From The Archives: The Strange Story of The Bowl Game That Shouldn't Have Been

The following appeared on Patreon in December 2020:

The city was wiped out as a target as soon as the bomb hit — probably all industrial targets were vaporized by the blast. We could see fires on both sides of Nagasaki harbor. We felt more of a blast than we did at Hiroshima. — Major Charles W. Sweeney, speaking to the United Press services on Aug. 10, 1945

Mr. [Shigemitsu] Tanaka, almost 5 years old when the bomb fell, was playing under a persimmon tree on Aug. 9, 1945, when he heard a huge thunderclap and the sky went completely white. All the windows in his family’s home were blown out.

His mother went to work at a local elementary school where survivors were taken for medical treatment. There, Mr. Tanaka heard moans and smelled the stench of burning flesh. Mr. Tanaka’s parents suffered from repeated illnesses throughout their lives. His father died from liver cancer 12 years after the bombing. — From a 2016 New York Times collection of atomic bomb survivors' memories

* * *

Less than five months after Pres. Harry Truman oversaw the use of the first — and, by the grace of God, only — atomic weapons ever deployed in combat, Hiroshima and Nagasaki remained ravaged without relief in sight.

The Associated Press reported on Jan. 1, 1946, that Hiroshima mayor Shuchiro Kihara requested American assistance in the rebuilding effort. "Japan can furnish the labor," the AP report of Kihara's meeting with American reporters said, "But America should provide materials, food, clothing and medicines."

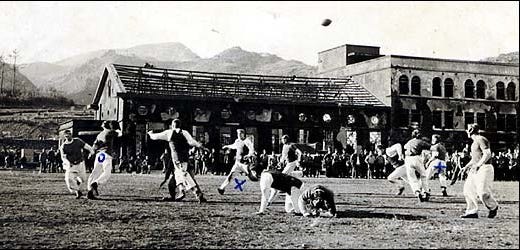

That same day — New Year's Day, 1946 — football teams lined up on a makeshift playing field amid wreckage in Nagasaki for the first and last Atom Bowl.

* * *

Around the time English migrants established the Jamestown settlement in present-day Virginia, Japan instituted a policy of isolationism that lasted two centuries. From the 1600s into the mid-1850s, the nation's primary port for the limited trading partners with which it did business was in Nagasaki.

Almost a century before Fat Man fell on the port city, Nagasaki was cite of a bloodless conflict involving the United States.

At the behest of Pres. Millard Fillmore in 1853, Matthew Perry led an expedition of Naval ships to Japan. Their presence was intended to send a clear message. From a 1972 New York Times piece on the Fillmore Society's annual celebration of the 13th president:

It was Millard Fillmore who launched Japan into the modern age by remote control. He sent Commodore Perry on the gunboat mission across the Pacific to force the Japanese to end their centuries of isolation and sign a treaty.

Diplomacy, it wasn't. In the same century that Manifest Destiny came to completion, the same motivations that expanded America from one end of the content to the other sent the nation's military to the other side of the globe.

For Perry, it was the desire to convert the "savages" of Japan to Christianity. For America's leaders, the island nation was viewed as an essential new frontier in a changing world.

A year after Perry's "Black Ships" landed at Edo, Russian ships came to Nagasaki. Japan's age of isolationism was officially over.

With forced opening to the rest of the world, Japan joined the Industrial Revolution; went to war with Russia at the turn of the century; and experienced unprecedented cultural change. Foreign nationals were able to live in Japan in larger numbers, and brought with them ideologies and concepts from their home countries.

One such foreign national, Louisville native and Christian missionary Paul Rusch, introduced America's version of football to Japan in the early half of the 1900s. Rusch is credited for overseeing the first official games in 1934. In 1941, the Kansai Collegiate American Football League played its inaugural season.

The league remains active to this day, having just last week completed a COVID-19-modified season with the 75th edition of the Koshein Bowl, Japan's national championship game.

The inaugural Koshein Bowl kicked off in 1947, the same year as the Citrus Bowl; one year after the Atom Bowl; and less than two years after Fat Man and Little Boy forever changed the course of humanity.

* * *

The 20th Century, and especially the first half of the 20th Century, was truly the age of baseball as America's pastime. However, college football's popularity exploded in the 1900s and only grew in the 1920s thanks to influential journalists like Grantland Rice making stars of players such as "The Galloping Ghost" Red Grange and Notre Dame's Four Horsemen.

More so than Major League Baseball, college football was America's Game during World War II in that the athletes playing stateside were the same age as many of the boys fighting in Europe and the Pacific.

In some noteworthy instances, star college football players were the soldiers and sailors and airmen in combat. Lars Anderson's The All-Americans on the 1941 Army-Navy Game and Brian Curtis' Fields of Battle on the 1942 Rose Bowl Game are must-reads that detail a few of these stories.

Indeed, landmark moments and teams, like the Army West Point dynasty, are deservedly among the game's most celebrated. The Atom Bowl does not rank among the fondly remembered milestones — and just as deservedly.

* * *

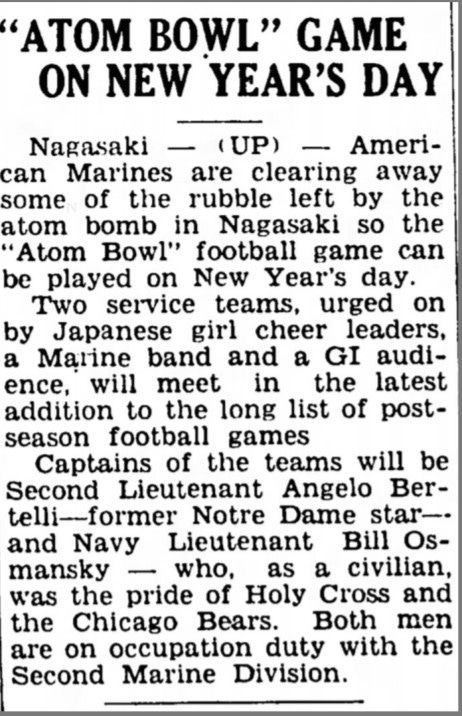

The Atom Bowl exists as one of those things that presumably seemed like a much better idea in concept than in execution. Below is the United Press wire report announcing plans for the game, published on Dec. 29, 1945:

The UP's misspelling of "Bullet" Bill Osmanski's name notwithstanding, that's an impressive pair of headliners. Of the aforementioned star players who shaped the wartime era of college football, Angelo Bertelli stands out for winning the 1943 Heisman Trophy then putting a pro career on hold to serve in the Pacific.

"When you talk about the history and tradition of Notre Dame football, one of the central figures always has been Angelo Bertelli," former Notre Dame executive vice president Rev. E. William Beauchamp said upon Bertelli's death in 1999.

Osmanski is a similarly important figure in the history of Holy Cross, leading the Crusaders to a 23-3-3 mark over three years of a College Football Hall of Fame career. Osmanski earned All-Americans in both 1937 and 1938, then in 1940, starred on an NFL championship-winning Chicago Bears team coached by George Halas. Like Osmanski, Halas played in another noteworthy wartime game, starring for the Great Lakes Navy Bluejackets in the 1919 Rose Bowl — but that's a story for another time.

So with a very recent Heisman winner on one side, known for his revolutionary style of play -- the "Springfield Rifle" Bertelli was among the more prolific passers of the era -- and a two-time All-American/NFL All-Pro and champion, the Atom Bowl had the star power to make for an interesting contest.

What's more, the concept of a goodwill exhibition makes sense. For the players and servicemembers stationed in Japan, a Jan. 1 contest provided some normalcy. To ring in the New Year with a marquee football matchup brought an American flavor to the land of a new ally (one gained by force, but an ally all the same).

In theory, the same principle of normalcy could be posited for the Japanese. The war put the Kansai League on hiatus after just its first season, and because the war was fought primarily close to home in the Pacific, there was no equivalent to Army West Point to grow into a powerhouse as a result of its enlisted numbers.

While the idea of the Atom Bowl may have been celebratory, reality was anything but.

Writer W.W. Watt was on the scene in Nagaski in 1946. He shared the details from his notebook in The New York Times in 1984. The entire article is a worthwhile, if not necessary read, but I've included a few especially pertinent passages.

First, while a pair of bonafide stars headlined the Atom Bowl -- and played well, with Bertelli throwing two touchdowns and Osmanski rushing for one -- the football itself wasn't football.

Bertelli told the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph in April of that year that as coach of the Navy team, he agreed to a tie with Osmanski's Marine squad despite Bertelli having the more talented roster. It ended 14-13 for the Marines, though, when Osmanski attempted to shank a PAT only for the kick to go through the uprights.

The innocuous attempt at point fixing wasn't what rendered the Atom Bowl only a facsimile of football, however. The game's namesake, the unprecedented killing machine dropped on the city five months prior, was responsible. Watt's essay from The Times explains:

On the day of the game, the Atomic Area - two miles from North to South and seven-tenths of a mile from East to West - was a desert of devastation. There was ample terrain for football, but because of the sharp edges of shattered bricks and plaster, fused glass and other shards, it was considered the better part of valor to play touch instead of tackle.

Hiroshima's pleads for assistance being published the same day that Nagasaki staged a football game is instructive. Nagasaki was no better off -- and in fact, was in worse shape.

Nagasaki sits in a valley, which condensed the bomb's impact more so than the first weapon dropped on Hiroshima. This meant more concentrated devastation, and devastation that may not have been intended even within the stomach-turning context of using the bombs at all.

Another book recommendation, David McCullough's biography Truman, is a rich resource of details of the bombings, from the perspective of the man who history most associates with them. For the sake of this essay, read this New Yorker piece from the 70th anniversary of the attacks. Among the key points: Nagasaki was not among the intended target cities.

From Watts' Times essay is a harrowing story, recounted from one of the few locals taking in the Atom Bowl, who responded to the author's attempts to teach the game.

I tried to explain, in a fatherly way, the elementary principles of touch football, what a bowl game was, and why Americans celebrated New Year's Day by worshiping a collegiate sport that normally was played between September and November. But Morii was in no mood or condition for serious discourse.

Then suddenly out of the dust it came to me - something he had told me on our first meeting in November. He had, he said, an ailing wife at home, but no children. His boy and girl had been killed on the morning of the bomb, crushed against a wall by the force of the blast.

There is nothing to extrapolate, no modern-day metaphor to extract from the one and only Atom Bowl. Its history is worth remembering, however.

Coaches and media love using football as a conduit through which to reflect our most admirable traits as a culture: teamwork, self-discipline, physicality, courage. The game, in this instance, also provides a snapshot of war's toll, and specifically, the grim reality of the atomic bomb.