Little League

My oldest child completed his first Little League season a week ago. Playing in the machine-pitch league that bridges the gap between Tee Ball and true baseball, his skills improved dramatically over the course of the season; he discovered a love for the game; and, most importantly, he made new friends.

Little League in our neighborhood is a community event akin to a block party. Parents and siblings set up their folding chairs around the fields, had pizzas delivered, and a few of the more…intrepid parents brought coolers of mystery beverages. No matter how long my son continues to play baseball, this first introductory spring will always hold a particularly special place in my heart.

Moments like these make parenting the most fulfilling experience of my life, even amid the inevitable trying circumstances.

But while challenges in parenting are inevitable, and usually daily, no parent should have to accept sending their child off to school in the morning for them never to return because of gun violence.

It’s unacceptable and inexcusable, and yet it continues with both tacit acceptance and myriad excuses as to why it doesn’t just keep happening, but becomes more commonplace.

My wife and I sat our oldest son to talk about the murders committed in Uvalde, Texas, and I assuaged both his and my fears with an inscrutable fact: Mass shootings are outliers. There are thousands of schools nationwide, and tragedies such as the killing of 21 at Robb Elementary School are rare.

But these are human beings, not data points on a spreadsheet. The outliers shouldn’t exist, certainly not in the numbers that have become too normal in the last 15-20 years.

I was in high school in April 1999 when gunmen killed 13 classmates at Columbine. Following news of the massacre chilled me, not just because this happened to kids my own age but because of the sheer mayhem of it all.

This wasn’t something that happened with any regularity. Not then, anyway.

Columbine High’s run to the Colorado State Championship in football just a few months later made national news, and deservedly so. The Rebels lived up to the moniker, rebellion against the terror Klebold and Harris sought to install on the school.

The memories of following Columbine’s gridiron resurgence, a fairy-tale chapter within a larger declaration that our society wouldn’t forget nor allow it to happen again, are more bitter than sweet.

Our society’s failed the Columbine survivors, who are now parents in their own right. We’ve failed the parents and survivors of Sandy Hook, and of Virginia Tech, and of Stoneman Douglas — mass shootings that all occurred since the expiration of The Public Safety and Recreational Firearms Use Protection Act in 2004.

Per U.S. News & World Report, there have been 13 mass shootings at schools since Columbine, each of which have been since 2005.

That doesn’t include tragedies like the Buffalo grocery store white supremacist murders, and that only accounts for school shootings with a defined metric of at least four killed. I was a student at the University of Arizona in fall 2002 when a nursing school student opened fire on professors, causing widespread panic on campus and killing three — below the defined term for a mass shooting.

But again, those three faculty members killed were people, not statistics. One such murder is one too many.

In the same vein as the ‘99 Columbine football team, I think of Utah’s run to this past season’s Rose Bowl and the Moment of Loudness. Rather than ask fans to observe silence for Aaron Lowe and Ty Jordan, Kyle Whittingham implores supporters to cheer in recognition of their lives — lives taken by gun violence.

The message in the Moment of Loudness asks us all to smile and embrace one another through the community bond sports give us.

But in using our voice, it’s most important to do so to speak out and force changes. Not ask for change — demand change that addresses not only the high-profile, mass shootings in places like Uvalde but the isolated killings like those of Lowe and Jordan, or the often-cited but rarely genuinely cared-about shootings in Chicago.

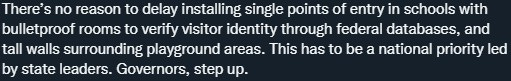

Among the more common deflections dressed as action been floated in the aftermath of Robb is encapsulated in the following. I cropped the author of the tweet because that’s irrelevant to the point I want to make.

I don’t know the ironclad solution, but I do know a scenario that turns schools — a place meant to be joyful for students — into maximum-security prisons is no solution at all.

In the wake of 9/11 more than 20 years ago, we were told that cutting ourselves off from enjoying our lives was giving into terrorism. Former Heisman Trophy winner Robert Griffin III said it best when he placed the same label on these shootings.

Sacrificing the community built through our schools, churches, perhaps even our Little League games is not an option. Neither is the continued failure of the parents and survivors impacted by gun violence, past and future.