Ways in which the 1994 strike changed the landscape of Major League Baseball have been dissected ad nauseum over the last 30 years, including the tangible, financial implications of the work stoppage.

But, in case you didn’t realize it, this ain’t Sportico, pal. The Press Break specializes more in the intangbile, and the MLB strike certainly produced a variety of intangible changes.

Most commonly referenced is MLB’s decline in popularity. Anyone at all familiar with the sport’s place in the zeitgeist before 1994 can tell you, without having to reference Nielsen ratings or anything of the sort, that baseball was undeniably more prominent before the strike.

However, there are spikes post-strike that suggest Americans still viewed baseball as their Pastime: The 1998 home-run chase and the 2001 World Series captivated the country in unique ways that no other sport could match, the clearly overall more popular NFL included.

Whether the strike was a hinge event unto itself, or merely one contributing factor in a series of factors working against baseball’s prominence consistently for the last 30 years, each argument has validity.

Similarly, the 1994 strike’s impact on the death of the Montreal Expos and resurrection as the Washington Nationals may be one in a variety of factors. The strike may have had no impact at all on an inevitability.

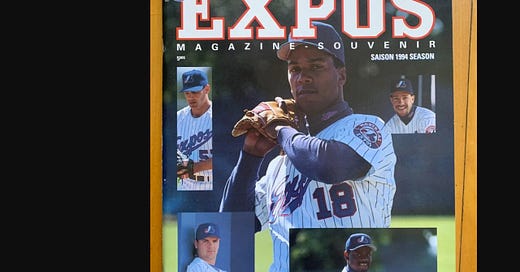

But on the return of The Press Break’s What-If Wednesday, I ask you to revisit summer 1994 in the weeks leading up to the work stoppage and ask what would have happened to the Montreal Expos had a settlement been reached and the season continued?

Allow me to preface this entry with a personal aside: The Expos fascinated me from my earliest days seeing baseball, typically when my dad had on Cubs WGN telecasts.

Both played in the National League East, and like all NL East teams, the Expos had certain players whose names ring through my memory in Harry Caray’s cadence when they came to at-bat.

To be clear, the often inebriated jovial Harry adopted a low, grim manner of speaking when it came to reputed Cubs Killers. For the Pittsburgh Pirates, it was Andy Van Slyke, Barry Bonds and Bobby Bonilla — and in the case of Bonilla, he joined Howard Johnson among New York Mets who prompted that audible grimace from Caray.

A few of these batters played for the Montreal Expos in the first half of the 1990s. In 2024, I could log onto Baseball-Reference or another such spot and pull up the exact numbers; perhaps even invalidity my own memories.

But this edition of What-If Wednesday is asking you to get into the 1994 mindframe, which means if I want to use the internet — excuse me, The Information Superhighway — to contextualize my perspective, I can only do so with a 28.8K modem and hope the AOL disc that came in the mail buys me sufficient time to surf.

Thus, I’ll give you my memories of the Cubs and Expos clashing: Delino DeShields would be enshrined in Cooperstown if he only played the Northsiders, and the trio of Larry Walker, Marquis Grissom and Moises Alou combined to form the greatest outfield in baseball history.

Oh, and if you’re lucky enough to steal a game at Olympic Stadium, consider it a win: It’s impossible to take a full series from that French-Canadian Terrordome.

Given this was my impression of the Expos in the childhood underscores a few things: The Cubs were pretty bad in the first half of the ‘90s, and my early years closely following Major League Baseball overlapped with an extremely rare window of success for a mostly downtrodden franchise.

Despite Chicago’s futility against Montreal, I didn’t harbor the same ill will toward the Expos I did toward the Mets. In a way, I liked the Expos for the little I saw of them.

DeShields was a terror on the base paths, Walker bashed dingers, and Alou ended up being a favorite Cub of mine in the 2000s.

And then there was Olympic Stadium.

Olympic Stadium wasn’t the only domed ballpark in the National League, but I viewed the Astrodome as a football stadium nice enough to welcome the Astros in during the offseason.

Olympic Stadium, however, was the Expos home. And it appealed to me in a way difficult to describe but similar to my feelings about Idaho football’s Kibbie Dome. It’s not some ironic and lame Sickos navel-gazing, yucking it up to get a load of this shitty place!, but rather a genuine fascination of and appreciation for its uniqueness.

What’s more, Montreal seemed exotic to my childhood brain. Yes, it’s a naive view of a city that’s only a five-hour drive from Boston, and perhaps clouded by Quebec’s French-speaking population. Nevertheless, of all the cities with Major League franchises then, Montreal seemed the most far-flung of them all.

And, as I got older, I came to appreciate the Expos as underdogs. I especially loved the 2002 team. Reminiscing on Vladimir Guerrero, Orlando Cabrera, Jose Vidro, Brad Wilkerson and Bartolo Colon takes me back to my freshman year of college and playing as the Expos on the Playstation 2 title High Heat Major League Baseball.

Talk of the Expos leaving Montreal exploded around that time after MLB took over ownership from Jeffrey Loria. I hoped a hot finish to the 2002 season might carry over into 2003 and build a groundswell of support for a new owner to emerge. While the late-season success of 2002 did carry somewhat in to 2003, ownership committed to Montreal never materialized.

2002 and 2003 marked the first time since ‘93-’94 Montreal produced back-to-back above-.500 records. It wasn’t enough to get the Expos into the Playoffs, however, effectively ending the organization’s run in fitting futility.

Before the late ‘90s, however, I didn’t realize until years later that the Expos played in exactly one playoff series. That one series was played before I was born — and, coincidentally, in the last work-stoppage shortended season, 1981.

Montreal’s stretch of five seasons ending with above-.500 records from 1990 through 1996 was the most sustained success the franchise enjoyed since producing a .531 or better winning percentage four straight years from 1979 through 1982.

And yet, not once from ‘90 through ‘96 did the Expos make the Playoffs. Blame the old postseason format, in which the winners of the two divisions that made up each league were the only qualifiers, for denying the 87-75 Expos of 1992 and the 94-68 Expos of 1993 spots.

The restructuring of Major League Baseball ahead of the 1994 season, which expanded each league by a division and awarded a Wild Card playoff berth would not have saved the Expos’ playoff prospects. The outstanding Atlanta Braves teams of the early ‘90s moving out of the West would have relegated the Pirates and Phillies squads that bested Montreal in the East into the Wild Card.

However, in 1994, the Wild Card offered an ace-in-the-hole that presumably would have landed the Expos in the postseason regardless how the cancelled month-and-a-half remaining on the schedule unfolded at the time of the strike.

Not that Montreal needed the Wild Card in 1994.

One-hundred and fourteen games into the 1994 season, at the outset of the strike, the Expos held a six-game lead over Atlanta in the NL East and won two of the three head-to-head series played to that point.

The second Montreal series win over the Braves included a 5-3 defeat in which Greg Maddux made the start for Atlanta, the Expos’ second straight victory in a game that the dominant Maddux took the hill.

The Expos won a 7-2 game in June, part of a series that demonstrated how much of a baseball city Montreal could have been with a consistent, winning product on the field.

The late-June series even predated a pivotal stretch in which Montreal ripped off 20 wins in 23 games. The Expos were red-hot and showing no signs of slowing down when the strike began on Aug. 12.

Jack Todd’s column in The (Montreal) Gazette a week earlier characterizes the beginning of the strike as “like falling madly in love — with someone who’s moving to Mongolia next month.”

When things rekindled post-strike, none of the ‘94 Expos ended up in Mongolia — but many may as well have been.

Larry Walker won Most Valuable Player in 1997, his third season with the Colorado Rockies.

Marquis Grissom won the third of four straight Gold Gloves in 1995 as a member of the Atlanta Braves. He was on the opposite side of Ken Hill, who’d had a breakout 1994 season with the Expos, in the 1995 World Series; Hill was pitching for Cleveland.

Moises Alou and Cliff Floyd each got their chances to play in the World Series two years later, winning rings with the Florida Marlins.

The young, rising star of the Montreal pitching staff in 1994, Pedro Martinez, stayed around longer than most of the core of the ‘94 Expos. He won the Cy Young Award in 1997, becoming the only Cy Young Award winner in franchise history.

Pedro won two more in 1999 and 2000 with the Boston Red Sox.

Would simply qualifying for the Playoffs in 1994 have saved baseball in Montreal? Probably not. Despite the success of the previous seasons, then-owner Claude Brochu was unable to put the money together to maintain the powerhouse roster built prior to the strike after the league returned in 1995.

Winning a World Series, on the other hand, may well have done the trick.

Beyond the obvious impact winning a championship has in cultivating a fan base, the attention may well have sparked the investment into the club that Brochu could not secure and that was necessary to retaining some star talent.

How much of a fan base a World Series run could have built beyond Canada — or even just the Quebec province — is questionable.

But one year removed from the Canadiens winning what is still today the last Stanley Cup won by a Canadian NHL franchise, an Expos World Series may well have galvinized Montreal around an identity as a city for champions. Think Boston at its peak when the Patriots, Celtics, Red Sox and Bruins all won titles in less than a decade.

Getting that taste for winning, transforming 25 years of built-up apathy into an expectation for success, may well have been the key Montreal was denied.

Organizations that move in pro sports almost always do so amid stretches of consistent failure. No franchise in any of the four highest-profile leagues has moved within a decade of winning a championship since the Hawks left St. Louis for Atlanta in 1968, exactly 10 years after the only NBA title in club history.

The St. Louis Rams left for Los Angeles 17 years after winning a Super Bowl, though that was a unique situation given the organization originated in LA. The closest a team has come to moving within a decade of winning a title was the Minnesota North Stars relocating to Dallas just thre years after reaching the Stanley Cup Finals.

Winning organizations do not typically move. A more common occurrence in the last 30 years are transient franchises finding immediate success upon moving, however: The Baltimore Ravens winning a Super Bowl five years removed from sustained misery as the Cleveland Browns; the aforementioned Dallas Stars hoisting the Stanley Cup six years removed from being the North Stars.

And, in 1996, the Colorado Avalanche won Lord Stanley’s Cup in their first season after moving from Quebec City.

The Nordiques had struggled mightily in the latter half of the ‘80s into the ‘90s, qualifying for the NHL Playoffs just once from 1987 through 1994.

In the lockout-shortened 1994-95 campaign, however, Quebec City finished with the best record in the Eastern Conference. A playoff flameout against the defending Stanley Cup champion New York Rangers ended the Nordiques’ existence, but the pieces that were in place that season — Joe Sakic, Peter Forsberg, Patrick Roy — were primed to win a Cup.

And they did so. In Colorado.

Now, it’s important to note Montreal and Quebec City are two vastly different cities with their own identities and a very real rivalry. I’m not going all national NFL reporter erroneously suggesting San Diego and Los Angeles fan bases are one in the same.

I bring up the Nordiques and their immediate Stanley Cup win as the Avalanche not because it affected the people in Montreal, those who followed hockey surely loving the Canadiens.

Rather, the Nordiques may have offered a warning about letting a championship-caliber franchise slip away to the States.

The Expos simply never proved to be championship caliber, which is what the 1994 season’s cancelation took from them.