At the beginning of the 2022-23 college basketball season, four programs1 that qualified for NCAA Tournament participant since the event’s inception in 1939 never made the field. By March, that unfortunately exclusive club was whittled down to three, but not because one of the four finally broke through.

St. Francis Brooklyn dropped all athletics, a decision formally announced on March 20 — one day after the Terriers’ Northeast Conference counterpart Fairleigh Dickinson, fresh off beating No. 1 seed Purdue, gave eventual Final Four participant Florida Atlantic a handful in the NCAA Tournament’s Round of 32.

St. Francis Brooklyn dropped all three of its matchups with Fairleigh Dickinson in the ‘22-’23 campaign, including the first step in the Knights’ March Madness journey — an 83-75 final in the NEC Tournament — and the last game in Terriers history.

FDU is little more than a background character in the long history and untimely demise of Saint Francis Brooklyn basketball, but the New Jersey school offers a frame of reference into the tragedy of the Terriers folding.

Mike Vaccaro chronicled in the New York Post SFBK coach Glenn Braica beginning preparations for 2023-24 after a promising end to 2022-23. Braica was in the process of collecting commitments from his roster to return, a new wrinkle to the difficulties of college basketball at lower levels in the present day due to the transfer portal, and the team seemed energized by Fairleigh Dickinson’s recent success.

“A lot of them,” Braica told the Post, “saw what FDU did and said to themselves: ‘That could be us next year.’ And I mean I just couldn’t wait to get back at it.”

FDU advancing in the NCAA Tournament, especially just a year removed from winning only four games (Saint Francis Brooklyn won 14 this season), would understandably prompt its peers to ask, Why not us?

The answer to that question, sadly, is money.

St. Francis Brooklyn’s NEC rival Knights slayed a proverbial dragon, both in terms of the monstrous mismatch Zach Edey and Purdue presented on paper, and in the vast wealth of the Purdue athletic department compared to that of most other Div. I members.

The Big Ten Conference signed a broadcasting right contract that goes into effect this July worth $7 billion. Most universities’ entire athletic budget is worth a fraction of the revenue Purdue and its Big Ten counterparts take in.

David-and-Goliath dynamics in March Madness take on a whole new meaning when evaluating early-round matchups by the measure of money, a point underscored effectively in this Sportico feature on Fairleigh Dickinson’s creative athletic budgeting.

Rather than David vs. Goliath, maybe these Tournament games are more comparable to Bilbo Baggins and Thorin Oakshield’s Company taking on Smaug who, like the Div. I power conferences, just keep hording more and more revenue.

A common refrain in the arguments for NCAA reforms states that there’s never been more money flowing through college sports than ever before — and that’s true. But it’s confounding that with the billions coming in either through the joint CBS/WBD venture to broadcast March Madness, or the individual contracts ESPN and FOX have brokered (and to a much lesser extent, CBS), entire departments can die off.

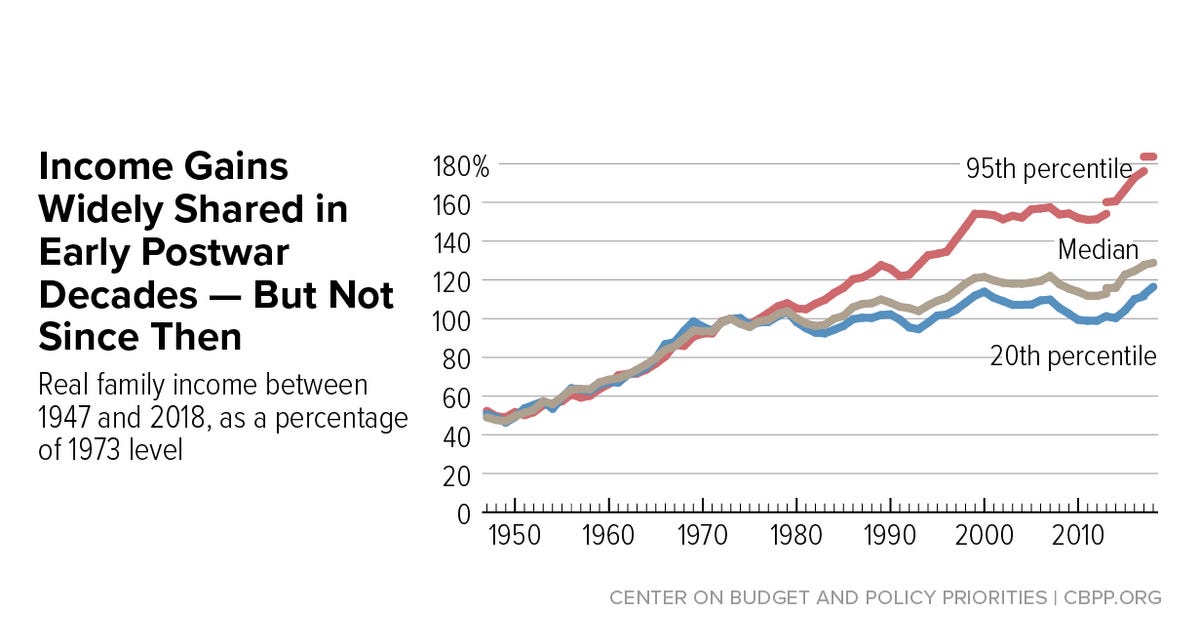

1984 marked the most pivotal point in TV money’s influence on college sports, which if nothing else is a fitting coincidence given the parallels to the nation’s overall wealth gap exploding consistently since the ‘80s.

Saint Francis Brooklyn’s closure was, of course, a budgetary decision. The college’s official announcement specifically cites challenges as a result of COVID, another noteworthy coincidence given the pandemic provided the impetus for a flood of changes to college sports — chief among them, the implementation of the transfer portal and allowing athletes to profit off of likeness.

I am, and have for some time been, a proponent of college athletes earning wages off of endorsements. This 2018 deep dive illustrates some of my thoughts. I am vehemently opposed to college athletes being designated as university employees for a variety of reasons, among them the financial implications for schools in the current landscape struggling just to stay afloat.

Perhaps it’s conspiratorial on my part, but I fear the post-COVID momentum of reforms functioning as a Trojan horse for the Smaugs of college sports — those athletic departments already awash in cash — to horde even more while cutting out the St. Francis Brooklyns and Fairleigh Dickinsons of the world.

Do we reach a point when leagues like the Big Ten opt to circumvent the embarrassment of losing to an NEC program by freezing them out of March Madness altogether? The Big Ten did, after all, briefly adopt a scheduling bylaw that would have barred its members from scheduling non-conference football games against FCS programs2 — FCS programs that receive a substantial portion of their annual athletic budgets from playing such games.

That bylaw was fortunately walked back, but that it was at one point on the table concerns me. It’s especially concerning in the current climate.

As for St. Francis Brooklyn specifically, its closure is heartbreaking. The program has a rich history far exceeding its status as an answer to the trivia question, who’s never made the Tournament.

SFC was a founding member of the Metropolitan New York Conference, a league that was instrumental to the sport’s growth in the ‘30s and ‘40s. It shared conference membership with a national champion, CCNY, a Final Four participant in NYU, and rivaled St. John’s during its growth into a program of national prominence.

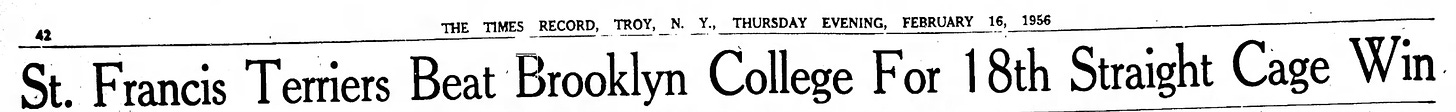

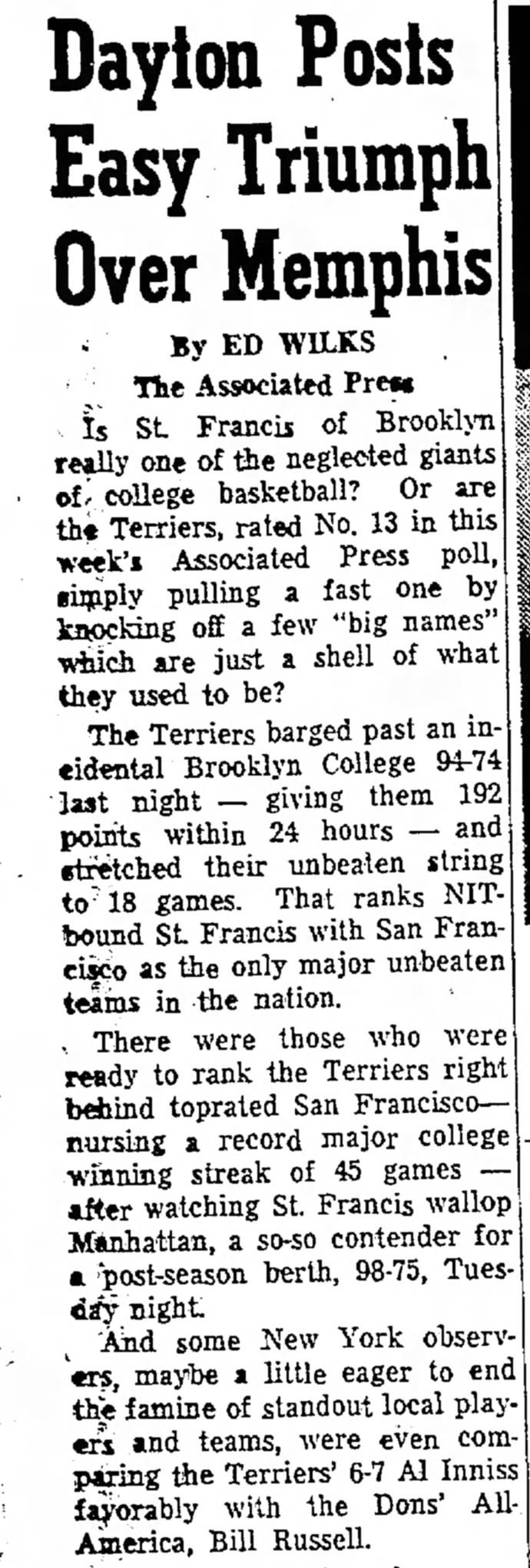

The ‘55-’56 Terriers reached No. 13 in the national polls, and even at a point, had national columnists asking if St. Francis College might contend with San Francisco and Bill Russell for the national championship.

College basketball is worse off any time it loses a program, but particularly a program with the history of St. Francis Brooklyn — even if that history lacked a March Madness moment.

Army West Point, The Citadel, St. Francis Brooklyn and William & Mary.

Another coincidence: In much the same way Purdue came out on the losing end of arguably the most staggering upset in March Madness history, Big Ten member Michigan lost the most infamous power conference vs. FCS game in history.