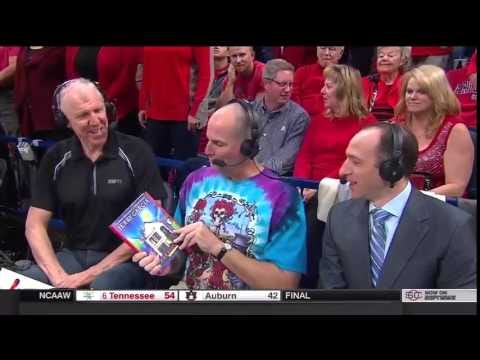

A generation of basketball fan best knows Bill Walton as ESPN’s irrepressible, tie-dye draped commentator; a comedic figure whose one-liners and soliloquies were advertised as prominently as whatever game he was calling.

However, to dismiss the Hall of Famer’s latter-career antics only as (possibly) THC-induced ramblings meant for entertainment is to miss on insightful nuggets. Bill Walton The TV Personality was not unlike comedian Mitch Hedberg in that regard.

Certainly some of Walton’s presentation on ESPN was played up for show, a point made clear whenever he partnered with Ted Robinson on Pac-12 Network telecasts.

The Bill Walton who worked alongside Robinson was much more grounded and analytic about a game — the game at which Walton excelled on a level few have ever reached. More on that in a moment.

But because Walton leaned into it more depending on platform doesn’t mean he was disingenuous, or that what he said more in-character wasn’t without merit. So many of Walton’s segments and rants on ESPN championed departments of universities represented in games he called, celebrated the ecological wonder of the regions, praised the artistic and cultural impacts made by the schools’ alumni.

Multiple friends texted me within minutes of my phone buzzing with the news alert about Bill Walton dying. All offered me a similar thought about the tragically fitting (or fittingly tragic) timing of Walton passing less than two full days after the final true Pac-12 sports event ever.

There is indeed a sad parallel that feels almost cosmic in a way that Walton himself would appreciate, given his penchant for tangenting into universal mysteries during basketball broadcasts. In that same vein, it seems unfair that the cancer that took him at just 71 years old presumably kept Walton from working the final Pac-12 Basketball Championship.

Bill Walton is in Las Vegas last March in spirit, though. I saw dozens of fans walking The Strip that week wearing the tie-dyed Pac-12 logo tee Walton popularized in recent years.

Less about the Pac-12 itself, and more what its demise symbolizes, though, the timing of Bill Walton’s death hits especially hard. Gone is a prominent voice who did indeed use his platform to celebrate education at a time when it’s either ignored due to cynicism, or outright attacked.

As a public advocate for curiosity, for the environment, for the arts, Walton provided a refreshing and increasingly necessary counter to the homogenized and corporatized gruel the masses are fed.

Of all the nonsequiturs Walton slipped into telecasts, the one that most accurately reflects his presence on the public stage came during an Arizona-Colorado game in January 2015. Walton presented ESPN broadcaster partner Dave Pasch — who very much embraced and embellished his role as the company-approved Straight Man — with a copy of Charles Darwin’s On The Origin of Species.

Pasch’s stance on evolution became a running gag between the two, the play-by-play announcer evidently not taking umbrage with it as much as some of Walton’s more vocal critics. While my own belief on evolution in this context aligns far more with Walton’s than Pasch’s, it’s less the content of this segment that encapsulates Walton than it is the sentiment.

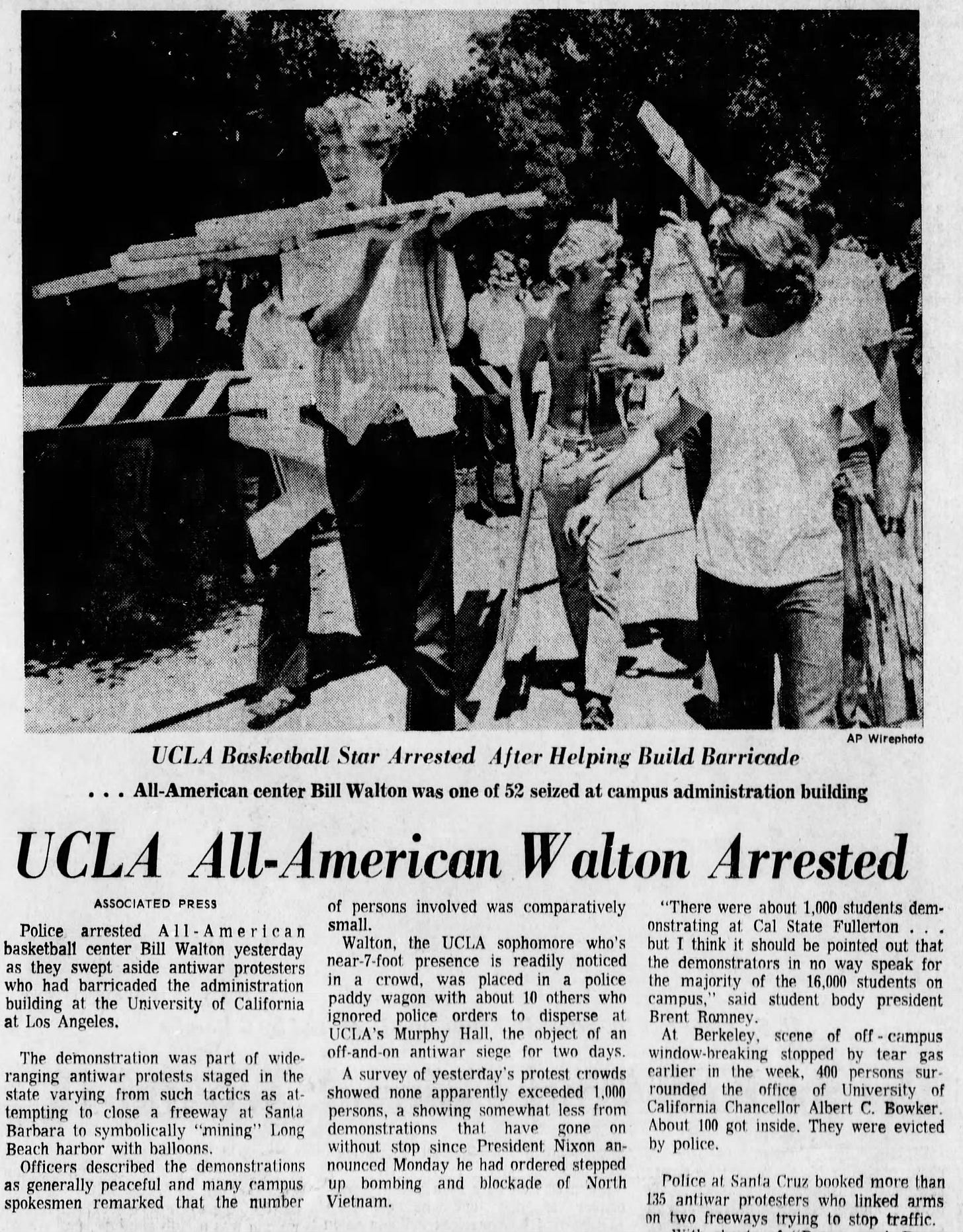

In one regard, Walton never shied away from his expressing his core values for as long as he was in the spotlight. That extends back as far as his UCLA career, when he was far-and-away the best college basketball of his time.

Really, Walton left UCLA at worst the second-greatest college hooper ever.

His 44-point game on 21-of-22 shooting in the 1973 National Championship Game is the single-most dominant performance in the title round ever. And less than a year before that transcendent showing, Walton was arrested for his part in protests against the United States’ continued occupation of Vietnam.

Walton and legendary coach John Wooden reportedly clashed over the star center’s activism. Even so, the two shared mutual respect — in Walton’s case, a genuine reverence.

Up to his very last broadcast, Walton touted the lessons he learned from Wooden, keeping the coach’s legacy alive in a way more significant than the laundry list of on-court accomplishments UCLA achieved under his watch. And, to that end, the second takeaway I glean from Walton’s Darwin moment on ESPN is how Walton embodied evolution himself.

I don’t mean evolution in the sense of Charles Darwin — though his theory applies in that evolving exists to make species stronger, smarter, more capable to handle the rigors of the world. In that regard, evolution applies to us all on a micro level, making us better people through continuous personal change.

Bill Walton evolved on the basketball court in a more frivolous but still meaningful way. When he left UCLA, he was a force of nature on the floor, and that carried into the NBA.

As a Millennial, I really had no concept of Walton’s excellence beyond UCLA having never seen him play. Media made for my generation celebrated certain past greats in a way that piqued my interest and made me actively seek out details on their careers.

Julius Erving’s montage set to “The Greatest Love of All” on the NBA Superstars VHS, for example, validated every Paul Bunyan story of The Doctor’s exploits my dad told me from his time following Erving both in the ABA and NBA.

My impressions of Walton from around the same time were influenced in part reading opinions like that of SLAM, which lambasted Walton’s inclusion on the NBA at 50. It wasn’t until I got a bit older and began to really dig into ‘70s basketball history during my college years that I appreciated Walton’s brief yet impactful time with the Portland Trail Blazers.

NBA TV in the 2000s was an awesome research with its daily replays of classic games. One I vividly watching one summer evening was Game 6 of the 1977 Finals.

Walton, just three years removed from UCLA, was every bit as dominant in the NBA as he was in college. The change he underwent in those few years is most notable in his appearance, as he donned long hair, a headband and either muttonchops or a beard — all major violations of John Wooden’s dress code.

Otherwise, Walton the Player was the same. His 20-point, 23-rebound finale wrapped a season in which he averaged 18.6 points on 52.8 percent shooting, 14.4 rebounds, and 3.2 blocked shots per game en route to winning Defensive Player of the Year and finishing second in MVP balloting.

Walton won MVP the following season averaging 18.9 points, 13.2 rebounds, five assists and 2.5 blocks per game.

That was also the last campaign before Walton faced a series of catastrophic injuries.

A point brought up in the ubiquitous, asinine discussions of all-time greatness that persist in basketball media is that the level of competition has evolved. Certainly there’s truth to it; players are more skilled, more athletic, more everything now than compared to even 20 years ago.

The flipside of that argument, however, is that the world around today’s world evolved to help foster their development. Evolution comes from the need to adapt, after all, and one of the most significant adaptations comes from improved medical care.

Walton essentially missed four straight seasons just as he’d become arguably the best player in the NBA. But Walton’s career is unique compared to others marred by injury in that he adapted — he evolved — with the conditions around him.

The second act of Walton’s NBA career, and the 1985-86 season in particular, is a fascinating case study in evolution not always being about growing stronger so much as thriving with the circumstances available to you.

Sports are full of stories about superstars who can’t move on from being the focal point, which is why instances like Bob McAdoo embracing his role off the bench for the 1980 Lakers, David Robinson becoming a complementary piece to Tim Duncan and Duncan doing the same for Kawhi Leonard are so noteworthy.

In that same regard, Bill Walton’s 1985-86 resonates 40 years later. His numbers are serviceable but hardly impressive in a vacuum: 7.6 points, 6.8 rebounds, 2.1 assists and 1.3 blocks per game.

However, Walton won Sixth Man of the Year and became a catalyst for arguably the greatest Celtics team in the franchise’s illustrious history. His brief but significant tenure in Boston even lives on in pop culture lore, immortalized with a skeleton representing Bill Kreutzmann wearing Walton’s warmup jacket in the only music video Grateful Dead ever produced.

Still, Walton’s time in the NBA can be as contentious as the issues he brought during Pac-12 basketball broadcasts. Just a few months ago, Rasheed Wallace went on a podcast diatribe in which he denigrated Walton’s career and touted Maurice Lucas as the better Trail Blazer in the late ‘70s.

Walton and Wallace also have their own history, stemming from the former’s time as a commentator overlapping with Sheed’s NBA career. To this end, Walton’s presence on college basketball broadcasts for the last decade or so demonstrates personal evolution.

It may seem hard to believe now, but in the ‘90s, Walton was a cantankerous color commentator who offered dismissive analysis of modern players; proto-hot takes, if you will. There’s a reason players of that generation like Wallace and Shaquille O’Neal specifically are negative about Walton’s own presence.

What Walton’s transformation behind the microphone signals is that one can hold the same convictions they had in their youth but still change. Maturity doesn’t come from abandoning past values, but in finding common ground with others more often; for making conditions more adaptable for those who follow you.