What If Wednesday: Charlie Ward in the NFL

There are a handful of college football moments I remember before the 1993 season: Desmond Howard’s Heisman-pose touchdown in 1991, Steve Emtman and the dominant Washington defense, Alabama beating Miami in the next year’s Sugar Bowl to seal the national championship.

‘93, however, was the season I credit for making me a college football junkie.

Living in Arizona at the peak of UA’s Desert Swarm defense certainly helped, and Tedy Bruschi wreaking havoc on opposing quarterbacks made an impression on me. But being a kid, I loved seeing touchdowns. My favorite player that season produced more than 30 of them — a lofty number for the era.

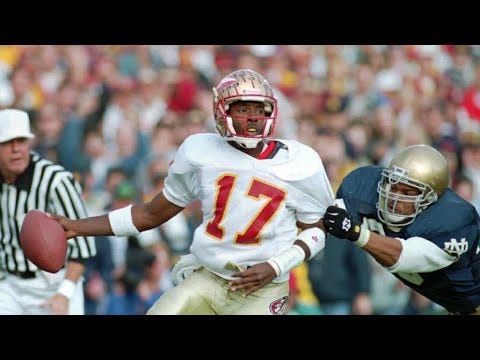

Indeed, Charlie Ward was ahead of his time. In some ways, he was too far ahead of his time.

“When they made the Heisman Trophy years ago and looked into the future,” then-Florida State running back Ken Alexander told Craig Barnes of the Sun Sentinel, “He was just what a Heisman winner was supposed to be.”

Ward’s style of play at Florida State did indeed establish a template for how the Heisman-winning quarterback of the 21st Century performs. Since Troy Smith in 2006, every Heisman winner save Sam Bradford in 2008 (11-of-12) rushed for more than 200 yards; each of those same 11 quarterbacks in at least one season, Heisman campaign or otherwise, ran for more than the 339 yards Ward totaled on the ground in 1993.

Juxtapose that with the quarterbacks of the ‘90s like Ty Detmer, Danny Wuerffel and Peyton Manning, whose rushing statistics total in the negatives, and it’s as if a DeLorean at 88 miles per hour dumped Ward off in Tallahassee for the expressed purpose of introducing the future of football.

NFL front offices were simply not ready, though.

Whereas all 11 of the aforementioned 21st Century Heisman winners were NFL draftees — many in the first round, and some like Baker Mayfield, Lamar Jackson and Kyler Murray all making an impact in the present day — Charlie Ward was deemed too much of a running quarterback for the pro game.

It’s laughable to look back on it now, particularly when arguably the best quarterback in the league, Patrick Mahomes, rushed more frequently in Texas Tech’s pass-heavy offense than Ward in Florida State’s shotgun-modified pro system.

The NFL not having a place for Ward hardly deterred his future. After teaming with Sam Cassell and Bob Sura to lead Florida State to the 1993 Elite Eight — which I discussed with Phil Cofer and Terance Mann amid the 2018 Seminoles’ return run deep into March Madness, and you can access at Patreon — Ward was a sought-after NBA commodity.

He spent a decade in the NBA, started for some excellent New York Knicks teams, flourishing on the hardwood with the opportunity denied him on the gridiron.

Really, it’s impossible to deem Ward’s path a failure. Hardly. Had some intrepid front office taken him in the 1994 NFL draft, it’s unlikely he would have been placed in a position to succeed.

Even in today’s era with dual-threat playmaking ubiquitous throughout college football, there’s still lingering stigma in the pros: Just look at 2014 Heisman winner Marcus Mariota’s struggles with a never-ending rotation of offensive coordinators at Tennessee, all of whom tried running basically anything but a system that accentuated his strengths.

This edition of What If Wednesday ponders as much about a coaching hire as the primary subject of Charlie Ward’s hypothetical NFL future. The league’s notoriously and historically slow to adapt, but every so often, innovators break through. Don Coryell and Bill Walsh deviated from the crowd in the ‘70s and ‘80s and became coaching legends.

Imagine a scenario in which an NFL franchise makes Chris Ault, who had just retired from Nevada (for the first time) in 1992, an impossible offer to turn down. Ault’s Pistol offense became something of a blueprint for pro teams adapting to dual-threat quarterbacks’ strengths nearly two decades after Ward’s Heisman season. Most notably, Jim Harbaugh and his San Francisco 49ers staff looked to Ault’s scheme when maximizing the ability of Colin Kaepernick during their Super Bowl XLVII run.

At Nevada in 2010, Kaepernick joined Tim Tebow (2007) and Cam Newton (2010, as well) as the only quarterbacks with at least 20 passing and 20 rushing touchdowns in the same season.

That both Tebow and Newton were first-round draft picks, and San Francisco picked up Kaepernick, speaks to the progress NFL front offices made since Ward. How much faster would it have been had a franchise drafted and given Ward the foundation to succeed?

A common cliche about the the NFL, which also explains its resistance to schematic changes, is that it’s “a copy-cat league.” Bill Belichick running an almost exclusively Shotgun-based offense in 2011 is a quintessential example, opening the door for franchises to explore more innovative and spread-influenced approaches.

College football was already steeped in such offenses by then, as the college game is often well ahead of the NFL on a variety of concepts. Walsh and Coryell starting as college head coaches is no coincidence. But had Ward come into a favorable situation in the NFL in 1994, before dual-threat playmaking was a stalwart of the college game, we could have seen the roles reversed with programs tailoring their offenses to recruit the next Charlie Ward.

While Ward played for an established national powerhouse, the majority of programs adopting similar concepts in reality were either lower level, or seeking a way to counter the heavyweights like Florida State.

To wit, Ault grew his scheme from Div. II and I-AA roots. Chip Kelly’s version of the hurry-up spread took shape at New Hampshire, and Northwestern’s use of a similar style against blue-bloods like Ohio State and Michigan inspired Mike Bellotti to change Oregon’s approach in direct response to USC owning the West.

Charlie Ward showing out in the NFL just might have flipped that relationship on its head, with the traditional powers building for dual-threat quarterbacks in the ‘90s and their counterparts having to adjust accordingly. Such a dynamic exists in the real world: Stanford under David Shaw, and with Derek Mason at defensive coordinator specifically, adopted a strategy meant to slow Oregon’s otherworldly offense.

Meanwhile, how much different would the NFL have looked embracing a more open brand of football nearly 30 years ago? Could teams quarterbacked by Trent Dilfer and Brad Johnson at the turn of the millennium been nearly as dominant?