The Legacy of the 2001 NBA Draft Class

NBA draft classes typically leave long-lasting legacies either as a result of being uncommonly loaded with talent (1984, 1996, 2003), or marked with dismal failure (2000).

The 2001 class produced a variety of quality NBA players like Zach Randolph, Shane Battier and Richard Jefferson; a couple who had remarkable peaks in Gilbert Arenas and Joe Johnson; and cornerstones of championship teams, Pau Gasol and Tony Parker.

No one from the 2001 class was transcendent, but it’s a strong group overall. On the 20th anniversary of the ‘01 draft, there’s reason to view it as one of the most transformative.

In 2001, the NBA was in its third year of a nine-season run in which every champion featured a Hall of Fame low-post player.

1999, 2003, 2005, 2007 - San Antonio, Tim Duncan

2000 to 2002 - Los Angeles Lakers, Shaquille O’Neal

2004 - Detroit Pistons, Ben Wallace

2006 - Miami Heat, Shaquille O’Neal

Thus, the first four picks in 2001 all being centers is just a reflection of the time no different than the Dwight Howard/Emeka Okafor draft a few years later.

The bevy of bigs taking at the top isn’t what makes 2001 so fascinating, and perhaps, the draft most reflective of a future two decades thereafter. It’s the group’s collective youth.

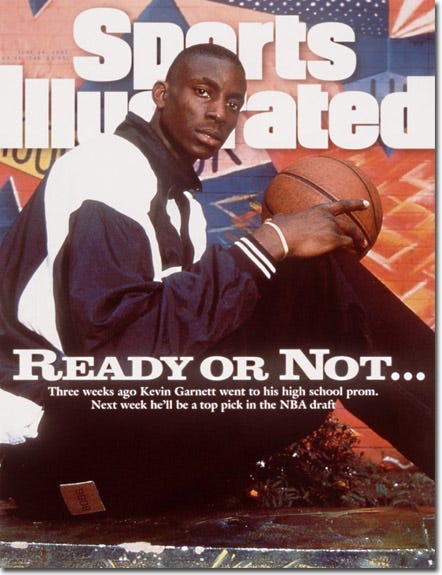

Just six years after Sports Illustrated imposed the headline “Ready or Not…” over a high-schooler named Kevin Garnett, three of the first four picks in the NBA draft jumped straight from the preps. Half of the first eight picks overall in 2001 were high schoolers.

Perception of prep prospects evolved quickly from 1995 to 2001. While the draft classes following Garnett included noteworthy high school-to-NBA busts — Korleone Young, Jonathan Bender, Leon Smith — KG, Kobe Bryant and Tracy McGrady were All-Stars by 2001. Jermaine O’Neal joined that group in 2002.

Paradigms shifted so dramatically, in fact, that SLAM floated the idea of DerMarr Johnson leaving after his junior year. By 2001, a rising junior in Ohio named LeBron James was touted in some circles as being a top 5 pick with two years of prep school still to go.

Credit — or blame — the shift in mentality for Kwame Brown, Tyson Chandler and Eddy Curry going 1, 2 and 4 in 2001, and DeSagana Diop going No. 8. High schoolers came with less mileage on their bodies, malleable in terms of developing to the NBA style, and with higher potential ceilings.

Sure, a prep prospect wouldn’t come in as a rookie and play at an All-NBA level, like Tim Duncan after four years at Wake Forest. But after rocky starts, Garnett, Kobe and McGrady picked up on the NBA style quickly; O’Neal was perhaps a worst-case scenario for a draftee who panned out, requiring five years to figure out. Once he did, however, he was one of the NBA’s best centers.

Indeed, there were tangible results and decent rationale to justify the investments placed in high schoolers. In retrospect, however, 2001 may have been the catalyst for the NBA implementing its still-in-tact age limit for draft prospects.

To be clear, deeming any of Brown, Chandler or Curry “busts” is a misuse of the label. Sure, none approached the levels expected of a top four pick; Chandler was the only one to have a real tangible impact on the NBA with his role in the Dallas Mavericks’ 2011 championship.

But all three appeared in 527 or more games spanning more than a decade. Even Diop, the most forgettable of the group, played in 601 games over 12 seasons. At its core, the operative word in professional basketball is professional; it’s a career. The 2001 draft’s quartet of lottery big men undeniably made careers from the NBA.

No. 1 overall pick Kwame Brown, whose name has become somewhat synonymous with busts, recently made a salient point about his staying power.

Brown’s social-media rants over the last few months have bordered on cringe, with some of the more thought-provoking insights obfuscated thanks to gas-bag charlatan Jason Whitlock attempting to leech onto Kwame.

Still, there’s value to be found in some of Brown’s points. Another, in addition to noting his longevity, was on the harsh realities Brown encountered upon joining the Washington Wizards.

Among the more startling revelations was of a teenaged Brown being physically threatened by Charles Oakley, friend of Brown’s legendary teammate Michael Jordan.

Just last year, the critically acclaimed docuseries The Last Dance took us into the proverbial sausage factory that was Chicago during Jordan’s illustrious career. Winning came at a steep price with Jordan, and Oakley threatening Brown certainly fits the M.O. detailed in Dance.

In no way does Jordan’s stardom nor his prior success excuse threatening a teenager less than half his or Oakley’s age — though it does speak to the challenges of going into the professional world at 18.

The 2001 class interests me on a personal level because I am the same age as those high-school draftees. The summer of 2001 coincided with my gap between ending high school and starting college. I never played against Tyson Chandler, but had been at the same camp as him once in 2000. While visiting California on a series of recruiting trips to D-II, D-III and NAIA schools, I watched a segment on one of the Los Angeles network news broadcasts about Chandler’s decision coming out of Dominguez High School.

During my senior year of high school, I followed the progress of Eddy Curry in the criminally forgotten docuseries Chicago Preps, which aired on the FOX Sports regional networks in spring 2001.

In a weird way, I felt a connection to the 2001 class I never had before and certainly not since. And viewing from the lens of my young maturation those subsequent years, I cannot fathom being thrown into a high-pressure, professional environment at that age.

I changed as a person considerably from the summer before freshman year until graduating a little more than four years later. Most anyone reading this, I suspect, grew emotionally, intellectually, perhaps even physically from 18 to 22.

From this perspective, I was at the time and remain a proponent of the NBA’s age limit. While there are exceptions, a workplace wherein millions of dollars for colleagues and billions for the employers are at stake is not a workplace conducive to success for a teenager.

And while basketball is a much different profession than whatever position any of us might have had the skills for at 18, any worthwhile workplace cultivates a young employees’ growth. The Brown dynamic in Washington is an extreme example, but nonetheless reflects how difficult getting on-the-job training can be in the NBA.

Someone like Jermaine O’Neal might have developed faster had he gone to South Carolina, been on the 1997 team that earned a No. 2 seed in the NCAA Tournament, and seen more than the roughly 11 combined minutes per game he averaged his first four years in the NBA. Ditto T-Mac, who could have been part of a national championship team at Kentucky when he languished on Toronto’s bench.

But whereas 2001 might have started the NBA in the direction of making adjustments, college basketball has reached the 20-year point and still hasn’t come to the conclusion it should have at the turn of the millennium.

While I firmly believe some time playing college basketball would have benefited each of Kwame, Curry, Chandler and Diop, no one should begrudge them their decisions. They earned life-changing money in those rough introductory years.

Hoop Dreams opened my sheltered eyes to some of the realities of growing up poor in Chicago, and Preps touched on many of the same themes with Curry. Tyson Chandler, while mulling over scholarship offers from Arizona and UCLA, was also enduring homelessness.

The flood of talent skipping college to go straight to the NBA — ready or not — should have been a wake-up call to the NCAA. Adopting the NIL policies set forth 20 years later could have been a small step; I have also long been an advocate of the NBA being able to draft college players and retaining their rights, paying a portion of their contracts while those athletes are still in the NCAA.

In hindsight, the 2001 draft could have been, should have been, the impetus for change to college basketball. Two decades of feet dragging now have politicians and the Supreme Court prepared to force action.