Shohei Ohtani & Fernandomania, Graig Nettles & Giancarlo Stanton, Dodgers vs. Yankees in the World Series

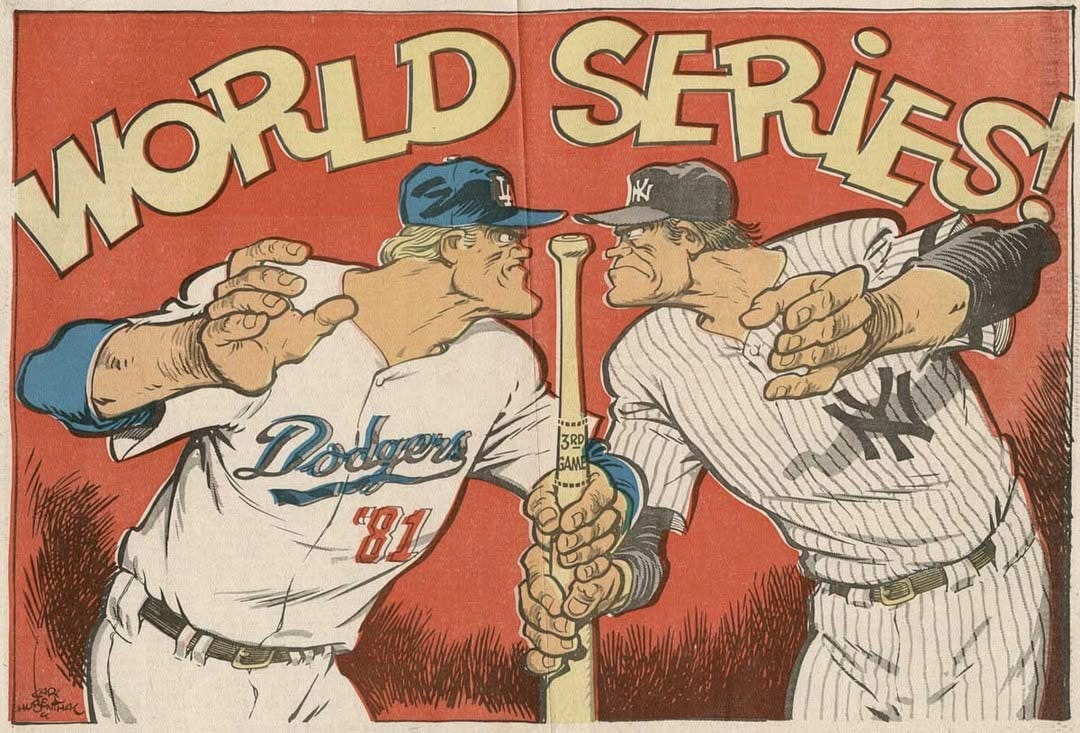

The 2024 World Series pitting the Los Angeles Dodgers against the New York Yankees shares similiarites with the 1981 edition of the Fall Classic.

A World Series pitting a Los Angeles Dodgers team featuring an international sensation against a New York Yankees side built around the batting of Hall of Fame-caliber home-run hitters—everything old is new again. Let’s talk about the 1981 World Series!

There’s no shortage of historical information to mine from a Dodgers-Yankees World Series matchup; the 2024 edition will be the 12th between the two.

The most recent, played in 1981, shares some similarities with the 2024 renewal of a once-backyard rivalry turned into a coast-to-coast peculiarity.

The 1981 MLB postseason sparked my curiosity years ago for a few reasons, primarily for first introducing the Wild Card to the sport. Of course, this wasn’t a true Wild Card in the sense we’ve come to know it since the mid-1990s.

Baseball’s first-ever Division Series were born of a strike-shortened regular season, much like the pandemic-impacted 2020 season that fostered the creation of the expanded Wild Card.

It took considerably longer to introduce the Wild Card and split the American and National Leagues into three divisions: 14 years, the expansion of two teams, and another strike. When MLB players went on strike again in 1994, it interrupted the best season in Montreal Expos history.

Coincidentally, the Expos’ only foray into playoff baseball came due to the expanded 1981 postseason. Montreal faced Los Angeles in one of the first two National League Division Series ever played, and the two went to a decisive fifth game at Olympic Stadium.

Dodgers ace Fernando Valenzuela took the mound for Game 5; certainly the starting pitcher Los Angeles would have most wanted in a do-or-die spot. However, Valenzuela took the loss in his previous start in the series—a 3-0 Game 2 Expos win—and Montreal struck with a first-inning run in Game 5.

That was the last run Valenzuela allowed. He went 8 2/3 innings, during which he surrendered only three hits. Reading about this series-closing game further impresses upon me just how good Fernando Valenzuela was, and why he earned such reverence that endures to this day.

I must admit to an embarrassing truth: My first exposure to just how culturally impactful Valenzuela’s peak was came not from a Sports Illustrated article or an episode of ESPN SportsCentury, but from VH1’s I Love the ‘80s.

For Gen Z readers of The Press Break, VH1 was a cable TV network that offered moms and dads a softer alternative to the teen-focused content of MTV…touches fingers to ear…And now I’m getting word that Gen Z has no familiarity with MTV’s significance to Gen X and Millennial youth culture.

OK, we’ll scrap the VH1 explainer then. Besides, it’s far more embarrassing to admit to those who remember VH1 that I first began to understand Fernandomania via the channel responsible for putting Ron Jeremy in a house with Verne Troyer, on the show where C-list comics offered pedantic quips on Bananarama and After M*A*S*H*.

Nevertheless, this sufficiently piqued my interest in Valenzuela enough that it inspired me to read more about his career and iconic status in Los Angeles sports lore. There’s far more informative material on him out there. I recommend this playlist on YouTube for a fascinating series of clips and features detailing Fernandomania’s significance both in real-time and with historical retrospectives.

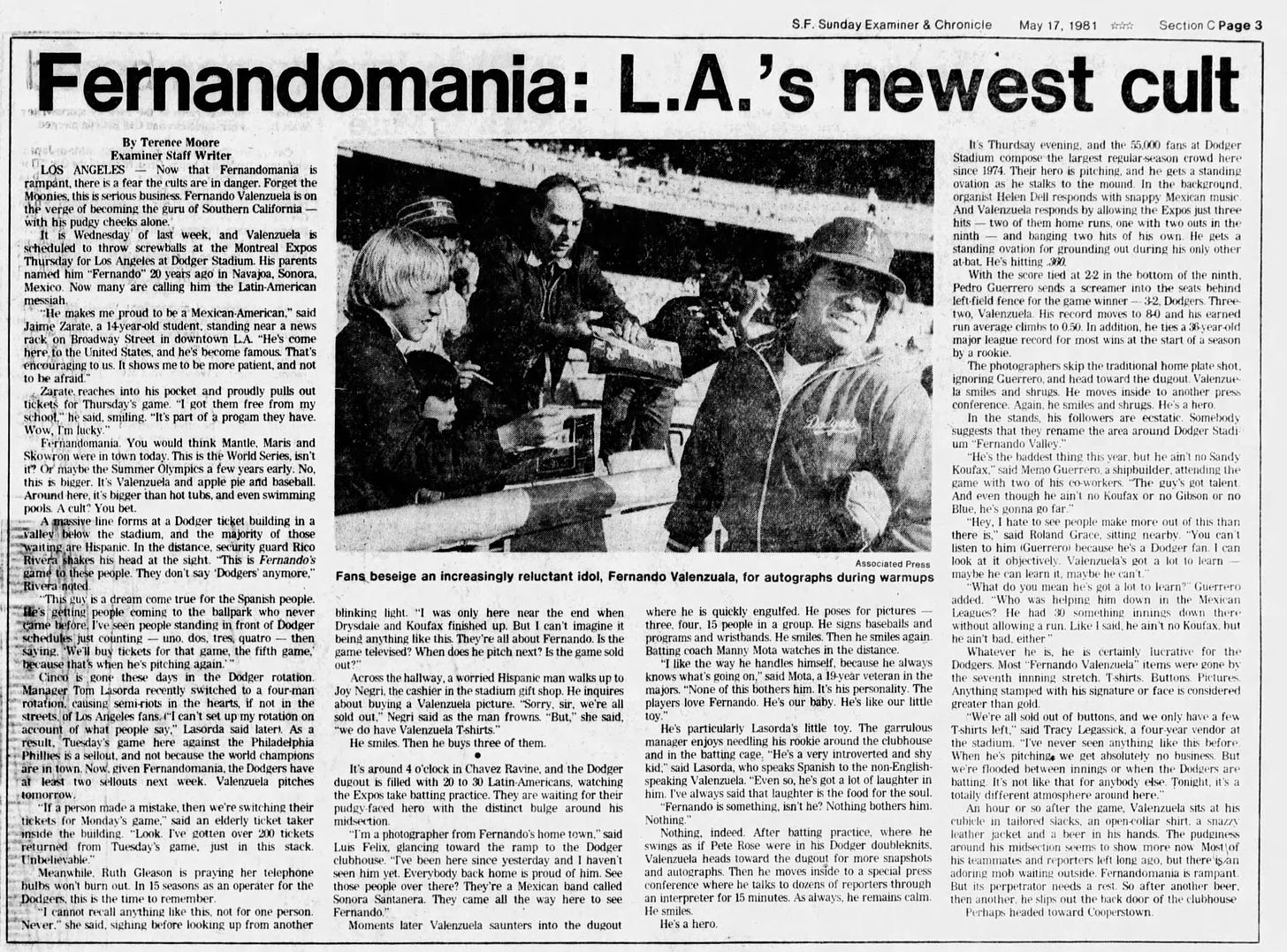

For those who, like me, were once uninitiated, a very brief synopsis: Valenzuela won the Cy Young Award in 1981 with a 2.48 ERA, pitching a remarkable 11 complete games in 25 starts with an unbelievable eight shutouts.

Half of Valenzuela’s shutouts came in his first five career starts. This opening stretch makes the remarkable first month Paul Skenes had this year look like child’s play — and it’s no wonder that Fernandomania grew around the Dodgers sensation.

Helping turbo-charge Valenzuela’s immediate rise to superstardom, which the San Francisco Examiner likened to a cult in the above article, he served as a cultural icon for the voluminous Mexican-American community of Los Angeles.

The fervor around Valenzuela reads like something of a precursor to the energy around Shohei Ohtani all season. Ohtani’s presence in the Postseason has been a boon to television ratings, and his impact is felt in his native Japan. Forbes’ Matt Craig had an interesting look at the astronomic TV numbers Ohtani’s producing on the other side of the Pacific.

Of course, Ohtani was no out-of-nowhere sensation upon joining the Dodgers like Valenzuela. Already arguably the best player in baseball a short drive south in Anaheim, Shohei signing with Los Angeles felt more akin to when the already talent-rich—and high-spending—Yankees of the 2000s signed Alex Rodriguez.

San Diego really needed a celebrity to channel Ben Affleck and go on a tirade to the media about the Ohtani signing. Alas, Tony Hawk is too chill for that.

Digression aside, Ohtani coming to the Dodgers finally placed what might be the best player in the game in a position to prove his excellence in October. I qualify with “might be,” as Yankees slugger Aaron Judge may have some say about that title.

It’s interesting how infrequently the World Series pits teams with two of the absolute best individual players at that given time against each other. This is pretty standard in the NBA throughout eras, speaking to the differences in how roster structure (and some luck) factors differently into baseball.

The 1981 World Series could arguably be one of the instances in which each team featured the best in the world at that time, with Valenzuela and Reggie Jackson.

Jackson was in his 15th season in 1981 but was coming off a campaign in which he won a Silver Slugger and finished second in American League Most Valuable Player voting. The next season with the California Angels, Jackson earned another Silver Slugger with his 39 home runs.

Jackson’s All-Star Game selection in 1981 was the 11th of 14 in his career. The 1981 World Series, meanwhile, was his final opportunity to add a sixth World Series championship to his resume after stealing the show in the famed “Bronx is Burning” 1977 Fall Classic and powering the Oakland A’s to a three-peat from 1972 through 1974.

For as many great teams as Reggie Jackson was part of in both Oakland and New York, I don’t think it’s out of bounds to suggest his most talented teammate ever was Dave Winfield.

Winfield is certainly among the most athletic players to reach Cooperstown: He was a versatile forward for the Minnesota Golden Gophers, good enough to be selected by the Atlanta Hawks in the NBA draft. Playing for Minnesota under the direction of coach Bill Musselman helped foster current USC head coach Eric Musselman’s passion for the San Diego Padres, which I chronicled for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

Winfield grew into a superstar for the Padres in short order, reaching his first of 12 consecutive All-Star Games in 1977. He ended his run in America’s Finest City with a second straight Gold Glove in 1980, one year after finishing a career-best third in MVP voting in 1979.

Winfield and Jackson shared an outfield for just one season. In the overall scope of their respective careers, however, they were two of the best players ever to play in the same Yankee outfield throughout the club’s illustrious history.

It’s a distinction that current Yankees Judge and Juan Soto share currently. Soto, who, like Winfield, came to New York from San Diego, was impressive this season: a .288 batting average, a .419 on-base percentage, 41 home runs, and very nearly one-dotting in OPS for the campaign.

And, like the Winfield-Jackson pairing, Judge and Soto could only be a one-year partnership. But that’s for after the World Series. In the meantime, Judge and Soto will try to win New York’s first World Series since 2009 and do something the 1981 Yankees couldn’t: beat L.A.

However, they’re not heading into the Fall Classic at the forefront of New York’s playoff push, based on American League Championship Series production. In that sense, 2024 is again comparable to 1981.

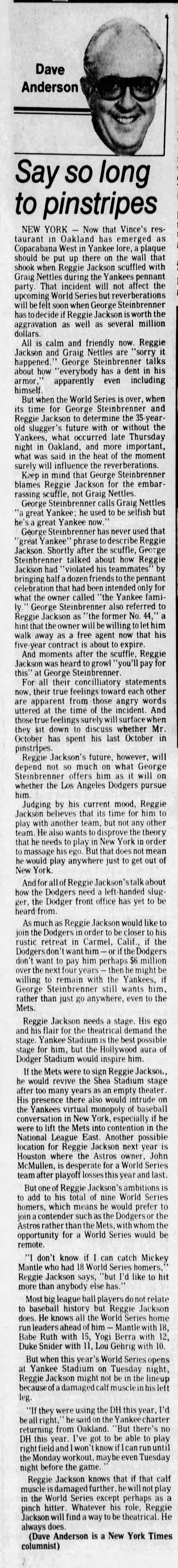

Among my favorite anecdotes tangentially related to the 1981 Yankees is that Artie Lange once revealed on The Howard Stern Show that he used Graig Nettles as a pseudonym when staying at hotels while touring the country for stand-up comedy shows. I appreciate the shout-out for a player whose contributions to Yankee lore fly under the radar for someone of a later generation such as myself.

That Nettles played on New York teams with future Hall of Famers Jackson and Winfield may contribute to the blind spot I have for Nettles’ career.

Nettles’ exclusion from Cooperstown might also be to blame. Upon further examination, Nettles might rank among the more controversial exclusions from the Hall of Fame, and certainly so among third basemen. He led the league in home runs in 1976 with 32, amid a stretch from 1975 through 1980 in which he made five All-Star Games.

His defense, which is much more difficult to quantify than batting statistics, could be the strongest argument for Nettles’ failed Hall of Fame candidacy. However, his play at third was critical to the Yankees winning the 1978 World Series—another Fall Classic pitting New York against its former Brooklyn neighbor now in Los Angeles.

The 1981 season marked the end of his career peak, with Nettles earning just one more All-Star Game selection after that point. It came in 1985 with his hometown Padres.

As for the defining stretch of his 20-season career spent in The Bronx, the last hurrah of '81 culminated in his winning Most Valuable Player of the American League Championship Series. Nettles drove in three runs in three games against the Oakland A’s, including a 4-for-4 performance in a 13-3 Game 2 rout.

It was a showing not unlike that of Giancarlo Stanton en route to the 2024 ALCS MVP. Stanton, who also once led the league in home runs with his 59 for the 2017 Miami Marlins, has been past his peak, whereas Nettles had not yet entered that downswing in '81.

But after a 2023 in which he hit .191 and drove in only 60 runs, the 2024 ALCS offered a return to classic Stanton form with his seven RBIs and home runs in 4-of-5 games.

Stanton will try to keep it rolling into the World Series, which Nettles did in 1981—until breaking his thumb.

Nettles went 2-for-4 and scored a run in Game 2, a 3-0 Yankees win that put New York ahead two games to none before heading to Los Angeles. Nettles again went 2-for-4 in the series’ return to Yankee Stadium, but did not play any of the three games at Dodger Stadium—all of which Los Angeles won.

The Dodgers, in fact, ripped off four straight to exact revenge for 1978, their run of victories ignited by—who else?—Fernando Valenzuela. His Game 3 win was actually one of his less dominant outings of 1981, with New York plating four against Valenzuela and four Yankees producing multiple-hit games.

Reggie Jackson wasn’t one of them, however: After being injured in the ALCS, he was sidelined for the first two games of the World Series and benched for Game 3 at what may have been the behest of George Steinbrenner.

An important part of the backdrop to the 1981 World Series was the contentious relationship between Yankees owner Steinbrenner and…well, everyone. But specifically in this series, Reggie Jackson.

For any drama that might loom in the present day as it pertains to Juan Soto’s contract or the relationship between Mookie Betts and Shohei Ohtani, it pales in comparison to the overwhelming presence of the late George Steinbrenner.

But maybe the 2024 World Series can get a dose of Steinbrenner from the Great Beyond; Dodgers fan Larry David voiced the barely fictionalized Steinbrenner on Seinfeld, after all.