attracted 1 million-plus PPV buys again in 2010 facing Shane Carwin, and a third time later that year against Cain Velasquez. The sport hadn’t had a more reliably bankable draw before, and didn’t again until the latter-half of the 2010s with McGregor.

Each of these milestones come together to consummate the athletic world’s most unique marriage of sport with performing art.

In 2008, boxing champion Floyd Mayweather Jr. appeared at WrestleMania XXVIII in a match against former Wichita State basketball player Paul “Big Show” Wight.

Sapp started on the 1994 Washington team that ended Miami’s unbeaten streak at the Orange Bowl, a game nicknamed “The Whammy in Miami.” For a thorough dive into the consequences of that matchup, check out the deep-dive I did for Patreon subscribers.

Sumo wrestling’s own legitimacy came into question not long after Yasuda’s disastrous IWGP Heavyweight Championship reign, as a 2011 investigation found extensive match-fixing in the sport. That may well be a topic for a future edition of this newsletter…